"A Peace of Us" - the OU collection exploring why Good Friday Agreement matters 25 yars on

This arcicle is part of "A Peace of Us", our special collection of resources exploring why the Good Friday Agreement is relevant to our lives 25 years since its signing.

The Peace Dividend - and its interpretations

2023 will bring much political reflection to the North of Ireland. It is easy in this 25th anniversary year of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) for this reflection to assume the form of platitudes, focusing on the contributions of venerated peacemakers to our society. These contributions ought to be celebrated, given that the fragile peace secured by leaders in 1998 has underwritten much of the social progress that has since been achieved in this state. In the fog of misty-eyed reflection, however, there is a danger that this progress can be overstated.

The absence of state and paramilitary violence is of course a precondition for lasting peace and reconciliation and remains the most significant reason why the Good Friday Agreement matters. However, the economic foundations of this peace, the structure of the economy in the North and who benefits from the spoils of economic activity, are fundamentally unsustainable in social and environmental terms.

It would be unfair to retrospectively place the responsibility for economic transformation at feet of negotiators. But it was actively hoped that a ‘peace dividend’ might flow from the agreement, improving living standards and undermining a cause of social unrest. This ‘dividend’, it was believed and few in power here have wavered from this belief since, must be delivered by flows of foreign capital to the North, increasing GDP growth and making us all a great deal richer.

Why the Good Friday Agreement should benefit more than the GDP

To that end, the economy in Northern Ireland has doubled in gross terms (measured in GDP) since the Good Friday Agreement. It must be asked, so what? Have mental health services for traumatised survivors of the Troubles expanded at the same rate? Have public transport routes to isolated rural areas, or social housing provision in our cities, also doubled? They have not. Moreover, wages remain low here, and in many public and private sectors they have remained stagnant or in a state of real decline for the decade following the global financial crises and the Great Recession post-2008.

25 years on, therefore, it is time to ask seriously, to whom has a peace dividend accrued? Because of, and not in spite of, a strategy rooted in a reliance on Foreign Direct Investment over the last two decades, the North remains an economy blighted by inequality, low pay, and vast regional disparities. International capital arrives in South Belfast, for example, and not in Crossmaglen or Carrickfergus.

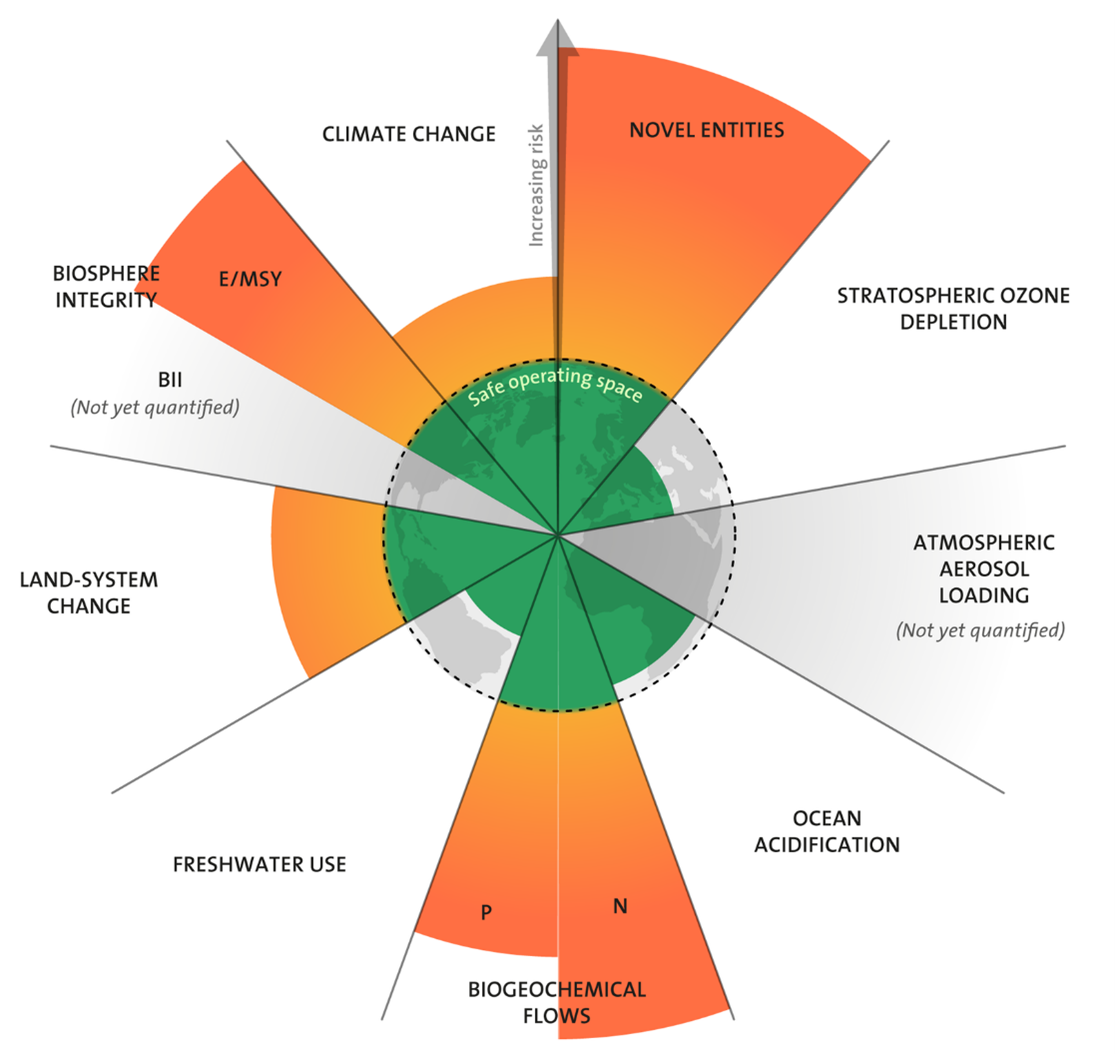

This approach to economic development is not only evidentially flawed in creating lasting improvements, in an equitable way, in people’s wellbeing or material living standards, it is also a growth regime that has breached our planetary boundaries, as the world economy has generally. In an era of ecological crises, the least that is demanded from us is that we shape economies in a way that respects the real, non-negotiable restraints of the earth (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Breaching our planetary boundaries. Source: Steffen et al, 2015This is not merely a story about carbon emissions (the driver of the greenhouse effect, and therefore global heating), but about all the ways in which our economy interacts with the earth, it extracts and transforms energy and matter to produce the things we need (and, more unsustainably, want). The earth can only sustainably reproduce about 7 tonnes of material per person per year – the Northern Ireland economy consumes more than twice that (16.6 tonnes per person). Over 90% of this material is freshly extracted from the earth and will not be reused.

Energy consumption continues to rise, and the rapid pace of renewable energy transition in the 2000s and early 2010s has slowed significantly in the absence of adequate government support or initiative. Greenhouse gas emissions have fallen significantly since 1990 but continue to rise in agriculture (by some measure the largest emitter in the North), and frequently in transport.

The way forward: why the Good Friday Agreement can become a bigger promise

Fortunately, the antidote to the two main strands of unsustainability identified here is an embrace of the good life. Warmer homes for all means less energy consumption and lower energy bills. A mass public investment program in public transport and clean energy can transform rural communities. A just transition to forms of work which respect the fragility and power of nature can create better-paid green jobs for all.

If we want a fairer and greener society, then we must set specific objectives to achieve this. It means jettisoning fairytale ideas of endless economic growth, and considering the data which tells us both our society and the natural world which underpins life on earth are ill-served by this objective.

A public deference to private capital will only intensify a model that has consigned many working-class communities in the North to isolation. For areas still blighted by paramilitarism, prescription drug epidemics, poverty, lack of access to basic services, and no prospect of secure and well-paid employment, a handful of glassy office buildings in South Belfast will do nothing. Shaping an economy which serves these communities above all else, and which rises from the bended knee stance to US multinationals, is more socially desirable and, crucially, ecologically sustainable.

It should not be mistaken that the scale of transition required to achieve this and do our part to prevent the collapse of the earth’s life supporting systems will require political and economic transformation which may dwarf the titanic achievement of Good Friday in 1998. It will require political will of equal stature, and, crucially, mass mobilisation from civic society to demand nothing less.

The legacy of why the Good Friday Agreement matters is complicated, on the whole positive, but by no means perfect. Our transition to lasting and sustainable peace will not go further without an economy which refuses to neglect and abandon communities in the name of growth. If this is what we desire, then it must be what we must demand.

Find out more

To discover why the Good Friday Agreement matters in a wider context, why not try the courses below?

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews