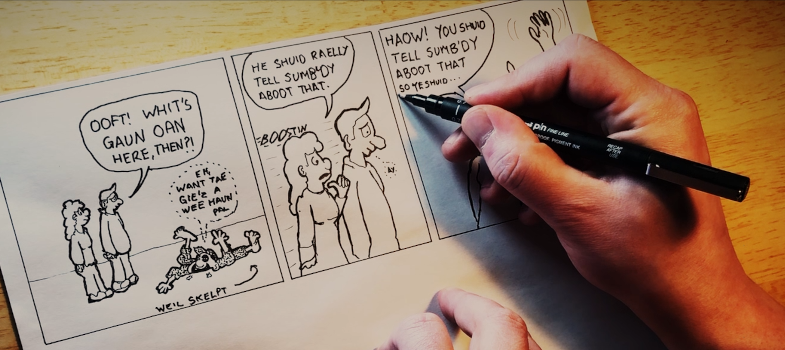

Scots as a language learning option in schools

© Michael Dempster

3. Tutorial

Activity 8

As in previous units, the tutorial is designed to provide a space for the discussion of key questions from the unit with your peers, to share ideas you developed when studying the unit input section and to start planning your application task.

In the tutorial your own assumptions and experiences will play an important role and the discussion will build on Higgins and Ponte’s (2017) finding that ‘the teachers’’ own linguistic histories strongly shaped their views about multilingualism in schools, [and] that a formally sanctioned opportunity to experiment with multilingual pedagogies opened up new spaces for critical self-reflection about the links among languages, teachers’ identities, and academic engagement for multilingual learners’ (p. 15).

A.

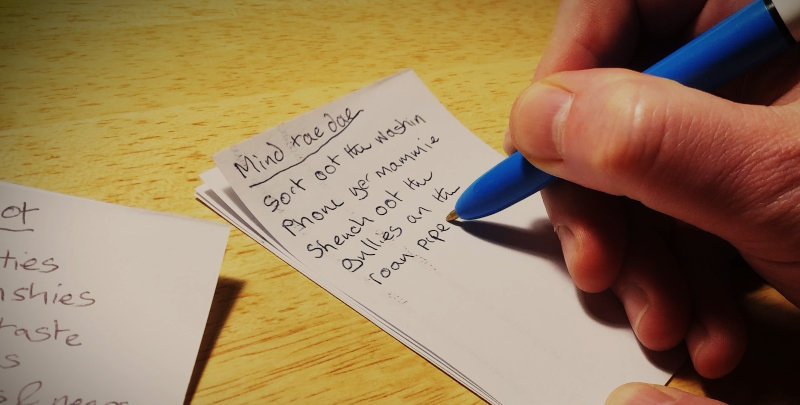

Go through your notes from Activities 1 to 7 and select key thoughts you noted down about:

-

teaching Scots as a subject in its own right in Scottish schools,

-

teacher confidence in using, teaching and assessing Scots in the classroom,

-

important steps that need to be taken to build pupil confidence in using Scots in the classroom and developing their Scots literacies.

Bring these to the tutorial for discussion.

B.

Closely related to the approach of teaching Scots as a subject in its own right, is another concept, namely that of Scots being a crucial aspect of multilingual practices in the classroom in Scottish schools.

Read our summary of research on multilingual classroom practices and take notes to bring to the tutorial discussion of:

-

important findings from the research mentioned here,

-

your own thoughts related to this about your and maybe also your colleagues’ teaching practice and context,

-

the role of Scots alongside other languages pupils bring to the classroom – can Scots lead the way here for the embedding of multilingual classroom practices?

Multilingual classroom practices – pros and cons

Moore and Vallejo (2018) highlight reasons why multilingualism has been mostly absent in our classrooms:

‘A large body of research has demonstrated that the plurilingualisms and pluriliteracies that children and youth bring to classrooms are often not those required for school success. This is even more so for students from underprivileged backgrounds, a demographic where children and youth with family backgrounds of immigration are over-represented. [...] Thus, paradoxically, students who are ‘pre-equipped’ with diverse communicative repertoires that could be used to the benefit of their education, and of society, are often vulnerable to poor school results’ (p. 25).

Contrasting that, there is a growing body of research investigating the benefits of bringing multilingual practices to the classroom. Findings from such research show how important it is to incorporate home languages in the classroom to activate prior knowledge. In his article ‘Why mixing languages can improve students’ academic performance’ Rasman (2021) identifies three key advantages of utilising pupils’ multilingual skills in the classroom:

-

‘multilingual skills help students to activate their prior knowledge, which positively affects the process of understanding new knowledge: Direct and indirect effects of multilingualism on novel language learning: An integrative review

-

multilingual skills help build rapport between students and teachers, which is important for improving academic performance;

-

multilingual skills help increase students’ well-being, which is a key factor in successful learning.’

Lompart (2022) in a recent ground-breaking edited volume on plurilingualism in education, reports findings from a collaborative plurilingual classroom project where teachers and pupils learn with and from each other:

‘All in all, the analysis of the data has shown how by positioning students as participants and as experts in their languages, Urdu, in this case, the traditional knowledge asymmetry associated with classroom talk is changed and the youth can take up roles as experts and thus direct the teaching activity and introduce metalinguistic reflections. Actually, the adult’s admission of her lack of competence in the Urdu language […] accounts for the youth’s participation and transformation into teachers and experts. (p. 63)’

Lompart concludes that plurilingual practices in the classroom ‘subvert the traditional class dynamic […] by giving value to the students’ plurilingual repertoire and by situating them as full participants and agents in their process of learning. [… The lesson design] set out from the crucial idea of understanding that the students are experts in their respective languages and that their knowledge is valid for academic work. (p. 63)’

Wagner’s (2021) investigation into teacher practices that can support multilingual learners highlights the role of the teacher modelling in building learner confidence and challenging their own assumptions about classroom language use. He emphasises that ‘nurturing multilingualism starts with creating spaces in which students are comfortable and empowered to use all of their languages. Doing this required making the use of multiple and non-English languages routine and using them in ways that had meaning and significance in the classroom’ (p. 6). An important finding from Wagner’s research, that has often been debated in the context of teaching Scots, is teacher proficiency:

‘For teachers, stoking language curiosity in children did not require being proficient in the languages their students spoke. […] In many of these examples, supporting students’ curiosity required both questioning and moving past teachers’ own assumptions and preferences about how to use language, an obstacle that […] can limit teachers’ use and encouragement of multilingualism in the classroom. A willingness to move beyond their own comfort zone was part of how these teachers were able to see, recognize, and encourage the language practices that excited and motivated their students’ (p. 9).

Coming back to literacy development in multilingual settings, in our case writing in Scots, Wagner (2021) underlines that allowing multilingual outputs is an important building block for pupil confidence and development in all the languages they are using. He states: ‘[W]hen writing, […] teacher encouragement to make active choices led some children to produce multilingual texts. Across classrooms, teachers shared similar stories about how the “decision to allow students to choose their language preference […] made learning more fun and comfortable for them” (Teacher 4, Interview)’ (p.10).

C.

As the final step to prepare for the tutorial, you are going to engage with an impactful school-university research partnership between Banff Academy and The Elphinstone Institute at Aberdeen University that investigated the influence of teaching Scots on pupils' self-esteem and wider achievement, using Participatory Action Research and creative arts to explore attitudes to Scots in school.

Watch the presentation by the two primary investigators, PhD student Claire Needler and teacher Jamie Fairbairn, at the FRLSU conference 2021. (Note: should you be asked for a password, please use: FRLSU_202!)

*Please note: You can watch this video with

subtitles/closed captions by activating this feature on the YouTube player

When watching the presentation take a note of findings from the partnership on one or more of the following:

-

the approach and methodology that was used in the project,

-

how the project created spaces where ‘critical questioning of the world’ was possible,

-

how positive attitudinal change and encouraging the pupils to view the Scots language as a valuable part of both their cultural heritage was achieved,

-

the role the creative arts played in this process,

-

how the project aims (fostering inclusion, developing literacy, boosting cultural knowledge and inter-generational communication) were achieved.