Transcript Linda Bruce presentation: Whit (we hink) we ken aboot Scots

My name's Linda Bruce and I'm a postgraduate researcher at the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics, and I'm working on a PhD project investigating language ideologies and identities of new speakers of Scots.

Today I'm going to give a short presentation entitled what we think we ken about Scots language ideologies and minoritised languages.

So, I'll cover these areas. First of all, a brief introduction to the concept of language ideologies, some language ideologies about Scots and Scotland.

I look at who speaks Scots in Scotland and why they do or don't.

And finally, some thoughts about how we can recognise potentially negative language ideologies and maybe think about addressing and challenging them.

Let's begin with the definition of language ideologies and sets of beliefs about language articulated by users as a rationalisation or justification or perceived language structure and use.

I like this definition because it highlights the links between language ideologies and language structure and use. Ideology is seen by many academics as a bridge between what we believe and what we see and do in terms of language.

So, these beliefs about language are not just abstract ideas, but they actually affect practically every language choice that we make.

We might think of ideologies or not think of ideologies as set, unchanging in the background. But we're reminded here with this quote that just as they're not abstract, language ideologies are not fixed, although one of the interesting and the most fundamental things about them is that they often represent themselves as fixed, immovable, natural, age-old, historical or just common sets of beliefs about language and are unquestioned.

So in other words, as an idea about language is presented as a fact and repeated and reworked over and over. It becomes as taken for granted and seemingly unchangeable.

So, in other words, one of the essential features of ideologies is that they work at an unconscious level. It seems implausible that people should adhere to an ideology or recognising it as such.

So now let's see if we can attempt the implausible and try to recognise some ideologies about languages in Scotland, specifically regarding Scots.

Take a moment to think about what you believe about Scots.

You might want to think about, for example, a definition of Scots and how it relates to English in Scotland, the status of Scots in Scotland, what kind of language policies especially, for example in education, you know about regarding Scots in Scotland.

Maybe anybody you know who speaks or uses Scots? Who are they? How do they use Scots and in what contexts?

So here are some views about Scots that researchers have encountered.

Maybe you thought of one or two similar ideologies.

For example, Scots is a language, Scots is Gaelic, Scots is a dialect of English, Scots is just how some people speak, Scots was a language, but isn't now, Scots was invented by the SNP for political reasons, Scots is spoken by old folk in the countryside, Scots should only be spoken by Scottish people. So, these are the some of the things that some people might believe about Scots.

OK, so according to researcher Van Roy, there are three common factors that affect what is believed about languages, language and languages.

Coming from the point of view of the Western world within which we're situated, so these include a linguistic variety’s constructed relationship with another in the same region.

The official status of a variety within a nation.

Nation state and language and educational policies applying in that nation state. These factors form these powerful language ideologies of modern nation state were profoundly influenced by the way they're labelled and perceived by society, and then as the quote earlier from Silverstein suggested, these beliefs actually affect language structure and use, like: How much? How often? And where we use particular languages, and particular forms of languages.

So let's go on to briefly investigate each of these three factors with regard to Scots.

First of all, Scots and its relationship with English in Scotland.

So, you might have seen something like this, a language tree showing language branches of families.

This raises the question is Scots a language, and if so, where does it come from and how does it work? What's it like? What's it different to? What's it not like?

Here's a closer look in case you didn't spot Scots initially.

And some people talk about definitions of languages and relationships between language varieties in terms of how alike they sound, or in linguistic terms, how much mutual intelligibility there is.

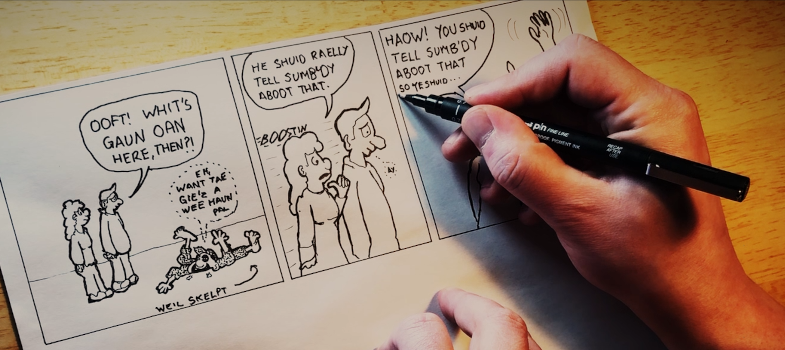

So, let's see how Scots rates with mutual intelligibility for you. If you click on the speaker on the slide, you'll hear a reading from the Scott's New Testament.

How much can you understand in the first listening?

You've probably noticed that Scots here is positioned right underneath the massive English branch of the tree. Well, yes, we know that Scots is a West Germanic language and closely related coming from Northumbrian English from the 13th century onwards, and that far fewer people speaking it than English globally. It's also good to remember that this sort of family tree image of languages in itself reflects certain constructed relationships and hierarchies that are actually ideological and actually reasonably recent.

Thomas Bonfiglio traces back these sorts of representations of language related to the natural world, trees, genealogy, families, maternity. If you think of the expression mother tongue, as ideas that originated in the 18th and 19th century.

So, it reminds us again that these are ideologies and that they tend to reinforce ethno-linguistic and nationalist prejudices, or in short beliefs that language equals race equals nation.

So, in other words, we should try to remember to never let constructions of language and tradition masquerade as cartographies of the real.

So, in an effort to try to establish what the real might be, it might be useful to consider how some recent and not so recent research on Scots considers the constructed relationship between English and Scots in Scotland.

So, around the end of the 20th century there's more socio-linguistic and academic interest in Scots.

A bipolar continuum idea was suggested as a representation of this constructed relationship between Scots and English in Scotland, with Scots and Scottish Standard English opposite poles of a line along which speakers shift according to function register or for style purposes.

This model was based on the influential work of Aiken et al from the 1970s and 80s.

There was also suggested here a class dimension associating the middle and upper classes with Scottish Standard English and Scots with working class.

This was ideological as well.

So, this is an example of how the bipolar continuum might work, with speakers choosing a place on the line depending on their linguistic repertoire, knowledge, class, maybe preferences, and the speaking situation. Again, all of these are influenced by and constitute complex and changing language ideologies.

The closest to Scottish Standard English, comprising Standard English, mostly with the Scottish accent and the most Scots option featuring Scots phonology, vocabulary and syntax, and you can see those reflected in those example sentences there.

However, socio-linguistics has more recently moved away from focusing mainly on class as the key motivator behind language choice and use just as a result of the way that society has changed and the effects of globalisation.

The bipolar continuum model is more recently conceived as a multidimensional socio-linguistic variation space by Warren McGuire, we're speakers, speakers select more or less Scots forms and the same as we did in the bipolar continuum with the purpose of indexing not just class, but a much broader range of social meanings which might or might not be associated with Scots or English.

So, they might choose a particular way of saying something to show that they are in Scotland but not England, that they are working class or that they are educated, or that they are local or they are Glasgow and not Edinburgh, that they are cool and they are different, that they are old fashioned, that they are Catholic. Lots and lots of meaning attached to the choice.

So, for example, we look at someone making a choice to say they're Glasgow and not Edinburgh. They may use the word weans to describe children, but someone in Edinburgh might use the word bairns to show that they're Edinburgh.

There are lots of things like that in Scots.

OK. The second factor in creating language ideology is if we go back to Van Roy's three factors is that variety's official status.

This is an interesting one because to be clear, Scotland currently has no legal official language, although English is de facto the official language of the country.

But this is set to change, so just a few weeks ago the Scottish Government introduced the Scottish languages bill, which is the first piece of major legislation regarding languages in Scotland for almost 20 years.

And as we can see here, the first point of the Scots section of the draught bill gives official status to Scots within Scotland.

However, when we look down to part four, it becomes a little more tricky. The Scots language as used in Scotland, is the definition of what Scots language is. So, as I've suggested earlier on, it's not necessarily something that could be easily delineated from other forms used in Scotland.

Does this mean anything written in Scots? Does it mean any spoken Scots? And if so, given how Scots works in Scotland in this sort of variation space with Scottish Standard English, how much Scots is enough to be officially considered to be Scots?

I don't really have the answer to those questions, but I would say that it is a positive step to attribute official status to Scots in Scotland and certainly a move in the right direction in terms of raising awareness of the fact that Scots is a language and also raising its prestige.

So, if you want to read the bill or to find out more about it, you can go to the Scottish Parliament website and find it there with an update of how it's progressing.

Now the third area that contributes to what we think we know about the language is state policy concerning languages and education.

So, as I've said on the one hand, Scots is soon to be an official language in Scotland. It's also protected with language status in the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages which affords its certain protections and official support.

The Scottish language policy was published first by the Scottish Government in 2015, and it will now be updated and strengthened into a Scots language strategy as part of the new Scottish languages bill.

The other side of this policy coin is Scots in education in Scotland.

This is in another area where ideas about language originating many, many years ago have had a lasting effect on what we think about Scots.

When compulsory, universal education was introduced to Scotland in 1872, both Scots and Gaelic were simply excluded from classrooms.

The suppression or separation of indigenous languages from education systems is a familiar scenario across the world, of course.

And stories of children being punished and berated for the use of indigenous languages are really common, especially in the colonial context.

So for at least 150 years, Scots was considered wholly inappropriate for use in education.

However, it's being slowly introduced and accepted as part of the Scottish school curriculum these days.

Thanks to the 2012 introduction of the 1 + 2 approach to learning languages, this allows for Scots as an optional additional language taught from age 9.

And so overall, in recent years, it seems that in part thanks to grassroots movements among some really Scots-aware teachers who were ahead of and went further than the 1 + 2 approach it's become much more acceptable for teachers to include, much more welcome for teachers to include Scots in the classroom, especially for younger pupils, for whom it's a significant variety in their home or their community.

However, even though the number of Scottish schools offering Scots language teaching almost doubled from 59 in 2018 to 100 in 2023, and the number of students achieving the Scots Language Award increased from 100 to 418 in just one recent year, Scots is still neither a standalone nor compulsory subject as a language.

As you probably know, I'd also mention that Scots language teacher training has not really been widely available nor mandatory, so the teaching of Scots, which has sometimes been excellent, has also sometimes been patchy and ineffective.

The Open University has made progress in this area recently, launching the dedicated Scots language CPD programme from teachers.

A lot more can be done. We haven't even considered higher education yet.

No undergraduate degree in Scots language exists in any Scottish university at the moment.

And returning to new speakers, that's adults looking to learn some Scots, the participants that I'm researching, they don't happen to have access to a family member willing and able to teach it.

The resources available for them to learn Scots, certainly in a formal way, are pretty minimal.

So, to return to the discourse around language and educational policies, it's fair to say that Scots is still very much presented ideologically as optional, extra, additional, nice to have for children being schooled in Scotland.

If you're a university student or an adult learner, it's almost invisible.

This ideology still tells us that English is best, the one that will get children ahead in education and career.

And these beliefs reflect an emphatically monolingual one Nation, one language, ideology towards languages, which exist in Great Britain and the United States. Unfortunately, we don't seem to be able to shake off this monolingual orientation.

So, I've provided a few thoughts about how what we think we know about Scots is and has been constructed by the nation States and reflected in widespread beliefs about minority minorities, language in general.

I'd like to finish off by considering new speakers of Scots, so that's adult learners. That's the group that I'm working with.

Adults who didn't grow up with Scots, who make a conscious decision to learn and use it, how they experience and sometimes perpetuate language ideologies like the ones we've talked about.

So, here's one of my research participants talking about the official status of Scots, its relationship to other language varieties, and importance to them of language or dialect as a label in terms of language ideologies.

So in this example we can see the participant manifesting this ideology very, very clearly, if you click on the speaker, you'll be able to hear what's transcribed here.

So, for this person, how linguistic variety is named is seems really important.

The desire, to use of the label language over dialect and that is a way for them to kind of align themselves as the identity of someone who's invested in social justice through and beyond language use.

And he acknowledges that he's siding with the minoritized or disadvantaged group by calling Scots a language.

And using that term themselves and they also refer here to both the constructed status of Scots in the UK, in the UK and Europe, and comparing it with other varieties there as well as directly to the official status or lack of of Scots.

So, both of those were strong factors in the linguistic ideologies that I highlighted earlier.

So, in this account she talks about her withdrawal from being a Scots activist on social media and talks about the reasons why she took these particular actions, contrasting the past when they publicly supported the use of Scots with now when they don't.

First of all, we can see evidence of ideologies about what it means to be a learner or a user or an advocate of a minoritised language?

In this case, for the speaker, it means being visible, public and online.

It also suggests language ideologies encountered by this person as prescriptivism. It's a set of constructed rules that aim to govern who can and can't use the language and in what forms and situations they can and can't use it in.

So, this this group who do the prescriptivism described here as gatekeeping. They are themselves Scots users, language activists, and they take this role of policing and potentially excluding others.

And this, the participant here contrasts that group to a new group that she now belongs to, which is inclusive and described as a safe environment where she can speak and use her Scots in a positive way. So, it's pretty clear here that choosing to learn and use a minority language like Scots involves more than just doing some book learning. But there are definite personal and emotional efforts that someone goes through, they wouldn't necessarily encounter if they were learning a majority language.

So finally to wrap up, I'd like to leave you with some thoughts about what we can do about these ideological aspects of Scots and what we can do to maybe challenge and question these beliefs that are maybe stopping us and other folk from using Scots as much as we could.

So first of all, we can recognise that language ideologies exist and that these are constructed beliefs and think about what they might be in reference to the Scots leid.

On a personal level, you can think about what you believe about Scots, where that comes from, whether it's based in reality or whether it's a belief that comes from society or a certain way of looking or growing up or education.

We can all learn more about Scots, not just the words and the sounds.

But learn a bit more the history of the language linguistically, how it works in Scotland and there's some resources there on the slide that you might be interested in looking at further.

And then if you can speak Scots already or if you're learning it, then use it. Use it as much as you possibly can in in situations where you think it might not be usual to use it because that will then help to encourage others to use Scots as well and help to build a big a safe and secure space for using Scots so that we're able to challenge these ideologies that tell us that it's maybe not appropriate.

Particular circumstances are there for particular reasons.

That's the end of the presentation. I'll finish now.

And here are my contact details for anyone who'd like to get in touch about my work or have any questions or comments. I hope you've found it interesting. Thank you very much.

Return to Unit 1.