3 Microaggressions

The European Commission has had specific regulations to address sexual violence and harassment since 2019. It recognises that this problem is directly related to gender bias. For this convention to be applied and respected, states and unions must collaborate. This can be seen in the following quote:

Violence and harassment at work is a widespread is a persistent phenomenon, with substantial adverse impacts for employees. This issue is entrenched in gender biases and stereotypes, and disproportionately affects women.

In September 2023, the Council adopted a position […] to ratify the Violence and Harassment Convention (ILO Convention 190)[35]. The 2019 Convention is the first international instrument setting out minimum standards on tackling work-related harassment and violence. Through effective cooperation with the International Labour Organization (ILO), the EU and its Member States played a crucial role in the adoption of the Convention.

Violence and harassment at work are based on discrimination that can have multiple causes, among which are gender stereotypes and prejudices. The graph below illustrates the main reasons people report discrimination according to data from Eurostat (2022).

Note: The image below is an interactive ‘hover to reveal’ graph. Additional bar chart information for each discrimination group appears when you hover over the different coloured sections of each bar.

It's important to emphasise in this regard that discrimination is not just an interpersonal issue, but rather that organisational culture itself fosters the emergence of multiple instances of discrimination and violence. For example, workplace bullying is closely related to organisational culture and is expressed through various practices, many of which are verbal.

Workplace bullying is closely bound up with organizational culture, the social position of the target, and her or his role within the community. It can comprise a vast array of behaviour or tactics that can be explicit and visible or subtler and hidden, including public ridicule and humiliation, unfair treatment and criticism, emotional attacks, verbal and physical abuse, professional discrediting and devaluation, intimidation, withholding of information, and excessive monitoring.

In fact, many studies show that this is not an isolated phenomenon. For example, 73% of UK civil servants claim to have been bullied or harassed at least once (Cabinet Office, 2018).

The seriousness of the phenomenon led the United Nations to consider that this problem should be understood and addressed within the framework of respect for human rights, as it affects the worker's rights to health, safety and dignity which are recognised through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The various international instruments designed in this regard serve as an umbrella for the development of specific national legislation that requires organisations to implement measures to protect this right.

In this context, the European Union recognises gender discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace as particularly important problems and dictates that organisations are obligated to establish mechanisms for effectively addressing bullying and protecting those affected by it.

Sexual harassment at work is considered as a form of discrimination on the grounds of sex by Directives 2004/113/EC, 2006/54/EC and 2010/41/EU. Sexual harassment at work has significant negative consequences both for the victims and the employers. Internal or external counselling services should be provided to both victims and employers, where sexual harassment at work is specifically criminalised under national law. Such services should include information on ways to adequately address instances of sexual harassment at work and on remedies available to remove the offender from the workplace.

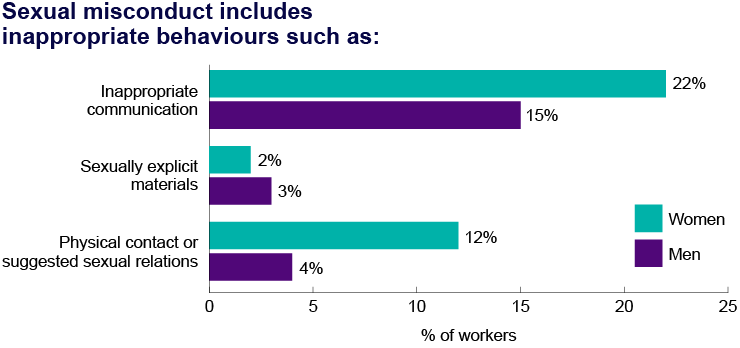

Sexually degrading attitudes and behaviours can be expressed in various ways at work and, as a Canadian study (Statistics Canada, 2021) illustrates, can affect one in four women and one in six men.

The severity of sexual harassment is also related to the fact that this problem tends to be persistent and widespread. As a statistic from the Australian Human Rights Commission (2018) shows, in more than half of cases the harassment lasts for more than six months, and 41% of those who experienced it were aware that other coworkers had experienced or were experiencing a similar situation.

This type of violence is taking on new nuances in work contexts mediated by new technologies. The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) asserts the seriousness of gendered hate speech in virtual environments, such as the use ICT to direct degrading and hateful language towards woman and girls and pointing out the victim’s gender (EIGE, 2022).

The general recommendation is to recognise cyberviolence against women and girls, adopt shared definitions to be able to identify and report it, and understand the continuum of violence between physical and virtual spaces.

This recognition, however, is even more difficult when the attacks occur in the form of microaggressions.

2 Communication styles