1.1 A brief history of inclusive growth

When you think of growth and economic development, Africa may not jump to the forefront of your mind. It is a continent often portrayed and associated with:

- underdeveloped infrastructures

- overdependence on natural resource revenues

- lacking market diversity

- chronic poverty

- being prone to political volatility and inefficient governance regimes

- high levels of aid dependency.

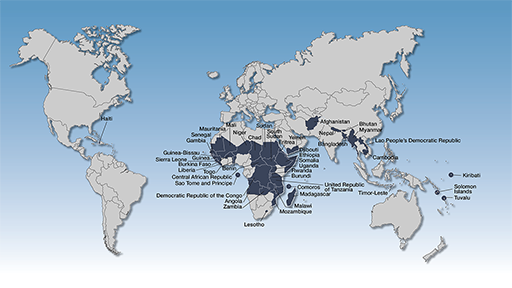

As of December 2020, 33 of the 46 countries classified as ‘least developed countries’ (LDCs) can be found in Africa. According to the UN, LDCs are deemed to have the lowest socioeconomic development in the world based on the Human Development Index [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] rating (UNDP, n.d.). This does not immediately conjure an image of an environment conducive for strong, stable and effective economic development.

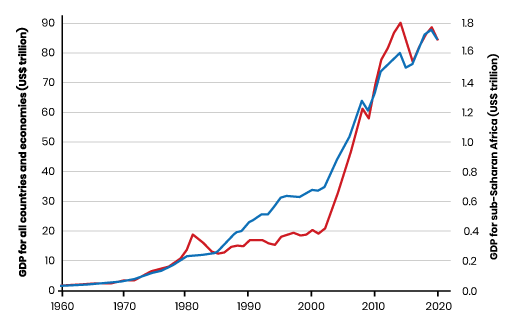

However, since the early 2000s, African growth patterns in terms of overall GDP have been rapid and consistent. Many countries experienced stable rates of growth that saw Africa as one of the fastest-growing regions in the world, second only to Asia (ODI, 2018). Africa is a continent that is rich in natural resources and many economies are tied to these commodities.

This dependency and lack of diversity in markets can leave countries susceptible to price shocks and global downturns or recessions, such as the oil price crashes of 2015 and 2018. Despite these vulnerabilities, overall, the trend in Africa has not only been growth but has been consistently higher than the global average. Even after a real GDP contraction of 2.1% in 2020, which is an evident impact of COVID-19 felt all over the world, the African Development Bank predicts that growth will return to 3.4% by the end of 2021 (AfDB, 2020).

While on the surface these figures may appear encouraging, the story behind them and patterns to this growth are far more complex. Across regions and countries there is significant variance and experiences to this growth, and this is a pattern that extends to levels of growth happening within countries. A key determining factor in driving inequalities is how the dividends of growth are distributed: although Africa’s economies in general are on an upward trajectory, not everyone is benefitting or getting a share. In fact, the divide between the richest and poorest in Africa is not reducing; it is widening. In 2020, the World Inequality Database reported that the top 10% of earners were capturing 50% of national income (WID, 2020). This story is not particular to Africa but is part of a broader global phenomenon. Currently, the world’s richest 1% have twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people (given a world population of 7.9 billion) (Oxfam, 2021).

The idea of inclusive growth (IG) has emerged over the past ten years as a way of framing this problem of deepening inequality. It is a response to the increasing recognition that, while absolute poverty levels have dropped significantly, the benefits remain concentrated in the hands of a few elites (Alexander, 2015). IG has become a driving tenet among development policymakers and multilateral agencies such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, United Nations and the African Development Bank. At its core is the argument that conventional conceptions of growth have failed to account for the inequalities gap because they equate growth solely in terms of economic outcomes. What is needed is a broader understanding of growth: something that incorporates social and political determinants, and is more participatory and inclusive of wider society.

Introduction