1.2 Chairing as leadership

Since COVID-19, the number of online work meetings has multiplied (Standaert, Muylle and Basu, 2022). For many, this has resulted in too many unnecessary work meetings, with little structure or understood purpose, leading to the often-used question, ‘could we do this in an email?’ (see Unit 5 of this course).

However, under effective leadership, work meetings can be an important resource for an organisation, facilitating strong discussions that elicit a range of opinions and produce high-quality decisions (see Mroz, Yoerger and Allen, 2018). The way a chair interacts with other participants sets the tone for what is considered appropriate communicative behaviour. The position of chair is one that requires considerable organisation and communication skill to manage the different interests present within the meeting while also holding the interests of the organisation and managing their own identity as leaders (Rogerson-Revell, 2011).

Chairing styles

Depending on the context of the meeting, there is a great degree of flexibility in the way chairs carry out their role. Factors such as meeting purpose, topic, formality and participant relations all influence the way chairing is carried out.

Much of the literature around chairing practice identifies two predominant styles of chairing leadership. These will be referred to as ‘participative’ and ‘directive’ chairing. Table 1 below summarises the main features of each style, along with their corresponding positive and negative effects.

Participative chairing

| Directive chairing

| |

|---|---|---|

| Features |

|

|

| Positive and negative effects |

|

|

Of course, it’s easy to stereotype chairing styles and think about them in binary terms. There are many different forms and functions of meetings, which may require different styles of chairing. The reality is that effective chairs draw on different styles depending on what is appropriate or required for the given meeting.

So far, you have considered different aspects of chairing styles and practices. In Activity 2, you will consolidate this learning by reviewing some of the examples of effective and ineffective chairing practices.

Activity 2 Reviewing chairing practices – how not to chair a meeting

Activity 2 Reviewing chairing practices – how not to chair a meeting

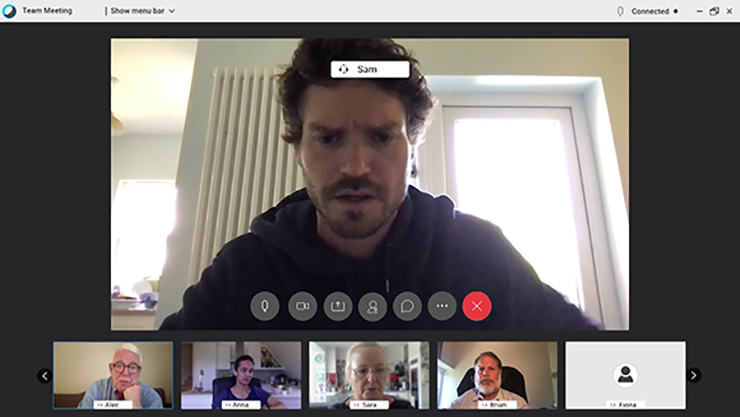

Watch Video 1 through once in full and then a second time while you make notes.

Transcript: Video 1 How not to chair a meeting

Make use of your learning on this course so far, and your own experiences of online meetings, and write down the examples of ineffective chairing you have noticed in the box below:

Discussion

Some of the ineffective practice examples are noted below – you may have noticed other examples too.

The chair:

- Is late. Being late is disrespectful to others and limits opportunities to fix any technical issues.

- Is unprepared.

- Dresses very casually and has stains on their hoodie.

- Is not clear to everyone due to poor lightning. This can disadvantage some participants e.g. those people who lipread.

- Doesn’t ask people to turn on their cameras at the start.

- Starts the meeting without an introduction and participants are given no time to ‘arrive’.

- Has not checked their microphone is working.

- Shows a lack of respect for Anna – is impolite to her and interrupts her.

- Did not send an agenda.

- Does not interrupt Alec when they keep talking for too long.

- Does not use professional language.

- Uses jokes or irony in the wrong situation.

- Does not prioritise raising an important topic 10 minutes before the end of the meeting.

- Asks Sarah for an opinion on the applications without giving her the chance to prepare.

- Interrupts Sarah several times disrespectfully during the discussion about the applications.

- Asks two people who remained silent for contributions after the end of the meeting.

- Does not check the chat box throughout the entire meeting.

- Shows little respect for others’ time – e.g. the meeting ends 10 minutes late.

Now that you have had a chance to consider different approaches to chairing and reflected on some of the problematic features, we’ll move on to some of the issues that can impact good and bad chairing.

1.1 Chairing practices