Research

Section 2, Activity 3

Research

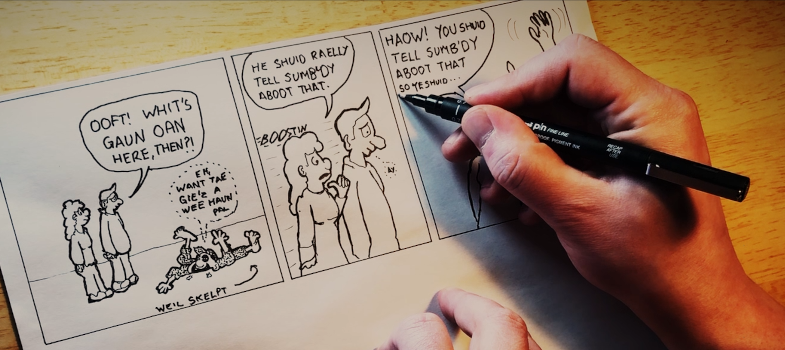

is a vital tool for any artist. Especially when, as a writer, you’re

putting words into other people’s mouths! In embarking on my poem

celebrating Elizabeth Melville, I hit a block as to which voice to

use, not to mention how daunted I was at the thought of writing a

poem for Melville at all, although I felt it would be a gap in the

collection if she wasn’t included, her contribution so significant,

being the first Scottish woman to have her work published in her own

lifetime (1603). She was a great poet, so it seemed folly to attempt

to write in her voice – she’d done it herself, brilliantly,

hundreds of years ago!

I got in touch with Dr Jamie Reid Baxter, the Elizabeth Melville expert, who gave me access to some letters that Melville had written to her son, one of them about her daughter’s death. Elizabeth Melville was a deeply religious Calvinist – her form of religion a terrifying, punitive one. She believed that this world was worthless, and that our only goal is to live a stainless life in order to pass through to heaven. In her letter to her son, she was clearly much more concerned that her daughter (his sister) had a crisis of faith on her deathbed than she was about the poor girl actually dying. This fact, astonishing to me as a parent, gave me the idea for the poem – to write it in the daughter’s voice, as she undergoes a crisis of faith on her deathbed, her appeal to her mother for help. This also struck me as a way to reach through time to the contemporary reader – any one of us can grasp that it would be completely understandable for a young person to struggle with her/his belief in a god who seems not to care about letting you die before your time.

The poem follows the same rhyme structure and iambic meter of Melville’s Ane Godlie Dreame, and the first stanza echoes lines from two ancient Scots language texts – the Border ballad, The Dowie Dens o Yarrow – ‘Oh, faither dear, I dreamed a dream, a dream o dule and sorrow’, and ‘When Alexander oor king wis deid…oor gowd was changit intae leid’.

Take a note in your Learning Log (opens in new tab) working through these aspects:

Before reading the poem, listen to my reading A Dochter's Dreame on Soundcloud. Take some notes on:

What the poem is about

Your impressions/feelings when listening to it

Any words you hear and are not sure

Then undertake some more research about the author on the Wee Windaes website: Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross

Now read the poem and:

think about the impact of the decision to use the daughter’s voice;

compare Melville’s poem with ‘A Dochter’s Dreame’ in terms of language use and message.

A Dochter’s Dreame

Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (c.1578–c.1640), Fife; poet; the earliest known Scottish woman writer to be published in her lifetime, her Calvinist dream-vision poem, Ane Godlie Dreame appeared in 1603; wrote to her son on his sister’s death that she – i.e, her daughter – was “hevylie trublit in mynd and body. Pryde wes the cheif thing that trublit hir, and the greving of hir deir mother, as she callit me then. Bot efter a soir battell, she gat a happie victorie, blissed be God. Nou she rests in the arms, all tears are wyppit away.”

Oh, mither dear, I dreamed a Dreame:

this fecht wi life hud left me deid

wi dule; I dreid that your esteem

I crave, is turnt frae gowd tae leid –

your howp in me is nocht.

It wis your ain Dreame, whilk ye wrocht

wi wurds like jewels, in a beuk,

the samin Dreame ye read tae me

in bairnhood; and, wi care, I teuk

your ilka wurd tae hert.

I fear the vaige I hae tae chairt

frae this hersh warld, whaur I hae failed,

through vainity, and pride (as ye,

aft-times, hae warned and richtly railed).

The voice was yours, I sweir,

in ma Dreame – sad and solitaire,

like a bird on a bare brainch, threap,

threapin me tae haud fast, white’er

suld pass – ice, fire, or warse: the dreep,

dreepin stang o misdout;

but I stumblit, could nocht cast oot

a laithly fear o aathing – shame

o masel, yer dochter wha suld

gie hersel to Him, whaes true name

is aa that can endure.

Torment, ma paiks; there is nae cure

fur lost sauls. Mither, tell tae me

aince mair yer Godlie Dreame, that I

may nocht be brunt in hell – oh, gie

ma saul the will tae pray!

The research process for Quines was fascinating, and, at times, challenging. The internet is a double-edged tool, indispensable yet unreliable. There were several instances where, with deeper digging, I discovered that the initial information I’d gleaned online was incorrect. On the other hand, at times, it was vitally useful.

Books played the biggest part in the process of research, both biographies and autobiographies – most of them second hand and out of print, which says a lot about the lack of status given to these extraordinary women. Some of them, for various reasons, haven’t made it into this collection. There are so many I could have chosen, as evidenced in the Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women (Edinburgh University Press, 1st edition, 2006, 2nd edition – The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, 2018), which was an invaluable resource.

Researching Quines has also stimulated me creatively in other directions. For example, the work of Arctic explorer, botanist, writer and film-maker, Isobel Wylie Hutchison has particularly captured my imagination. In her book North to Rime-Ringed Sun, about her Arctic journey in the early 1930s, she places a poem at the beginning of each chapter. These poems are, to my mind, perfect song lyrics, evoking the Arctic landscape with great eloquence and atmosphere, and I have set them to music, creating songs with a view to recording them for a CD. One of the bonuses of research is that it can often lead to further unforeseen avenues of creativity.