Reading 2 Penelope Davies, Death and the Emperor

Source: Davies, P. (2000) Death and the Emperor: Roman Imperial Funerary Monuments from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 158–62.

The Mausoleum of Hadrian

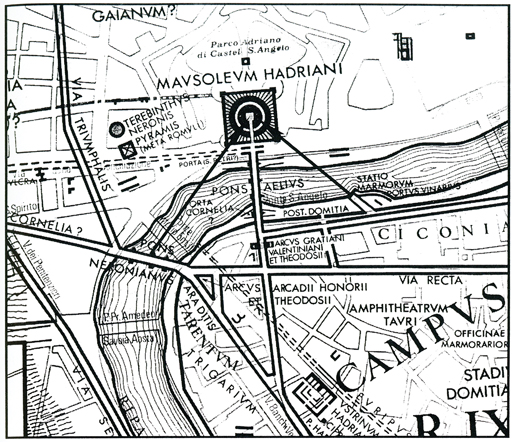

[p. 158] Hadrian’s Mausoleum stood on the west bank of the Tiber on the Ager Vaticanus (fig. 108).Footnote 91 Since the plain was marshland prone to flooding, it was not a salubrious place and was barely inhabited; even in the late first century, according to Tacitus, a pestilence decimated Vitellius’s troops when they set up camp there. Cicero tells us that it was farming ground in early times, and poor land at that; Martial and Juvenal add that it produced pottery and wine of rather inferior quality.Footnote 92 All the same, the plain was the location of luxurious horti from the first century b.c. on, and though hard to define, these private gardens appear to have covered most of the area. Among them was an estate belonging to Agrippina, daughter of Agrippa, and as her son Caligula reportedly received Jewish ambassadors in the property, there must have been a palace there.Footnote 93 Archaeological finds suggest that the buildings were magnificently decorated, and that the lifestyle they witnessed was extravagant. The Horti Agrippinae may have encompassed the Horti Domitiae, associated either with Nero’s aunt, Domitia Lepida, or with Domitian’s wife, Domitia Longina, daughter of Corbulo; it was in this estate that the Mausoleum was located.Footnote 94

Construction in the area may have fallen within these imperial gardens: a large building behind the later Mausoleum identified as a Naumachia;Footnote 95 and Nero’s infamous stadium, the Circus Gaii et Neronis, which appears initially to have been in private use but housed Nero’s public races and displays by 59, including his own games, the Neronia.Footnote 96 Public access to the circus must have been along the Via Recta, carried across the Tiber from the Campus Martius on the Pons Neronianus, built either by Nero or Caligula.Footnote 97 Scattered burials lined a network of other roads: the Via Triumphalis leading north from Nero’s circus [p. 159] and the Via Cornelia, which extended the Via Recta.Footnote 98 The construction of the Mausoleum spurred further burials in the area, as well as greater development: an embankment road between the tomb and the Tiber continued east up the riverbank and west to join the Via Cornelia near the circus.Footnote 99

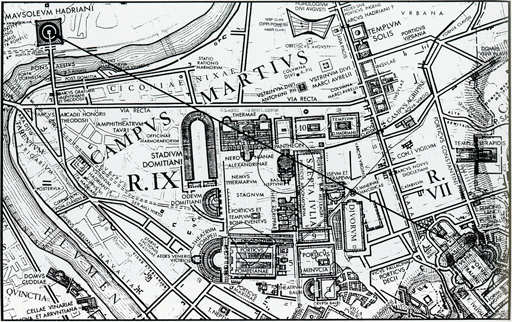

Romans often situated their tombs in their gardens.Footnote 100 In Hadrian’s case, scholars concur that the emperor intended his tomb to sit in a private extension of the Campus Martius, where he could build at will without needing the Senate’s posthumous decision for public burial. Indeed, the new Pons Aelius and Mausoleum changed the orientation of the plain to match that of the Campus Martius. Perhaps by situating his tomb across the river Hadrian hoped to evoke thoughts of the soul’s journey across the Styx or the Acheron to the Underworld in mythology, or the Egyptian custom of burying the dead across the Nile, an image that a nearby pyramidal tomb, the Meta Romuli, similar to but larger than the pyramid of Gaius Cestius (fig. 49 [not reproduced here]), must have conjured readily to mind, to say nothing of the Isiac cult center in the region.Footnote 101 As for the Mausoleum’s precise [p. 160] location within the estate, however, Boatwright comments, “So far no one has satisfactorily explained the unusual location of the Mausoleum, nor related Hadrian’s tomb and bridge to the rest of the Hadrianic city.”Footnote 102

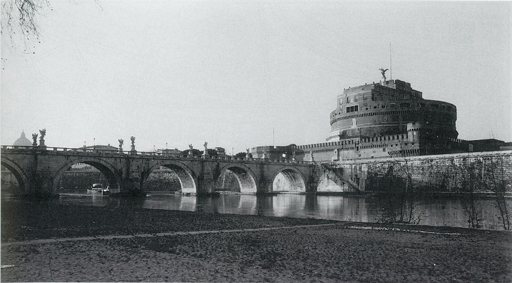

An analysis of the tomb’s relationship to its surroundings, and to buildings elsewhere in Rome, reveals that its site was not haphazardly chosen. The Mausoleum stood almost equidistant from two busy points for traffic on and across the river. One of these was the Pons Neronianus. As he crossed the familiar Neronian bridge, and especially when he stood at its midpoint on the river, a passerby had an unencumbered view of Hadrian’s entire funerary complex, bridge and tomb, which was much less easily obtained from either shore (figs. 108, 9). On the north side of the Pons Aelius a similar view presented itself (fig. 110): work on the Tiber embankments in 1890 uncovered a substantial tufa and travertine jetty, which scholars identify with the Ciconiae mentioned in literary sources.Footnote 103 A principal stopping point for Tiber traffic beyond the Forum Boarium dock area, this jetty was probably used for unloading cargo such as marble and wine from other parts of Italy and the empire, or as a waiting dock. It was certainly a focus of activity on the right bank and may have been the first port of entry to Rome for visitors from elsewhere. If so, it was from here that they received their first impressions of the empire’s capital.

Either of the scripted views presented a viewer with a sort of dynastic narrative. On the one hand, the very act of building a new mausoleum marked a break from Hadrian’s adoptive father, Trajan, and first-century predecessors; this separation was effected quite literally by the tomb’s location across the Tiber. Yet, while claiming a fresh dynastic start in this way, Hadrian was still fully conscious [p. 161] of the value of legitimizing devices and the legitimizing power of his institutional antecedents. In his choice of a circular dynastic monument, and in its proportions (both 300 feet at the base), he visually acknowledged Augustus, whose mausoleum stood, conspicuously, farther up the Tiber on the east bank.

From the Pons Neronianus or the Ciconiae, a viewer saw an inscription running along either side of the bridge similar to the inscription still visible on the Pons Fabricius, downstream from the Pons Aelius.Footnote 104 The Pons Aelius and the Temple of Divine Trajan and Plotina were the only two buildings that Hadrian signed with his name.Footnote 105 In the former case, his dynastic ambitions speak for themselves: Hadrian is heir to the now divine emperor, legitimate descendant of Trajan’s and Plotina’s “fictive family.” The bridge’s inscription had a similar purpose, as his choice of titles reveals:

imp. caesar divi traiani parthici filius divi nervae nepos traianus hadrianus augustus pontifex maximus tribunic. pot xviii cos. iii fecit

[The Emperor Caesar Trajanus Hadrianus Augustus, son of Divine Trajanus Parthicus, grandson of Divine Nerva, with tribunician power for the 18th time, in his third consulship made this]Footnote 106

Heir to Trajan the Divine, he also claims descent from the Divine Nerva, establishing his legitimacy through two generations of divi;Footnote 107 thus legitimized, he becomes the founder, like Augustus, of his own dynasty, embodied by his tomb, modeled after that of Augustus.

An even grander planimetrical scheme inscribed Hadrian’s descent from the deified Trajan into the cityscape. I argued in the previous chapter [not reproduced here] that by [p. 162] Hadrian’s time Rome had a spectacular new belvedere in the form of Trajan’s Column, from which a viewer could survey the city as a massive architectural stage. I also suggested that vistas from the column were carefully managed, and dramatically enhanced by the long, dark climb to reach the platform. Looking northwest from the top of the Column, a viewer would have recognized the Pantheon, a vast reflecting dome amid the gabled roofs of the city. Directly behind the Pantheon, she would have seen another circular building, Hadrian’s Mausoleum, and its crowning statue or tempietto rising above the Pantheon’s dome as if emerging from it – for a perfectly straight line unites the Column with temple and tomb (fig. 111). This planimetrical relationship must have implied a thematic link between the two circular buildings – just as sightlines had bound Agrippa’s Pantheon to Augustus’s Mausoleum a century and a half before – and that theme, I argued in Chapter 3 [not reproduced here], was the cosmos and Hadrian’s implicit role within them as cosmocrator.Footnote 108 A celestial building, the Pantheon celebrated all the gods, old and new. Hadrian moved within it during his lifetime as a quasi cosmocrator; in death he joined its gods, his image rising in the distance above its dome to express his newly divine status. If one were to look out from Hadrian’s Mausoleum, in turn – and the staircase inside suggests that one could – one would see the vast dome of the Pantheon in the mid-ground and, behind it, the Column of Trajan with its gleaming apotheosized statue of Trajan, an architectural metaphor, perhaps, for Hadrian’s descent from Trajan, the new god, and his association with the sun – Hadrian as a sunlike quasi reincarnation of Trajan.

[p. 163] In the form of his Mausoleum, then, Hadrian bracketed himself with Augustus. Yet, through careful siting of the tomb, he was also able to identify himself with Nerva and Trajan, and to imply his connection with the sun-god. The entire Mausoleum complex thus expressed his dynastic heritage while still establishing him as the founder of a separate line of rulers.

[…]

References

Boatwright, M.T. Hadrian and the City of Rome. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Boatwright, M.T. “The Imperial Women of the Early Second Century a.c.” AJP 112 (1991): 513–40.

Bodel, J. “Monumental Villas and Villa Monuments.” JRA 10 (1997): 5–35.

Buzzetti, C. “Nota sulla topografia dell’Ager Vaticanus.” QITA 5 (1968): 105–11.

Castagnoli, F. “Installazioni portuali a Roma.” In The Seaborne Commerce of Ancient Rome: Studies in Archaeology and History, ed. J.H. D’Arms and E.C. Kopff, 35–39. Rome: American Academy in Rome, 1980.

Flambard, J.-M. “Deux toponymes du Champs de Mars: ad Ciconias, ad Nixas.” CEFR 98 (1987): 191–210.

Gazzola, P. Ponti romani, Contributo ad un indice systematico con studio critico bibliografico. Florence: L.S. Olschki, 1963.

Grimal, P. Les jardins romains. Paris: E. De Boccard, 1943.

Guarducci, M. “Documenti del primo secolo nella necropoli Vaticana.” RendPontAcc 29 (1956–57) [1958]: 111–37.

Guarducci, M. The Tomb of St. Peter. New York: Hawthorne Books, 1960.

Humphrey, J. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986.

La Rocca, E. La riva a mezzaluna: Culti, agoni, monumenti funerari presso il Tevere nel Campo Marzio occidentale. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1984.

Le Gall, J. Le Tibre, fleuve de Rome dans l’antiquité. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1953.

MacDonald, W.L. The Pantheon, Design, Meaning and Progeny. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Marchetti, D. “Scoperte nella Regione IX.” NSc (1980), 153.

Palmer, R.E.A. “Studies in the Northern Campus Martius.” TAPS 80.2 (1990): 52–55.

Pierce, J.R. “The Mausoleum of Hadrian and the Pons Aelius.” JRS 15 (1925): 75–103.

Richardson, L., Jr. A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Robinson, O.F. Ancient Rome: City Planning and Administration. London-New York: Routledge, 1992.

Tomei, M.A. “La regione Vaticana nell’antichità,” In Adriano e il suo Mausoleo, ed. M. Mercalli, 23–38. Milan: Electa, 1998.

Tomei, M.A. “Nuovi elementi di recenti acquisiti.” In Adriano e il suo Mausoleo, ed. M. Mercalli, 55–61. Milan: Electa, 1998.

Tomei, M.A. “Il Mausoleo di Adriano: La decorazione scultorea.” In Adriano e il suo Mausoleo, ed. M. Mercolli, 101–47. Milan: Electra, 1998.

Waurick, G. “Untersuchungen zur Lage der römischen Kaisergräber in der Zeit von Augustus bis Constantin.” JRGZM 20 (1973): 107–46.

Footnotes

- 91 See Waurick (1973), 118–20; Boatwright (1987), 161–65; M. A. Tomei, “La regione Vaticana nell’antichità,” in Adriano e il suo Mausoleo, ed. M. Mercalli (Milan, 1998), 23–38; P. Grimal, Les jardins romains (Paris, 1943), 141–42.Back to main text

- 92 Tac. Hist. 2.93; Mart. Spect. 6.92.3; Epigr. 1.18.2, 6.92.3, 10.45.5, 12.48.14; Juv. 6.344; Cic. Leg. Agr. 2.96. See Richardson (1992), 405; Boatwright (1987), 165–67; Tomei (1998).Back to main text

- 93 Philo. De Legat. ad Gaium 2.572; Tomei (1998), 28.Back to main text

- 94 S.H.A., M. Ant. 5.1. Tomei (1998), 33.Back to main text

- 95 J. Humphrey, Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing (Berkeley-Los Angeles, 1986), 550, 683 n. 42. As the Gaianum: C. Buzzetti, “Nota sulla topografia del-l’Ager Vaticanus,” QuadIstTopAnt 5 (1968): 105–11; Boatwright (1987), 167; Tomei (1998), 32–33.Back to main text

- 96 Humphrey (1986), 545–52; Tac. Ann. 14.14, 15.44; Suet, Ner. 22.2; Pliny, HN 37.19. F. Magi, “Il circo Vaticano in base alle più recenti scoperte, il suo obelisco e i suoi ‘carceres,’” RendPonAcc 45 (1972/73): 37–73; Boatwright (1987), 165–66; Richardson (1992), 83–84.Back to main text

- 97 See Robinson (1992), 85; Tomei (1998), 27; J. Le Gall, Le Tibre, fleuve de Rome dans l’antiquité (Paris, 1953), 74–93, 205–11. Contra: Boatwright (1987), 166; Grimal (1943), 140.Back to main text

- 98 Boatwright (1987), 167; M. Guarducci, “Documenti del primo secolo nella necropolis Vaticana,” RendPontAcc 29 (1956–57) [1958]: 111–37 (1960); idem, The Tomb of St. Peter (New York, 1960); Buzzetti (1968), 105–11; Waurick (1973), 119–20.Back to main text

- 99 Boatwright (1987), 167; J. R. Pierce, “The Mausoleum of Hadrian and the Pons Aelius,” JRS 15 (1925): 75–103, esp. 96–98.Back to main text

- 100 Waurick (1973), 120; Bodel (1970).Back to main text

- 101 On the Meta Romuli and Isiac cult, see Tomei (1998), 25 and 35.Back to main text

- 102 Boatwright (1987), 162.Back to main text

- 103 See E. La Rocca, La riva a mezzaluna: Culti, agoni, monumenti funerari presso il Tevere nel Campo Marzio occidentale (Rome, 1984), 60–65; D. Marchetti, “Scoperte nella Regione IX,” NSc (1890): 153; idem, “Di un antico molo per lo sbarco dei marmi riconosciuto sulla riva sinistra del Tevere,” BullCom (1891): 45ff.; idem, “Scoperte nella Regione IX,” NSc (1892): 110ff.; F. Castagnoli, “Installazioni portuali a Roma,” The Seaborne Commerce of Ancient Rome: Studies in Archaeology and History (Rome, 1980), 35–39; J.-M. Flambard, “Deux toponymes du Champs de Mars; ad Ciconia, ad Nixas,” CEFR 98 (1987): 191–210: R.E.A. Palmer, “Studies in the Northern Campus Martius,” TAPS 80.2.2 (1990): 52–55; Richardson (1992), 81–82; LTUR, 1.267–69. s.v. Ciconiae (C. Lega).Back to main text

- 104 P. Gazzola, Ponti romani: Contributo ad un indice systematico con studio critico bibliografico (Florence, 1963), 41–42, no. 40.Back to main text

- 105 Contra: S.H.A., Hadr. 19, which mentions only the temple.Back to main text

- 106 CIL 6.973.Back to main text

- 107 On the power of this heritage, see W. Weber in CAH XI.300.Back to main text

- 108 See also MacDonald (1976), 100, on the Pantheon and tomb and cosmos.Back to main text