5 Textual meaning – organising messages to make sense in context

In this section we will look at how we organise our messages. This is an aspect of the textual metafunction. The lexicogrammatical choices we make not only construct a representation of experience (the ideational metafunction) and signal social roles and status (the interpersonal metafunction), but also provide a way of organising a message so as to make it accessible to the listener/reader, taking into account the context, channel and medium in which the text is produced. The first activity in this section is intended to show how language is packaged in order to help the reader make sense of what is being talked about. Three key questions can be asked about any act of communication which help to determine how it is or needs to be organised:

- Is it planned or spontaneous?

- Is it interactive or more of a monologue?

- Does the verbal message stand alone or does it work with other modes of meaning – e.g. images, pointing and gesture?

These three variables form a spectrum of possibilities which in SFL is called a mode continuum. At one end of this spectrum, face-to-face conversation would normally be spontaneous and interactive, and the verbal language used would normally be accompanied by physical gestures. In many cases, language might be taking second place, for example when it is mainly being used to accompany actions. At the other end, an academic article will be carefully planned, with no reader input, and with very few other modes of meaning (though in some cases, graphs, diagrams and charts may well be used alongside the words). This cartoon above plays on an apparent mismatch between the highly planned, wordy monologic mode of expression being used by the person in the pond and the apparent need for spontaneous, action-focused talk, given the situation.

However, there is no clear cut distinction between speech and writing. The mode continuum is the movement from more spontaneous spoken-like language to more formal, written-like language. Face-to-face informal conversation between friends may have characteristics similar to written communication between friends while a political speech may be organised in ways similar to newspaper reports. Communications via phones and the internet are useful in demonstrating the ways in which contextual variables, such as how well the interactants know each other, where they are, and the immediacy of response, can all work to blur the distinction between grammar in speech and in writing. For example, when exchanging text messages or chatting on social media, our language often reflects the relatively immediate timeframe and extent of contextual knowledge shared between participants, aspects which are often associated with conversation.

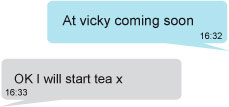

Take this brief exchange of texts:

The second texter has responded knowing that in fact ‘vicky’ is the name of a nearby park (Victoria Park) and both participants are working on the basis that the communication will be almost instant, because the second person will be making a meal to suit the timing of the first person’s journey home ‘soon’. The way in which texts are nowadays represented on a screen, using speech bubbles, is an acknowledgement of their conversational nature, as is the tendency to omit any form of punctuation. Because of the way in which text messages automatically flag the sender’s name, there is no need for greeting or signing off, which is more like face-to-face conversation (where we know who is speaking because they are in front of us) than typical written contexts. On the other hand, there are features here that are associated with writing rather than speech – e.g. the first text message omits the personal pronoun ‘I’ and the verb ‘am’, which might be expected in speech abbreviated to I’m (though the pronoun is retained in the reply), and the second uses x to indicate affection (or a kiss).