A Bowie quote that will likely feature in any obituary is this statement from 1997: ‘I don't know where I'm going from here, but I promise it won't be boring.’ It is as applicable to his art as it was to his life. It’s perhaps not surprising that today is a day full of clichés about his chameleon nature, his endless reinvention of himself and his lack of any fixed identity, but these seem to miss an essential point about the man and his creative output. The artifice was both form and content of the art.

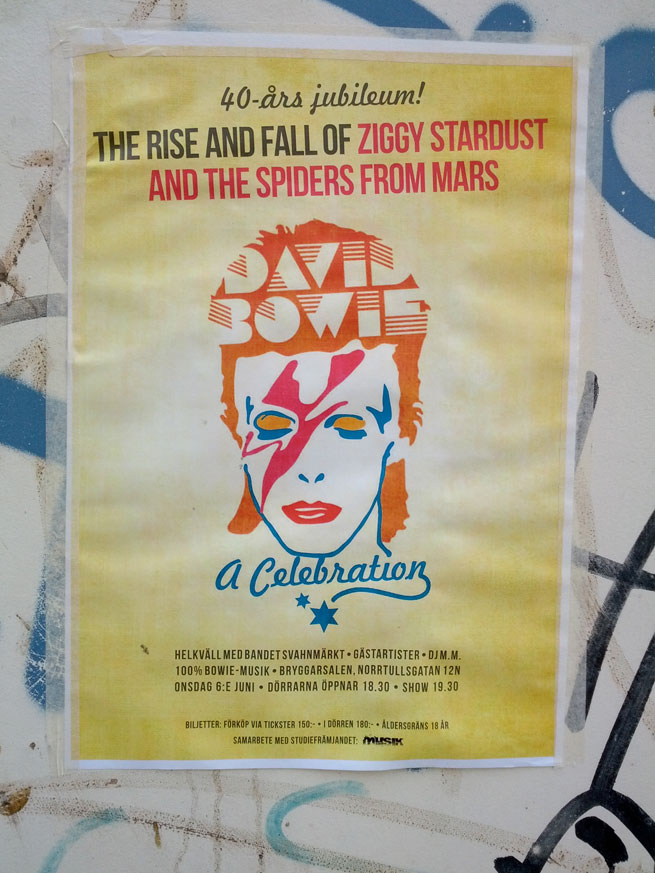

A poster advertising a celebration of Bowie's work

A poster advertising a celebration of Bowie's work

He seems to have seen identity as something constantly on the horizon of our perception, always becoming, never merely being – an arrival that always included its departure: ‘When the kids had killed the man / I had to break up the band’ as he sang of his most famous creation, Ziggy Stardust in 1972. This might explain why the extra-terrestrial (whether human or alien) was an abiding metaphor he returned to from the early days of Major Tom in the song Space Oddity (1969) through his re-appearance in Pierrot costume on Ashes to Ashes (1980) and most recent embodiment in the video to his latest single Blackstar in which a woman approaches a figure in a spacesuit lying on the ground, she opens the visor to reveal a jewel-encrusted skull which is then carried off in a glass box as an object of worship – perhaps he was telling us that this was to be the final transformation.

And in a wry reference back to Major Tom’s ‘Here am I, floating in a tin can, far above the world’ he portrays himself in ‘Lazarus’, eyes bound like a latter day Tiresias, floating inches above a hospital bed, singing ‘Look up here man, I’m in danger/ I’ve got nothing left to lose./I’m so high it makes my brain whirl.’

The prettiest star fallen to earth.

The title of that final song (and album) Blackstar also throw light on his conception of creativity and identity. As Wikipedia tells us: ‘A black star need not have an event horizon, and may or may not be a transitional phase between a collapsing star and a singularity.’

Throughout his career, Bowie played with this tensions between what is, what might be and the point of no return as reflected in early songs such as 1971’s Changes: ‘I turned myself to face me, but I haven’t caught a glimpse’; his exploration of Fame (1975): ‘Puts you there where things are hollow’; to his almost Beckettian: ‘From nowhere to nothing / and neither way back’ from If You Can See Me on his penultimate album The Next Day (2013). Being and nothingness his polar conductors.

But best leave the last word to Bowie – it can’t be an accident he included them in the last track of his final album, released on his 69th birthday and just three days before his death, the highly ambiguously titled, I can’t give everything away:

Seeing more and feeling less

Saying no but meaning yes

This is all I ever meant

That’s the message that I sent.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

‘Saying no but meaning yes’, could mean even though he had to say no he couldn’t help deep down he really wanted to say yes.