It is now over 25 years since Jim Womack and his colleagues first published their study of global automotive production systems, entitled “The Machine that Changed the World”[i]. The book presented the findings of a thorough comparative study of the productivity of automotive manufacturers. The authors demonstrated the ways in which manufacturers such as Toyota had moved the paradigm of how cars should be made from the Ford-based mass production system to one of lean production. The impact of this study has been profound, leading to large scale changes in our understanding of how products and services can be produced more efficiently whilst better meeting customers’ needs.

In the following 25 years manufacturing practices have continued to improve across the world and the ideas around lean thinking have further developed. The globalisation of markets has also encouraged further development and innovation in the auto market. The practices seen at the Toyota assembly plant at Burnaston only hint at the sophistication of knowledge, planning and organisation underpinning how cars are made today.

Customer choice without process complexity

Ford production line 1913

The original Ford mass production system is well-known for its lack of product variety and customer choice. Even early applications of lean thinking tended to focus on cost reduction and the elimination of waste more than process flexibility. However, market changes have forced modern car producers to simultaneously achieve two potentially conflicting aims. First they have to provide the customer with a highly customised variety of the product they want, with many permutations and combinations of options. Second they have to achieve this without excess design and manufacturing costs. Lower costs are achieved by careful platform designs where components are shared across many ranges of cars, leading to economies of scale in the component manufacture and distribution. Historically each manufacturer would produce platforms for each continental market.

Ford production line 1913

The original Ford mass production system is well-known for its lack of product variety and customer choice. Even early applications of lean thinking tended to focus on cost reduction and the elimination of waste more than process flexibility. However, market changes have forced modern car producers to simultaneously achieve two potentially conflicting aims. First they have to provide the customer with a highly customised variety of the product they want, with many permutations and combinations of options. Second they have to achieve this without excess design and manufacturing costs. Lower costs are achieved by careful platform designs where components are shared across many ranges of cars, leading to economies of scale in the component manufacture and distribution. Historically each manufacturer would produce platforms for each continental market.

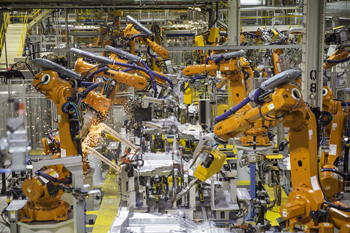

Today platform design is common across all continents, leading to truly global products. Often these products are designed by dispersed design teams spread all over the world, including people from established suppliers. VW Group, for example, produce over 200 varieties of car with a strategy for just four platforms. The variety and choice is added through modular design and assembly where variants can be produced side-by-side without disrupting the manufacture and assembly process. This requires some really clever design and production engineering. Factories like the Mini facility achieve mass customisation on a daily basis. Various car varieties combined with hundreds of available interior and exterior trim options results in quadrillions of individual car possibilities with each customer specified variant following the other on the production line.

Kaizen as a key ingredient

The assembly of vehicles requires some very careful planning and considerable investment, including a skilled workforce able to deliver different error-free vehicles in real time. The job of assembling a complete car takes many hours. The Burnaston factory needs to complete production of one car every 84 seconds to keep pace with demand and hence the assembly task has to be broken down into multiple steps that each take no longer than 84 seconds. If a task takes longer, the stage in the process has to be duplicated adding to costs. Any variation in how long a step takes would seriously disrupt the flow of work, so every single action at every step in the process is controlled and continuously improved. This intensity of improvement activity is a clear characteristic of Toyota’s operations which has been emulated by many other companies worldwide.

Supply Chain coordination

Landrover Discovery production line

Landrover Discovery production line

Historically, one focus of attention in lean systems was the just-in-time supply that is still evident as an industrial practice. Many components arrive just minutes before they are used on the assembly lines, placing burdens on suppliers and logistics to deliver the right mix of product absolutely on time. Originally this practice was partly borne out of need in the space-constrained Japanese factories but there are other behavioural benefits of not having spare stock to waste. This just-in-time concept has grown into a much more sophisticated view of supply chain coordination. The whole supply chain has to follow the volume and short-run mix variation if excess work-in-progress, pipeline stocks and waste are to be avoided. The problem is further compounded by supply chain dynamics that create instability if demand uncertainty and variation are not managed with a supply chain perspective.

Given that typically 70%+ of manufacturing cost is held within the supply chain, auto manufacturers are only as competitive as their supply chains allow. Supply chains are much more carefully managed and coordinated than we ever envisaged. In the auto sector many suppliers have to be shared across competitors, so advantage is created by the ways in which supply relations are managed.

The emergence of growing auto markets in China, India and Russia have forced auto manufacturers to rethink where their market centre of gravity resides. To tap into the higher volume segments of the 12 million units-per-year market in China it is not sufficient to move your own assembly facility there: you have to take your entire supply chain with you and also deal with local infrastructure issues before you are fully established. All of this requires considerable investment and exposure to risk.

Transfer of ideas

The use of lean thinking ideas transferred very rapidly to other high volume manufacturing organisations away from the automotive sector. Even more complex manufacturing environments, such as aerospace, have been able to learn from the automotive experience. Perhaps the most interesting development have been in service sectors such as healthcare where Toyota’s principles are being more widely adopted. In the US Thedacare use the lean tool of Jidoka to allow failing processes to be stopped before they do harm. Virginia Mason hospitals have their own production system based closely on that from Toyota. Elsewhere local councils, police services and even universities have tried to apply the very same principles. If we look hard enough we can see the use of lean practices in parts of everyday life. We can be sure that the automotive sector is not only continuing to adapt and improve itself, but through the adaptation and spread of its techniques to manage operations more effectively in other sectors it is continuing to change the world.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews