One of the shocks of the Brexit referendum was that, while Scotland voted emphatically to stay in the European Union, Wales voted out. This demolished the received wisdom aligning Euro-scepticism with the political Right since Wales as a whole has tended to lean Left since the early twentieth century. The result also surprised commentators because Wales has been the beneficiary of so much EU funding. To some, it looked like the turkeys had voted for Christmas.

That, of course, is a gross over-simplification of an outcome which resulted from a complex set of inter-related factors. Various suggestions have been put forward to explain the Leave vote as a whole, including wealth inequality, an educational divide, young vs old, the influence of the right-wing print media, and a trans-national revolt against established elites. These would all have had a significant impact on the result in both Wales and Scotland. However, they don’t tell us why these two nations, which claim a dubious Celtic kinship and which occupy similarly devolved positions within the United Kingdom, voted differently.

However, that question can be addressed by examining how the Welsh and the Scots understand the histories of their respective nations. This is a potentially revealing angle because ideas about the past provide the foundation for national identities in the present. The glories and triumphs of yesteryear, the collective endurance of vicissitudes long past, the belief in shared origins and collective experiences: these are the things which provide the raw materials from which notions of ‘we, the people’ are built. That point is significant for this article because during the referendum campaign Brexiteers tended to couch the referendum as a choice between two Unions, the British and the European. In this context, how the Welsh and Scots voters view the British state and the historical landscape it occupies, become important.

Professor Roger Scully of the think tank, Wales Governance Centre, discusses the potential implications and opportunities for Wales post-Brexit with Dr Jo Hunt and Dr Rachel Minto of Cardiff University. Created as part of Brexit Hub on OpenLearn.

Superficially at least, there are a lot of similarities between popular portrayals of the national past in Wales and Scotland. In both countries, the rise of nationalism has been fuelled by the decline or removal of forces which traditionally helped to hold the United Kingdom together; i.e. Empire, Protestantism and threats from mainland Europe. In both cases the result has been the growth of a historical narrative in which struggle against unjust English dominance has become the prevailing theme. Stories of resistance against English power, particularly during the Middle Ages, have thus garnered considerable cultural traction. Hence in 1997, the prospect of regaining self-government after centuries of rule from Westminster helped to secure Yes votes in both the Welsh and Scottish devolution referendums.

Tellingly, however, while almost three-quarters of participating Scots voted in favour of a Scottish parliament and 65 per cent supported giving it tax-varying powers, barely 50 per cent of Welsh voters supported the watered-down devolution offered to Wales in 1997. Moreover, in 2016, the SNP secured almost 50 per cent of the available seats in the Scottish parliament, while in the same year Plaid Cymru won only 20 per cent of those in the Welsh Assembly. Already we begin to see a broad correlation between different levels of enthusiasm for political nationalism on the one hand, and the different outcomes of the Brexit vote on the other.

Nicola Sturgeon, the current First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party

Nicola Sturgeon, the current First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party

In Scotland the SNP have in recent years positioned their brand of nationalism as avowedly civic, eschewing the ethnocentricism of the party’s formative years. Now they argue that to be Scottish you merely need to live in Scotland and buy into the principles of fairness and progressivism with which the mainstream nationalist movement has associated itself. In this vision of Scottishness, membership comes through territory and values rather than blood and shared history. Nonetheless, ideas about the past play an important role in underpinning even this liberal form of national sentiment. If we strip away the touristic trappings of tartanry and bagpipes, Scots tend to think of themselves not as Celts but as a mongrel people. Their shared identity was purportedly forged on the anvil of medieval English imperialism, which hammered the Scottish people into existence out of a motley collection of Picts, Gaels, Vikings, Saxons and of course the Scots themselves (hailing confusingly from Ireland). Scottish identity thus has no clear ethnic core, nor does it have any strong linguistic element. Gaelic is the preserve of a small minority of the population, while for many the Scots language is seen as a dialect rather than a national tongue. All of this makes a version of nationalism based on participation rather than ancestry that much easier to sustain, just because there are relatively few criteria available which might serve to exclude.

Moreover, despite its protestations of modernity, political nationalism in Scotland relies quite heavily on a cultural inheritance from the past. The Holyrood government has already been accused by some teachers, historians and media commentators [1] of using the school history curriculum to deliver a radical nationalist agenda, while research by sociologists Richard Kiely, Frank Bechhofer and David McCrone [2] has shown that for most Scots birth and blood trump territory as markers of belonging. Crucially, popular understandings of the national past are also replete with European connections. These include the Auld Alliance with France, the influence of Roman law on Scottish jurisprudence, the traditionally continental character of Scottish education, and Scotland’s contribution to the European Enlightenment. In this way, the nation is positioned within the history of European rather than British civilisation. Indeed, the ongoing popularity of William Wallace as a totem of national liberty, immortalised in the 1992 blockbuster Braveheart, is just one example of how resistant retellings of the Scottish past have become to notions of a shared British history.

EU flags

EU flags

So here we have a version of national identity that characterises Scotland as a European nation and offers few excuses to prohibit membership on the grounds of ethnicity or language. Of course it is difficult to establish a concrete correlation between that and the fact that 62 per cent of Scots recently voted to remain in the EU. Nonetheless, it does seem reasonable to posit a connection, especially given the different outcome in Wales.

Mainstream Welsh nationalism, articulated primarily by Plaid Cymru, now also positions itself as civic rather than ethnic. Unlike the Scots, the Welsh can lay claim to an ethnic identity which, while mythic, is racially coherent. This is based on their supposed descent from the Celts who occupied Britain before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons during the early Middle Ages. In Wales, therefore, the materials for constructing an identity based on blood and ancestry are more abundant than in Scotland. Nor is there any comparable tradition in Wales of cultural exchange with the continent, or of placing Welsh history within a European context. That is not to say that such interactions did not take place or that scholars have failed to examine Wales within a broader European setting. The point is instead that popular imaginings of the Welsh past nowadays still tend to be dominated by the relationship with, and struggle against, England.

There is undoubtedly a lot of cultural potential in Welsh complaints of ill-treatment by the English. Wales’s last independent prince was conquered and killed in 1282. Then in the early sixteenth century the principality, already under English control, was formally annexed. The cultural nationalists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw both conquest and union in broadly favourable terms. Over the last hundred years, these events have become associated with foreign oppression and the suppression of national freedom. This stands in marked contrast to the story which the Scots can tell, of repeatedly fighting off the English during the Middle Ages before entering willingly into a union of equals in 1707. However, that sense of historical injustice has not led to a Welsh separatist movement on the scale of that found in Scotland. Owain Glyndŵr is undoubtedly a national icon but not on the scale of Wallace. Pilgrims don’t flock to the location of his 1404 Welsh parliament in Machynlleth in the way they do to the site of Wallace’s 1297 victory over the English at Stirling Bridge.

The iconic statue of Owain Glyndŵr in Corwen, Wales

The iconic statue of Owain Glyndŵr in Corwen, Wales

Despite the polemical potential of Welsh history, there seems to be little appetite in present-day Wales for independence. The state of the Welsh language may be in part responsible for that. On one level its resilience acts as an ever-present reminder of the historical distinctiveness and Celtic origins of the Welsh people. Crucially, however, it is not successful enough to offer a unifying principle of Welshness. The former industrial heartlands of south-east and north-east Wales remain predominantly English speaking. This is partly a legacy of the hundreds of thousands of English immigrants who settled in those areas between 1851 and 1911 [3]. Moreover, those same regions were in the early twentieth century at the forefront of the labour movement in Wales, whose rhetoric tended to paint national boundaries as a bourgeois irrelevance in the struggle for working-class identity. In that context, Welsh was a hindrance rather than a help to calls for the workers of the world to unite. So while the language now occupies an official status equal to that of English and is a compulsory subject in schools, today only 19 per cent of those living in Wales speak it, according to the 2011 census. That is certainly far more than speak Gaelic in Scotland, but it is still only a minority of the population. The result is that Welsh does indeed impact upon notions of identity to a far greater extent than Gaelic but often divides rather than unites those who speak it and those who do not.

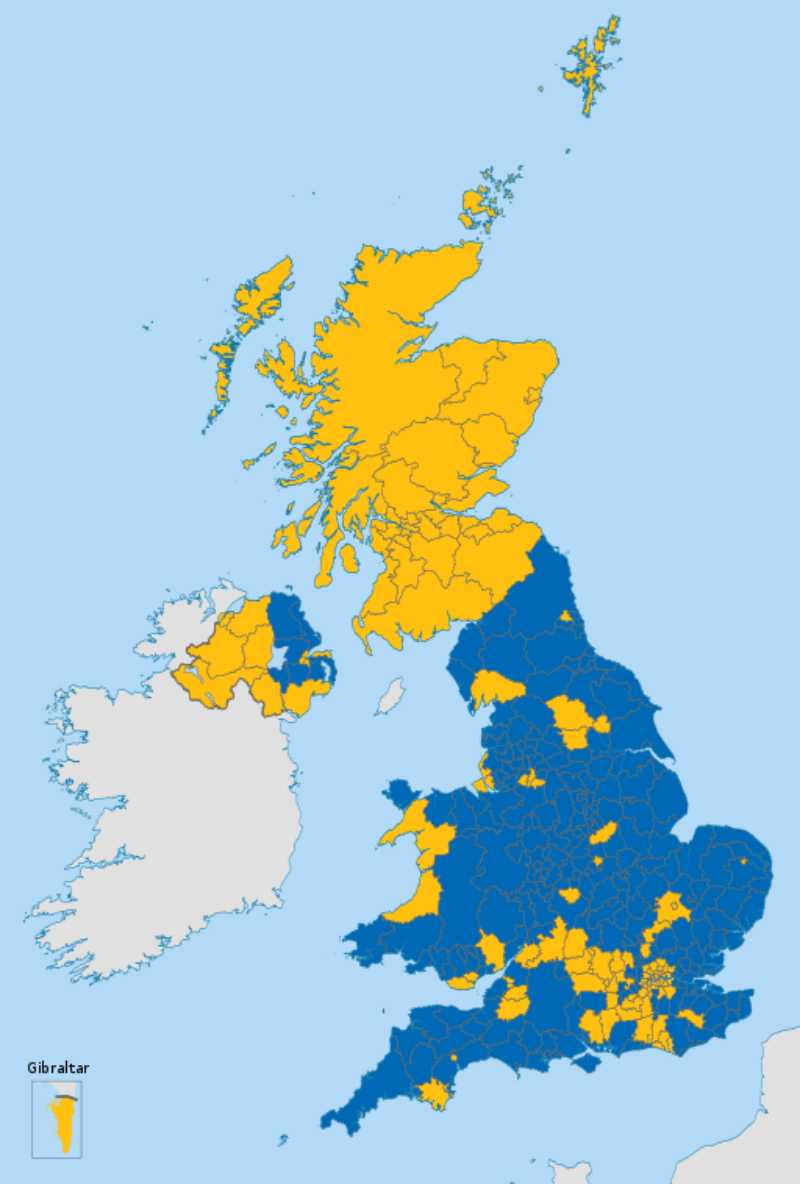

Map showing voting results from the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016 (Yellow: Remain - Blue: Leave)

Map showing voting results from the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016 (Yellow: Remain - Blue: Leave)

So what does all this tell us about the Brexit vote? Well, if we remove the young and cosmopolitan population of Cardiff from the mix then we find that the two counties with the most Welsh speakers, Gwynedd and Ceredigion, also saw the highest percentage of votes to remain in the EU. These areas were again near the top of the table for Yes votes in the devolution referendum of 1997 [4] and have voted for Plaid Cymru AMs in every Assembly election since [5]. This point is relevant because of one of the key arguments of the Leave campaign related to British sovereignty. The devolution referenda and electoral results we have already looked at suggesting that unionism is a more potent force in Wales than in Scotland. Yet, those from Welsh-speaking areas seem less attached to the British state and, in the terms set out by Brexiteers, therefore more willing to vote against it.

By couching the Brexit vote as a choice between the United Kingdom and a European super-state, Leave campaigners sought to mobilise British national sentiment. Their victory suggests that this was a successful strategy, but an unintended consequence was that Welshness and Scottishness were also brought into play. For Scots the inevitability of union with England has in recent decades been called into question – the small margin in the 2015 independence referendum is clear evidence of that. This, in turn, has enabled a flourishing vision of Scotland as a historically European nation with a welcoming and inclusive national character. The accuracy of that rosy depiction is irrelevant. What matters is its grip on the national psyche and, by extension, its role in clearing the way for more Scots to vote Remain than Leave.

In Wales, the choice between these unions, British and European, interacted with identity politics somewhat differently. Here the historical materials which shore up the national self-image have produced a version of nationalism which, despite the efforts of Plaid Cymru, remains more ethnically insular, less overtly European, and is fractured rather than united by language. This may be one reason why, when forced by political rhetoric into a choice between the British state and the European community, 52.5 per cent of Welsh voters chose the former. One factor of many certainly, but a factor nonetheless.

A better understanding of Brexit

‘The Weakness of European Wales’ was first published in the magazine PLANET: The Welsh Internationalist, volume 225.

Planet can be contacted on Twitter as @Planet_TWI , or on Facebook at Planetmagazine.CylchgrawnPlanet

A version of this article with additional links to further reading can be found at The Open University’s ‘Open Research Online’ repository, see here.

References

All EU referendum results cited in this article were taken from the Electoral Commission website: http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/find-information-by-subject/elections-and-referendums/past-elections-and-referendums/eu-referendum/electorate-and-count-information

[1] Graham Grant, ‘New Scottish school curriculum teaches students Britain is an “arch-imperialist villain”’, Daily Mail (19 May 2012) http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2146719/Anger-SNP-rewrite-history-New-school-curriculum-downplays-role-British-Empire.html

[2] Richard Kiely, Frank Bechhofer and David McCrone, ‘Birth, blood and belonging: identity claims in post-devolution Scotland’, The Sociological Review vol. 53, issue 1 (February 2005)

[3] Coalfield web materials from the University of Wales South Wales’ Coalfield Collection: http://www.agor.org.uk/cwm/about.asp

[4] Welsh Referendum Live - The Final Result, BBC News, (1997): www.bbc.co.uk/news/special/politics97/devolution/wales/live/index.shtml

[5] Election results, National Assembly for Wales, accessed 2018: http://senedd.assembly.wales/mgManageElectionResults.aspx?bcr=1

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

Wales has a strong connection to a pre-Roman past (labelled as 'Celtic' by historians). This is in no doubt. So I am wondering why this is even being questioned.