3.3 A body–world interconnection

Our consciousness of our bodies remains fundamentally tied up with our everyday embodied activities and relationships. The body thus represents both our particular view of the world as well as our Being-in-the-world (Heidegger, 1962 [1927]). Martin Heidegger (2001) draws a distinction between corporeal things and the body, questioning whether the sense of embodied selfhood that we all possess needs to coincide with the limits of a corporeal body. The corporeal thing stops and is bounded by the skin whereas our sense of embodied selfhood – our bodiliness – may extend beyond this ‘bodily limit’. Heidegger uses the example of pointing, where our sense of bodiliness does not stop at the fingertip but, instead, stretches out beyond the skin to the object captured in our gaze. Perception, action and interaction are interconnected as body and world merge, at least to a degree. Our bodies, phenomenologists argue, are not just contained by what is inside our skin; they reach out into the world.

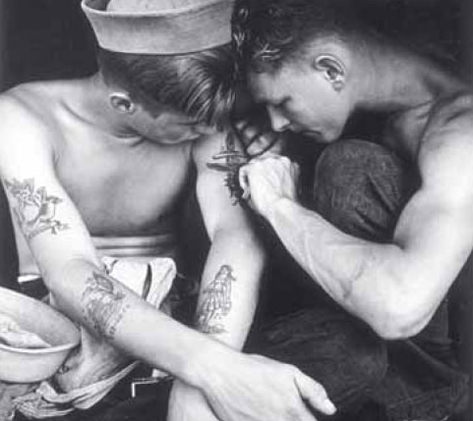

Take, for instance, the experience of a footballer who has just kicked a long ball towards the net. As the ball swerves too far in one direction, the footballer leans in the other direction attempting to pull the ball back. The footballer's body and ball (world) are still in relationship. As another example, consider what happens when our arm (‘body’) reaches for a cup (the ‘world’) to have a drink: for a brief while we embrace the cup as part of our body. Or consider a young gang member getting the gang's symbol tattooed on his or her arm. Both the tattoo and the gang member's reason for getting tattooed tie their body to their social world. In these ways, through our actions, our bodies – our selves – are seen as being intertwined with the world: we are in the world and the world is in us. As mentioned earlier, Grosz (1994) – drawing on Merleau-Ponty – uses the concept of the Möbius strip to capture this interaction between body and world.

In his last incomplete and tantalisingly mysterious work The Visible and the Invisible, Merleau-Ponty (1968 [1964]) offers a radical reworking of the nature of embodiment. He shifted his focus from embodied consciousness to a notion of intercorporeal being – what he termed flesh. Here, he says, we are connected to others and the world in a double belongingness. The example used by Merleau-Ponty is touching – for instance, our right hand with our left – and the way in which this is always reversible: when one hand is touching (that which is perceiving) then the other is touched (the object of perception) and vice versa. Neither is reducible to the other and both are of the same order of meaning. He draws on the metaphor of ‘chiasm’ – from chiasma, the crossing over of two structures – to show that the world and body are within one another, inextricably intertwined: ‘the world is at the heart of our flesh … once a body-world relationship is recognized, there is a ramification of my body and a ramification of the world and a correspondence between its inside and my outside and my inside and its outside’ (1968 [1964], p. 136). Our embodied subjectivity is never located purely in either being touched or in the act of touching, but in the dynamic intertwining of these two aspects, or where the two lines of a chiasm intersect with one another. Grosz (1994) built on this idea – in her case using the Möbius strip as a visual analogue – to develop a corporeal feminism where the relationship between body and world (individual and social) is fully realised.

The idea of some kind of merging of body and world is counterintuitive and is not an easy one to grasp. The feminist-phenomenologist Iris Young offers the following account of the lived experience of being pregnant, which further elaborates this notion of an intertwining of body and world:

[Pregnancy] challenges the integration of my body experience by rendering fluid the boundary between what is within, myself, and what is outside, separate. I experience my insides as the space of another, yet my own body … [But also] the boundaries of my body are in flux. In pregnancy, I lose the sense of where my body ends and the world begins. The style of bodily existence, such as gait, stance, sense of room I inhabit, which have formed in me as bodily habits, continue to define my body subjectivity. My body itself changes its shape and balance, however, coming into tension with those habits … I move as though I can squeeze around chairs … as I could have seven months before, only to find my way blocked by my own body sticking out in front of me, in a way not me … As I lean over in my chair to tie my shoe, I am surprised by the graze of this hard belly on my thigh. I do not anticipate this touching of my body on itself, for my habits retain the old sense of my boundaries … The belly is other, since I did not expect it there, but since I feel the touch upon it, it is me.