Artwork by Stephen Lee Hodgkins

Artwork by Stephen Lee Hodgkins

The 'social model' of disability

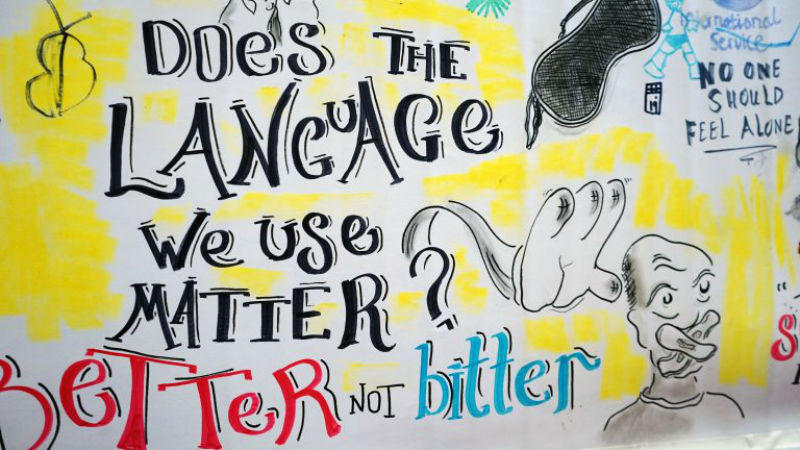

Why does so much doom exist about disability? Where does that come from? The problem is not so much disability rather the idea of 'normal'. Disability is a conceptual anxiety of the normal body and mind. Social and discursive constructive perspectives can help explore the way disability and disabled people are represented in talk and text (i.e., discursive construction).

By focusing on recent and historical texts relating to policy, theory, activism, disclosure, and identity issues, the naturalization and invalidation of the disabled body and mind can be explored and critiqued. Rather than accepting disability as a fixed entity located within the body and mind of individuals, it is possible to argue that it is a discursive object and its construction is linked to historical, social, and political structures.

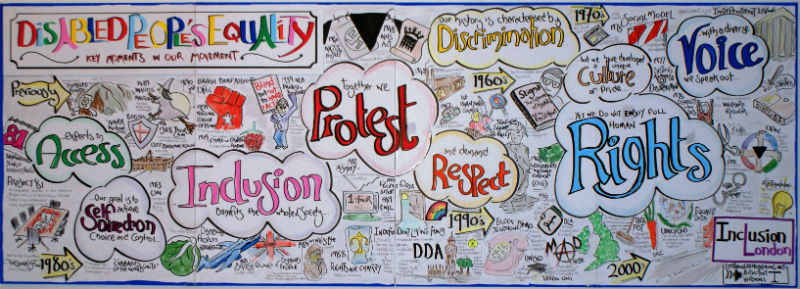

From the 1980s, activists articulated a ‘social model’ of disability. This separates the notion of disability and impairment or condition etc. It asserts people are not disabled by their bodies or minds, rather by the barriers and exclusions they face in everyday lives. These are multiple in form, i.e. environmental, societal, conceptual.

Disabled people have impairments i.e. physical, sensory, learning difficulties, mental health issues, chronic illness etc., but if given the right support and if society were more inclusive, the experience of disability would dissipate. Furthermore, disability is argued as a form of oppression, or socially imposed restriction.

Disabled People's Equality Key moments in our movement by Stephen Lee Hodgkins for Inclusion London

Disabled People's Equality Key moments in our movement by Stephen Lee Hodgkins for Inclusion London

Materialist and Marxist perspectives

In many ways, critical disability studies have been stifled by the dominant view of the disabled body as a natural tragedy, rather than as a matter of political oppression and human diversity. Materialist and Marxist perspectives of disability studies – even though they are opposing mainstream viewpoints – have also appeared reluctant to study contemporary discourse about disability. This reluctance in part relates to much broader contested issues concerning the implications of relativism and social constructionism and the challenges this poses for the radicalization of a social movement.

Specifically, the mobilization of people toward action is perhaps more effectively achieved if their collective identity is easily shared and defined. Research and theoretical work that appears to discredit a disability identity can be easily misinterpreted as denying the inequality facing this group and therefore presents difficulties for the development of a disability movement. Although it is helpful to critique knowledge that legitimates the able body, this type of critique also risks the implication that disability is merely a constructed version of reality that does not exist.

The constructionist approach

A constructionist approach is useful to consider aspects of knowledge, understood through language not as accurate reflections of the of the world but more as an artefact of interaction. In this way, the disabled body and mind is not a permanent state but rather a fluid representation produced through a multiplicity of histories, structures, and discourses.

Disability knowledge and meaning are not then to be taken as an all-encompassing and accurate reflection of the experience of it. Rather, disability should be taken as a social, cultural and discursive representation of it that is actively mobilized and ever reforming in language use.

How we talk about disability, does not so much reflect our understanding of it as so much as offer us versions of it that link to social, political and historical positions of it.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews