Despite strong representation on the pitch, racially minoritised individuals remain underrepresented off it, especially in Europe. This article explores coaching developments across Africa, the Caribbean, and the UK, focusing on the impact of the 2022 World Cup and beyond. It examines whether the rise of indigenous coaches (born in the country, native to the land with family and cultural heritage), signals lasting change or temporary progress and highlights the systemic barriers that still hinder equity. Through this lens, it calls for deeper investment, reform, and a dismantling of colonial legacies in men’s football.

At the 2022 World Cup in Qatar seemingly one powerful narrative was emerging, Africa’s assertion of Black African coaching excellence which could hopefully lead to global conversations about representation, equity, and the dismantling of colonial legacies in football. Since the 2022 World Cup, in the UK racially minoritised coaches are still facing systemic barriers and persistent structural challenges in the quest for true equality in the sport.

Africa's coaching Renaissance: Beyond the World Cup spotlight is it a false dawn?

The historic success of Morocco’s Walid Regragui - the first indigenous African head coach to reach a World Cup semi-final - marked a watershed moment. Cameroon in 1990, Senegal in 2002 and Ghana in 2010 all reached the quarter-finals of the FIFA World Cup but all were coached by White Europeans. Qatar 2022 saw all five African nations led by indigenous coaches, shattering the myth that success required White European expertise. This wasn’t isolated: Aliou Cissé (Senegal head coach) had already secured the 2022 African Cup of Nations (AFCON) title, Rigobert Song (Cameroon head coach) brought unparalleled legacy experience, and Otto Addo (Ghana head coach) orchestrated a World Cup qualification triumph over Nigeria. AFCON 2023 in Ivory Coast finished with the home nation beating Nigeria in the final. Returning to Qatar 2022, I asked the question in my previous opinion piece; was this an ongoing trend or a flash in the pan? Does having indigenous coaches coaching African and Caribbean male football teams indicate progress for racially minoritised coaches in world football? Out of the 24 teams in AFCON 23, nine of the coaches were White, the final would have been contested by two White coaches if Ivory Coast hadn’t sacked their White coach (Jean-Louis Gasset) in the group stages and replaced him with the homegrown Ivorian Emerse Fae after a 4-0 defeat in the group stage. I often watch African and Caribbean teams play and subconsciously compare the quality of the players to European teams and then I ask myself, is the comparison fair when there is not a level playing field between the three continents?

The momentum continues:

- Local success breeding confidence: At the time of writing, in 2025, Morocco’s Regragui remains at the helm, building on his 2022 achievement. Nigeria, previously criticised for appointing Portuguese journeyman José Peseiro, entrusted Finidi George, a Super Eagles legend, with the national team reins after Peseiro’s departure post-AFCON 2023. Nevertheless, George was sacked and replaced in 2025 by Eric Chelle who was one of the indigenous coaches in AFCON ’23 and was the head coach of Mali. This is interesting as one may have expected the next appointment to have been a White European, so the move to appoint a neighbouring African head coach is compelling.

- Structural shifts: The Confederation of African Football (CAF) has intensified its coaching development programmes, explicitly prioritising indigenous expertise. The ‘FIFA Talent Development Scheme’ led by former Arsenal FC manager Arsène Wenger, while promising, faces significant hurdles. As critically noted, its effectiveness is hampered by financial disparities: ‘The barrier... is that the cost of the courses is based on the financial resources of the organising member association,’ (FIFA, 1999), (Mazars & ASCI, 2021) a system inherently disadvantaging African and Caribbean federations compared to their European counterparts.

- Pipeline development: Initiatives like Madalitso Mkoloma’s International Football Heritage Agency (IFHA) are crucial. Mkoloma is an ex-international player of Barbadian heritage and is a youth coach and scout at an English Football League (EFL) club in London. Originally focused on player identification for the Caribbean diaspora, IFHA now explicitly extends opportunities to coaches, facilitating pathways previously blocked by geography or resource limitations. This aligns with former Chelsea FC and Ivorian player Didier Drogba’s long-standing advocacy: ‘African and Caribbean football associations must invest in human capital to be more successful.’(Mazars & ASCI, 2021)

Yet, sustainability concerns linger. As Fadoju (2022) cautioned, it remains unclear whether this shift in recruiting indigenous coaches stems from a genuine ‘informed initiative’, organic evolution, or mere economic necessity. The risk of regression persists, especially for nations facing instability, economic hardship and financial mismanagement in their football associations. The true legacy of Qatar 2022 for Africa hinges on robust, FIFA and CAF-supported pipelines and unwavering commitment from national associations to nurture homegrown talent at all levels from youth academies to senior technical staff. The disparities between income generated by the home nations across the continents indicate that the African and Caribbean associations are lacking behind their European counterparts in investing in training facilities, coaching development, medical facilities and other key areas. Even when there is an influx of aid, grants and financial support from FIFA, corruption and poor planning have led to ineffective investment.

One example is the Nigerian Football Association continuing to misappropriate the funds allocated to them (Busari, 2019; Ofekun, 2024; Okeleji, 2019; Yekeen, 2024). Two key examples are the indigenous coaches for national teams are never paid the same rate as the foreign coaches, furthermore the indigenous coaches’ salaries are always delayed. As it stands now the Nigerian Football Association does not have the equivalent of St George’s Park training facilities that are available to the England national football teams. Nevertheless, this does not cover the main issue which is there is not an effective pipeline for racially minoritised coaches who are qualified to coach in the top teams in Europe and the UK.

In England less than five per cent of professional football coaches in the top four divisions are Black. Societal and racial structures are hampering the progress of Black coaches in the UK (Duffey, 2018).

The Caribbean: Fragile progress amidst persistent challenges

The Caribbean’s journey is more nuanced. While nations like Curaçao (Remko Bicentini), Haiti (Jean-Jacques Pierre), and Trinidad & Tobago (Angus Eve) are led by indigenous coaches, the reliance on White European expertise remains pronounced. Jamaica’s appointment of Icelandic coach Heimir Hallgrímsson in 2022 and more recently Steve McClaren (ex-head coach of England) exemplifies this tension, despite a history of successful indigenous coaches like Theodore Whitmore (pictured below).

Positive signals exist:

- Diaspora engagement: Figures like Emerson Boyce (Technical Director, Barbados), Gifton Noel-Williams (Technical Director, Grenada) and Maurice Lowe (Technical Director, Bermuda) highlight a trend of leveraging diaspora expertise. Their roles signify a conscious effort to bridge the gap between European-based experience and local development needs.

- Grassroots focus: The Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) has increased investment in coach education at youth levels, recognising that sustainable senior success starts with foundational development. However, as noted, comprehensive data on Caribbean coaching demographics remains frustratingly scarce due to limited reporting from federations.

The key challenge, mirroring Africa, is institutionalising this progress. Without significant, sustained investment from FIFA and CONCACAF specifically targeted at coach education and creating viable domestic career paths, the Caribbean risks remaining a talent exporter rather than a self-sustaining football ecosystem. The economic realities are stark, demanding tailored financial mechanisms within FIFA’s development programmes.

The UK’s racially minoritised coaching battle: Targets, tokenism and the fight for substance

The UK landscape, vividly portrayed in Fadoju (2020, 2022) presents a different but interconnected struggle. The statistics remain damning, despite Black players constituting over 30% of Premier League squads, only 5% of managers across England’s top four divisions are from Black backgrounds (Szymanski, (2022). The experiences of systemic barriers from lack of opportunity and covert discrimination to the ‘glass ceiling’ preventing progression resonate deeply.

Recent initiatives offer cautious hope:

- The FA’s 30% target: The most significant development is the Football Association’s (FA) bold commitment: ‘The FA wants England men’s coaching staff to be 30 per cent Black, Asian, mixed or other ethnic background by 2028’ (Sky Sports, BBC Sport). This applies specifically to coaching staff supporting the senior men’s national team and development pathway teams (U15s to U21s). This quantifiable target directly addresses the chronic underrepresentation highlighted in the original article.

- Enhanced diversity code: The FA’s revamped Football Leadership Diversity Code (FLDC) has seen increased signatories from clubs and expanded targets beyond senior coaching to include broader leadership roles (BBC Sport). While not mandatory, it creates pressure for transparency and accountability.

- Rooney Rule implementation: The EFL mandates clubs interview at least one qualified racially minoritised candidate for first-team managerial vacancies. This policy, inspired by the National Football League (NFL), aimed to disrupt unconscious bias in recruitment. However, the initial impact of the Rooney Rule albeit good, has plateaued and it could be better when you compare the percentage of Black coaches in the NFL and the NBA. The NBA had 15 Black head coaches in the 2022/23 season representing 43% of all head coaches in comparison to the NFL 9% of head coaches were Black (Yahoo Sports, 2025). Additionally, in the 2023-2024 NBA season, 11 out of 30 teams (36.7%) had Black head coaches. In the NFL, the figure was lower, with 3 out of 32 teams (9.4%) having Black head coaches at the start of the 2024 season. For the 2024-2025 NBA season, 15 out of 30 teams (50%) had Black head coaches, while the NFL saw a decrease to 3 out of 32 (9.4%). (The conversation, 2025) (ESPN, 2025). Nonetheless, the NBA has always been seen as a progressive organisation and does not have the equivalent of the ‘Rooney Rule’. Would the equivalent of a Rooney Rule be impactful here in the UK? Indications suggest it will not resolve the issues based on the following story FA diversity code ‘made no difference’ in helping Black players get jobs in football (Ferdinand, 2022). Grassroots Focus: Efforts are extending downward. Initiatives like those highlighted by the Oxfordshire FA who recently appointed Eddie Odhiambo to their board of directors in 2024.

Persistent Challenges and Criticisms:

Despite these steps, deep-seated issues remain:

- Tokenism vs. opportunity: Concerns persist that interviews under schemes like the Rooney Rule can be tokenistic if not accompanied by a genuine commitment to appointment and support. Initiatives like the FA’s targets don’t directly solve these complex social issues.

- Lack of senior leadership: Although it is complicated to provide a precise, definitive number of UK football clubs owned by racially minoritised organisations or individuals. This is most likely because many clubs have complex ownership structures (e.g., trusts, partnerships, private entities) that can make it difficult to determine who ultimately owns the club or if a racially minoritised individual or organisation holds a significant stake. Hence a lack of racially minoritised club owners, CEOs, or board members across football means decision-making power remains concentrated, hindering truly transformative change. The ‘old boys’ network that still favours white former players like Wayne Rooney, Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard over their equally qualified racially minoritised colleagues shows no evidence of it being rectified to ensure equity.

Interconnected Struggles, Shared Solutions

The parallels between the African, Caribbean and UK contexts are striking:

- Pipeline development: (I) The UK suffers from a chronic lack of progression for racially minoritised coaches even though there are structured pathways to enable coaches to progress from the grassroots to the professional game. One idea the English FA could investigate is reciprocal mentorship; this would be two coaches (White and racially minoritised) working together through a mentoring process in which they both take on the roles of mentor. (II) Africa and the Caribbean struggles with resource constraints; FIFA, CAF, CONCACAF and The FA must provide effective and sustainable investment in these regions and seek accountability from CAF and CONCACAF (read point 5 below).

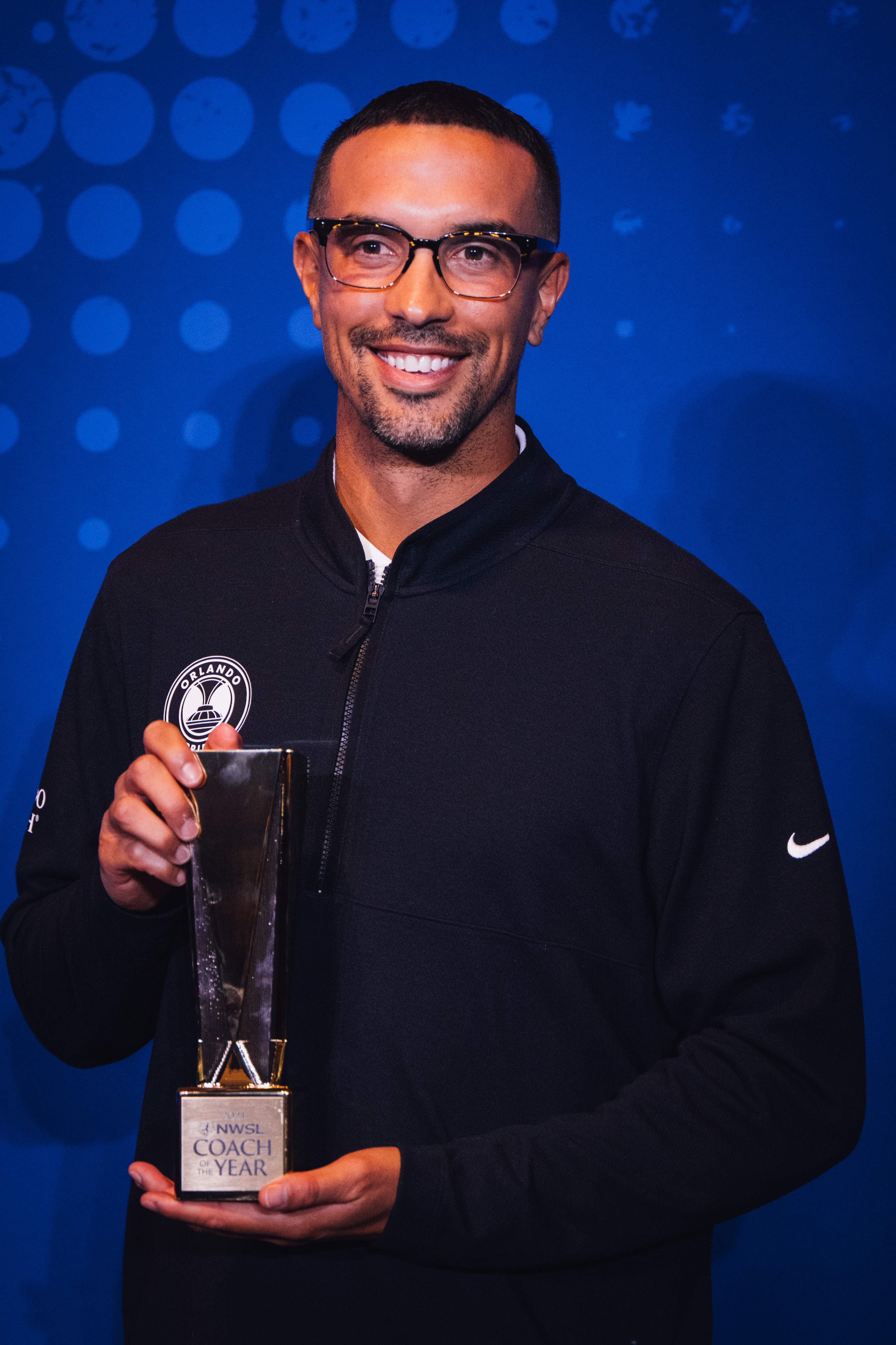

Challenging colonial mindset: Both contexts grapple with the lingering perception that expertise is inherently ‘European’ or ‘white’. Africa counters this by proving local tactical acumen (Regragui, Cissé). The UK must actively dismantle unconscious bias through education, diverse recruitment panels, and celebrating racially minoritised coaching successes. E.g., Englishman Seb Hines (pictured right) was the first Black manager to win a trophy in the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) with Orlando Pride.

Challenging colonial mindset: Both contexts grapple with the lingering perception that expertise is inherently ‘European’ or ‘white’. Africa counters this by proving local tactical acumen (Regragui, Cissé). The UK must actively dismantle unconscious bias through education, diverse recruitment panels, and celebrating racially minoritised coaching successes. E.g., Englishman Seb Hines (pictured right) was the first Black manager to win a trophy in the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) with Orlando Pride.- The role of governing bodies: FIFA and the FA hold immense power. FIFA must move beyond generic development programmes to offer equitable, needs-based funding for coach education in Africa/Caribbean. The FA’s 30% target is commendable but must be part of a holistic strategy tackling barriers at all levels of the English game, from grassroots accessibility to boardroom diversity.

- Diaspora as a resource: Africa and the Caribbean would benefit from engaging their diasporas. African/Caribbean federations should work collaboratively with ex-players and coaches based in Europe for knowledge transfer. The UK’s and Europe’s racially minoritised community, including highly qualified coaches and administrators within it, represents an underutilised resource that CAF and CONCACAF must actively recruit, develop, and promote.

- Accountability and data: CAF and CONCACAF both lack comprehensive data tracking progress. The UK FA’s Football Leadership Diversity Code (FLDC) improves transparency, but independent monitoring and clear consequences for non-compliance are needed.

The road ahead: From targets to transformation

The FA's 30% target for England coaching staff by 2028 is a necessary and welcome benchmark. However, it is merely a starting point. True progress demands:

- Embedding EDI in governance: As piloted by county FAs like Oxfordshire, diversity and inclusion must be core strategic objectives, not add-ons, for all football governing bodies and clubs globally.

- Holistic pipeline investment: FIFA must reform its development funding to prioritise equitable access to coaching education for African and Caribbean associations. The FA must significantly increase investment in identifying, supporting, and fast-tracking racially minoritised coaching talent throughout the English football pyramid, not just the national setup.

- Confronting socio-economic barriers: Addressing the grassroots participation crisis for racially minoritised communities requires partnership beyond football – involving government, education, and transport authorities to tackle issues like facility access, cost, and safety. For example, various UK governments have tried to implement a football regulation bill with no success although it was reintroduced in 2024 Summer’s King’s Speech following the Labour Party’s election victory.

- Mentorship and sponsorship: Formal programmes linking experienced (including white ally) managers and administrators with aspiring racially minoritised coaches and executives are crucial for breaking down isolation and providing advocacy.

- Challenging bias relentlessly: Continuous education on racial bias for decision-makers (owners, CEOs, sporting directors, FA officials) is non-negotiable. Recruitment processes must be audited for fairness. Black players account for 43% of all those playing in the Premier League and 34% of all EFL players (Szymanski, 2022). Yet, in England less than five per cent of professional football coaches in the top four divisions are Black. Societal and racial structures are hampering the progress of Black coaches in the UK (Duffey, 2018). The mythologies or misconceptions that have been around since the 60s - for example Black players can’t play in the cold and Black players cannot be successful leaders - are clearly holding back the progress of Black coaches. As of the 2023-24 campaign, there have been a total of just 11 Black managers in the history of the Premier League. (Goal, 2023).

Conclusion

The legacy of Qatar 2022 for African coaching and the ongoing fight for equity in UK sport are two fronts in the same global battle. Walid Regragui’s success and the FA’s 30% target are significant milestones, but they are not endpoints. They illuminate the path forward while highlighting the distance still to travel. Progress in Africa and the Caribbean demonstrates that indigenous expertise when given opportunity and investment, can excel on the world’s biggest stage. The UK’s initiatives, while nascent, acknowledge systemic failures and set measurable goals. The challenge now is converting these sparks of progress into a sustained flame of transformation. This requires unwavering commitment from federations like FIFA and the FA, courageous leadership within clubs and associations, and a continued global demand for football that truly reflects the diversity of those who play and love the game. Only then will the positive legacies of moments like Qatar 2022 be fully realised, not as flashes in the pan, but as the foundation of a more equitable and representative future for global football.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews