“I awake in bed … In the corner of the room there are two men. I cannot see them but I know that they are there, and what they look like. I can hear them talking. They are talking about murder. I cannot move. One of the men comes and stands directly above me … He spits, and his spit lands in the socket of my closed eye. I can feel the impact, the wetness, the trail of slime.”

This may sound like a scene from the X-Files, but it is actually a personal account of a real experience – told as part of a project on sleep paralysis. This is an unusual condition where one wakes up in the night, unable to move, and often experiences a wide range of bizarre and terrifying hallucinations.

On October 9 a new documentary, The Nightmare, directed by Rodney Ascher, is being released in the UK. The film tracks eight people’s experiences of sleep paralysis, brilliantly recreating their terrifying visions on screen. However, it does not touch on the increasing amount of scientific study into the condition. This is a shame, as researchers are slowly getting closer to unravelling its mystery.

The Nightmare by Johann Heinrich Fussli

The Nightmare by Johann Heinrich Fussli

Hallucinations and risk factors

Sleep paralysis episodes typically occur either early in the night, as someone is falling asleep, or towards the end of the night, as someone is waking up.

There are three categories of hallucinations. Intruder hallucinations consist of a sense of evil presence in the room, which can also manifest into hyper realistic multisensory hallucinations of an actual intruder. Incubus hallucinations often co-occur with intruder hallucinations, and describe a sensation of pressure on the chest and feelings of being suffocated.

The third category include so-called vestibular-motor hallucinations, which typically don’t occur with the other two, and consist of “illusory movement experiences” such as floating above the bed.

Sleep paralysis is more common than you may think. In a recent UK study, nearly 30% of respondents said that they had experienced at least one episode of sleep paralysis in their lifetime. A smaller percentage, around 8% of the 862 participants, reported more frequent episodes. A systematic review of over 30 studies from a variety of countries reported a more conservative estimate, of around 10%.

Sleep paralysis is a common symptom of narcolepsy, a sleep disorder where the brain’s ability to regulate a normal sleep-wake cycle becomes disrupted. It also appears to be more common in a number of psychiatric conditions, particular post-traumatic stress disorder, and patients with panic disorder.

But many individuals suffer from sleep paralysis without any apparent psychiatric or neurological condition. In a recent study, we looked at potential risk factors and found that stressful life events, anxiety, and sleep quality all had an impact. This is supported by other studies showing that groups of people who experience disrupted and irregular sleep, such as shift workers, are at a higher risk of sleep paralysis.

We also looked at the role of genetics, by comparing the frequency of sleep paralysis in identical twins, who share almost 100% of their genes, with the occurrence in non-identical twins, who on average share about 50% of their genes. We found that there was indeed a genetic link. Our research even suggested that a particular variation in a gene involved in the regulation of our sleep wake cycle may be associated with sleep paralysis. But more studies are needed to confirm this.

Laboratory studies

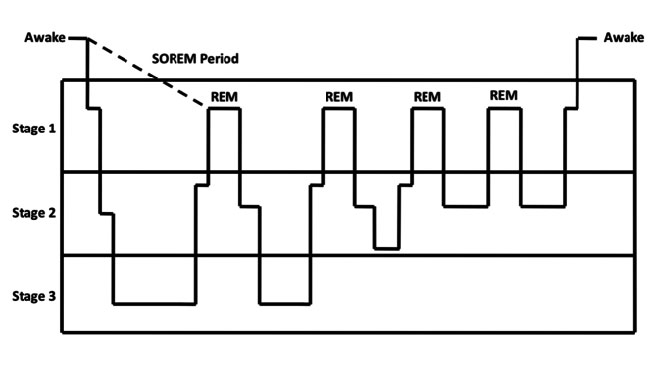

Every night, we pass through a number of different sleep stages (see figure below). After falling asleep, we pass through stages one to three, reflecting a deepening level of unconsciousness, known collectively as non-REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. After coming back to stage one sleep we enter a period of rapid eye movement sleep, which is unique for a number of reasons.

Sleep cycle

Sleep cycle

REM sleep is a period of heightened brain activity, associated with vivid dreaming. During REM sleep our muscles are completely paralysed (apart from the eyes and respiratory system). It is assumed that this paralysis mechanism is in place to stop us acting out our dreams, based on rare cases where the paralysis fails – and patients physically act out the contents of their dreams.

A team of Japanese researchers were recently able to induce episodes of sleep paralysis by systematically depriving participants of REM sleep. They found that if they interrupted enough periods of REM, the sleepers would eventually enter sudden-onset REM (SOREM), which is where one falls straight into REM sleep from waking, bypassing the other sleep stages (this is indicated by the dotted line in the figure). It was found that following these SOREM periods, participants were more likely to have an episode of sleep paralysis – backing up previous studies showing that disrupted sleep increases the risk.

These studies also tell us that sleep paralysis is closely tied to REM sleep. What appears to be happening in sleep paralysis is you wake up and become consciously aware of your surroundings while still in a state of REM sleep, meaning your muscles are paralysed. It could be said that your mind wakes up but your body doesn’t.

Recordings of brain activity during sleep paralysis show it to be a unique state of consciousness. A recent study showed that a participant’s brain activity during sleep paralysis was indistinguishable from a brain recording created by combining a recording from when they were awake, and when they were in REM sleep.

Unfortunately, to date there have been no systematic trials investigating possible medical treatments for sleep paralysis though antidepressants may be prescribed in some severe cases. However, research certainly suggests that trying to maintain a healthy, regular sleep pattern would be a good strategy for trying to reduce the frequency of episodes.

Anecdotal evidence also hints at a number of possible prevention strategies –including changing sleeping position, adjusting sleeping patterns and improving diet and exercise. In a study that asked people who were using such a strategy how successful it was, 79% believed it worked. Another approach is to try to disrupt episodes rather than prevent them by attempting to move body parts such as a finger, or trying to relax. Of people who try to disrupt episodes, 54% believed them to be effective.

While sleep paralysis can be a terrifying ordeal to go through, those who do experience it should try to remember that it is a temporary and harmless event. What’s more, help may be on the way. As researchers are slowing learning more about what causes the condition, chances are that effective treatment may one day be possible.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews