Charles Dickens died of a stroke on June 9, 1870, aged 58 years

Charles Dickens died of a stroke on June 9, 1870, aged 58 years

One in every six people will experience a stroke during their lifetime. And by the time you have read this article, it’s likely that someone in Australia will have experienced one. Stroke kills more women than breast cancer and more men than prostate cancer yet you’re unlikely to read much about it.

There are lots of common misconceptions in the community of what a stroke actually is, how to recognise if someone is having one, and the treatments that improve stroke survivors’ outcomes.

There are new treatments available for stroke; however these are time dependant. So it’s important for the person having a stroke to get to hospital quickly. These time critical therapies often heavily rely on people recognising stroke quickly, and acting quickly to get emergency medical care.

What is stroke?

A stroke can be simply described as an attack on the brain. There are two main types. “Ischaemic” and “haemmorhagic” stroke. Ischaemic stroke is often caused by a blockage in one of the vessels that supplies the brain with oxygenated blood, which eventually causes cell death in the area of brain affected.

Haemmorrhagic is a bleed into the brain. This is often caused by high blood pressure, which causes a weakening of the end of the vessel wall, causing this to burst and bleeding to occur into the brain.

Why does it happen?

There are a number of reasons stroke occurs and a number of well established risk factors. Some of these you can change (modifiable), and others you can’t (non-modifiable).

Stroke is more common in men than women and as you get older your risk of stroke increases. While stroke is not hereditary, having a family history of stroke increases your risk. These are known as non-modifiable risks.

There are a range of medical conditions that increase a person’s risk. These include atrial fibrillation (the most common heart rhythm disorder), high blood pressure, diabetes, a previous stroke or mini-stroke, and high cholesterol.

It’s important you are aware you have one of these conditions and it’s managed appropriately by your healthcare team, to minimise your stroke risk.

Lifestyle factors are things that can often be changed. Smoking, over-consuming alcohol, being overweight and or obese, and being physically inactive, along with excessive salt consumption (which can lead to high blood pressure), are all lifestyle-related risk factors that can be modified.

How do you recognise it?

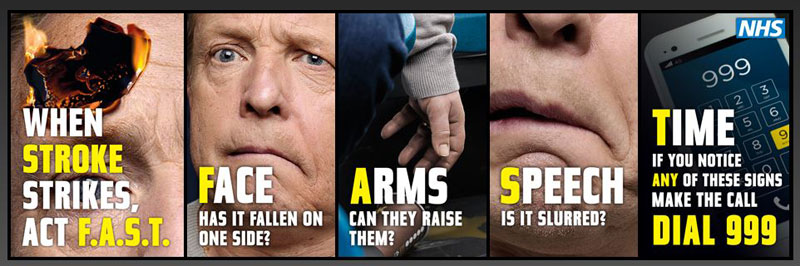

The Stroke Foundation [and the NHS in the UK] have an easy-to-remember acronym called FAST.

Other signs of stroke might include weakness, difficulty speaking, dizziness, loss of vision or blurred vision, headache or difficulty swallowing.

How do you treat a stroke?

Care for strokes varies widely across the country (state to territory, metropolitan to regional), even before you get to the hospital. However, the Australian Acute Stroke Care Clinical Standards outline the care that should be offered to you or a loved one if they were to have a stroke. [Editor's note: In the UK, NICE publish the standards of treatment]

These standards describe the care that may be offered within the health care setting, and support individuals to make informed treatment decisions in partnership with their doctor.

Early assessment will likely include a number of diagnostic tests and scans. The purpose of these tests is to establish a diagnosis of stroke and which type, and tailor treatment based on this.

Other tests are important to establish a possible cause of the stroke. Sometimes, this may have come from a clot in the heart, or a cholesterol plaque dislodged from a neck vessel that supplies the brain with oxygenated blood. Sometimes these clots can travel up to the brain, and lodge within a vessel in the brain, causing the stroke.

Time-critical treatments include treatments to dissolve or remove the clot in ischaemic stroke. Not all patients are eligible for this, and there are strict criteria someone must meet to have these therapies.

To optimise eligibility for these, it’s important to get to hospital quickly. Retrieving the clot needs to happen within 4.5 hours of onset of signs and symptoms of stroke and this includes all the time in hospital for scans and blood tests. After this time, often the risk of these therapies outweigh the potential benefits.

Stroke patients ought to be cared for in an organised stroke unit. There is strong evidence to demonstrate people who get admitted to these units, and are cared for by nurses and doctors that specialise in stroke care, have better outcomes.

If your loved one is not being cared for in one of these specialised stroke units, ask why. Patients and their family members should be informed care would be better elsewhere if they’re not being cared for in a dedicated stroke unit, and be provided with options to transfer to a specialised unit.

In hospital, patients can expect to be cared for by doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, dietitians, psychologists, and case managers who all specialise in stroke care. This team will ensure you’re discharged from hospital with the correct medications to help reduce your risk of a second stroke and will provide advice around exercise, mobility, diet and managing your psychological well-being.

Transition from hospital can be a time of extreme vulnerability for many who survive stroke. Leaving hospital may include a period of inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation, transfer home with some additional support and services, or transfer to nursing home, or residential aged care.

In Australia, stroke has been a national health priority since 1996. However, over these last two decades has not received any federal funding commitment from successive governments. With the emergence of new therapies to treat stroke, it’s important Australia has an agile and responsive healthcare system to adapt to innovations in treatment.

For more information, visit The Stroke Assocation or NHS Choices BUT IN AN EMERGENCY CALL 999

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

2 types of strokes. (Isch, And Bleed in the brain).

4.5 hours after a stroke to get proper treatment.