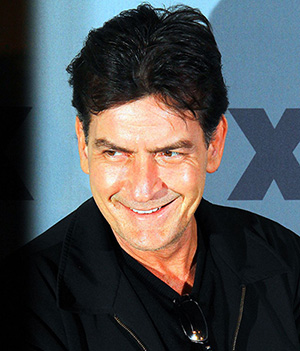

Charlie Sheen’s disclosure that he is HIV positive echoes a similar announcement made by another movie star, Rock Hudson 30 years earlier – and it’s interesting to compare the two cases.

Charlie Sheen’s disclosure that he is HIV positive echoes a similar announcement made by another movie star, Rock Hudson 30 years earlier – and it’s interesting to compare the two cases.

Both tried unsuccessfully to conceal their HIV status. Hudson was betrayed by his appearance: he was visibly unwell and his disclosure came just a few months before his death. Sheen appears, and is, healthy, but he says that he was being blackmailed – and his need for secrecy and his vulnerability to extortion suggests that HIV stigma remains strong.

So what changed between 1985 and 2015?

Well, HIV has changed immeasurably, thanks mainly to the development of effective pharmacological treatments. If Rock Hudson were diagnosed today, he could reasonably look forward to a healthy life expectancy. He might also expect to be non-infectious. Sheen’s use of the word “undetectable” has done much to alert non-specialist audiences to the transformations taking place in the lives of people with HIV.

Of the roughly people with diagnosed HIV in the UK, for example, 95% are having regular blood tests to measure levels of the virus. Of those, 90% are on treatments, and 90% of them are “virally suppressed” or “undetectable”. This means that for the majority of people with diagnosed HIV in the UK: (a) their disease progression has been essentially halted and (b) they are functionally non-infectious, that is to say it would be very difficult for them to pass on HIV to their sexual partners. The challenge for public health now is to get the estimated 6,600 people who have undiagnosed HIV infection to come forward for testing.

Changing times

HIV stigma has come a long way, too. Perhaps it was because the symptoms of HIV were so visible in the 1980s that those who first wrote about it were cultural theorists such as Sander Gilman and Simon Watney. Recent cinematic histories such as How to Survive a Plague, United in Anger and It's a Sin show us that HIV stigma, and the response to it were messy, political, confrontational and often theatrical.

However, in the intervening decades, the concept of HIV stigma has itself been transformed: HIV stigma has been metricised. Like all diseases, HIV has bio-medical, interpersonal and social/political dimensions. The challenge for public health systems is to formulate effective responses on all three fronts; and to measure effectiveness, we need metrics.

Demonstrating the efficacy of biomedical interventions is relatively straightforward. Likewise, we can measure the effectiveness of interpersonal interventions to improve knowledge and change behaviours. But intervening on the social/political level is more complicated.

Consensus in the early 2000s that HIV stigma compromises both the health of people with HIV and HIV prevention efforts led to the establishment of global targets for the reduction of stigma and the proliferation of instruments to measure stigma. Thus, HIV stigma has emerged as pretty much the only ‘social’ metric used by public health systems to measure the effectiveness of responses to HIV.

While no one would argue that HIV stigma presents a major barrier to HIV treatment and care, this “metricisation” proposes a simplified construction of stigma: as something bad that “society” does to people with HIV or as something to be eradicated by interventions.

The work of Foucault and Goffman and – in relation to HIV – Richard Parker, however, reminds us of richer constructions of stigma; of stigma as it works on, between and within different groups to regulate behaviours and preserve or undermine existing power balances.

Why stigma is here to stay

Our own work shows the ways in which people with HIV are affected by stigma but also how they as individuals and groups are constrained to use stigma to maintain group and individual difference. Stigma is productive: for better or worse, it can’t be eradicated because it is an integral part of the way we work as a society.

This allows us to think about how HIV stigma has changed over the decades. In the early days, HIV infection itself was stigmatised: all people with HIV were the subject of moral condemnation. Later, a distinction arose between the “innocent victims” of HIV (those infected through blood products or in utero) and those who had “brought it on themselves” through their lifestyle: gay men, sex workers and people who use drugs.

‘Bad’ ways of living

However, more recently, the focus of stigma seems to be shifting away from how you contracted HIV infection and towards how you live with HIV. HIV stigma perpetuates ideas that there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ ways of living with HIV.

The “good” way is to be responsible: to take medications properly and look after yourself. Preferably one should be undetectable and should disclose one’s HIV status to all partners. The “bad” way is to be irresponsible: to be sexually promiscuous, inject drugs, be a sex worker, to not adhere to medications, to be unhealthy and probably have a detectable viral load.

Thus we see that in the same breath that he discloses his HIV status, Sheen distances himself from these aspects of “bad” HIV: he uses a lot of recreational drugs but he was never involved with “needles and that whole mess”; he had a lot of sexual partners, but he “always led with condoms and honesty”; he hired sex workers whom he is quick to describe as “unsavoury and insipid types”. Above all, he is under medical supervision – he presents his doctor in person on the Today show who verifies that he is “undetectable”.

HIV stigma presents those of us involved in public health with a dilemma. Stigma serves to perpetuate highly normative yet highly desirable (in public health terms) behaviours and attitudes: personal responsibility, treatment compliance, a healthy lifestyle etc. However it also demonises those deemed “irresponsible”: those people with HIV who, for whatever reason, cannot or will not adopt different behaviour. HIV stigma is simultaneously productive and divisive and that makes us very uncomfortable indeed.![]()

This article has now been updated since it was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews