Find out more about The Open University's Psychology courses and qualifications

Psychological contract

When we go to work, we have a set of expectations about how and what our employment relationship will be with our employer and colleagues, added to our employment contract. This is what psychologists call a psychological contract (Rousseau and Tijoriwala, 1998). These unwritten expectations form the employer-employee relationship and constantly changes. Based on informal arrangements and mutual beliefs about work, if an employee feels they are being treated fairly and equitably their sense of wellbeing in their job is often high. If there are perceived breaches in this psychological contract e.g. change in work patterns, place of work, feeling under threat or redundancy, this leads to damage in the relationship between employer and employee. Breaches in the psychological contract cause employees to become disengaged, less productive and sometimes workplace deviance will occur.

The grieving process when a job is lost or changed

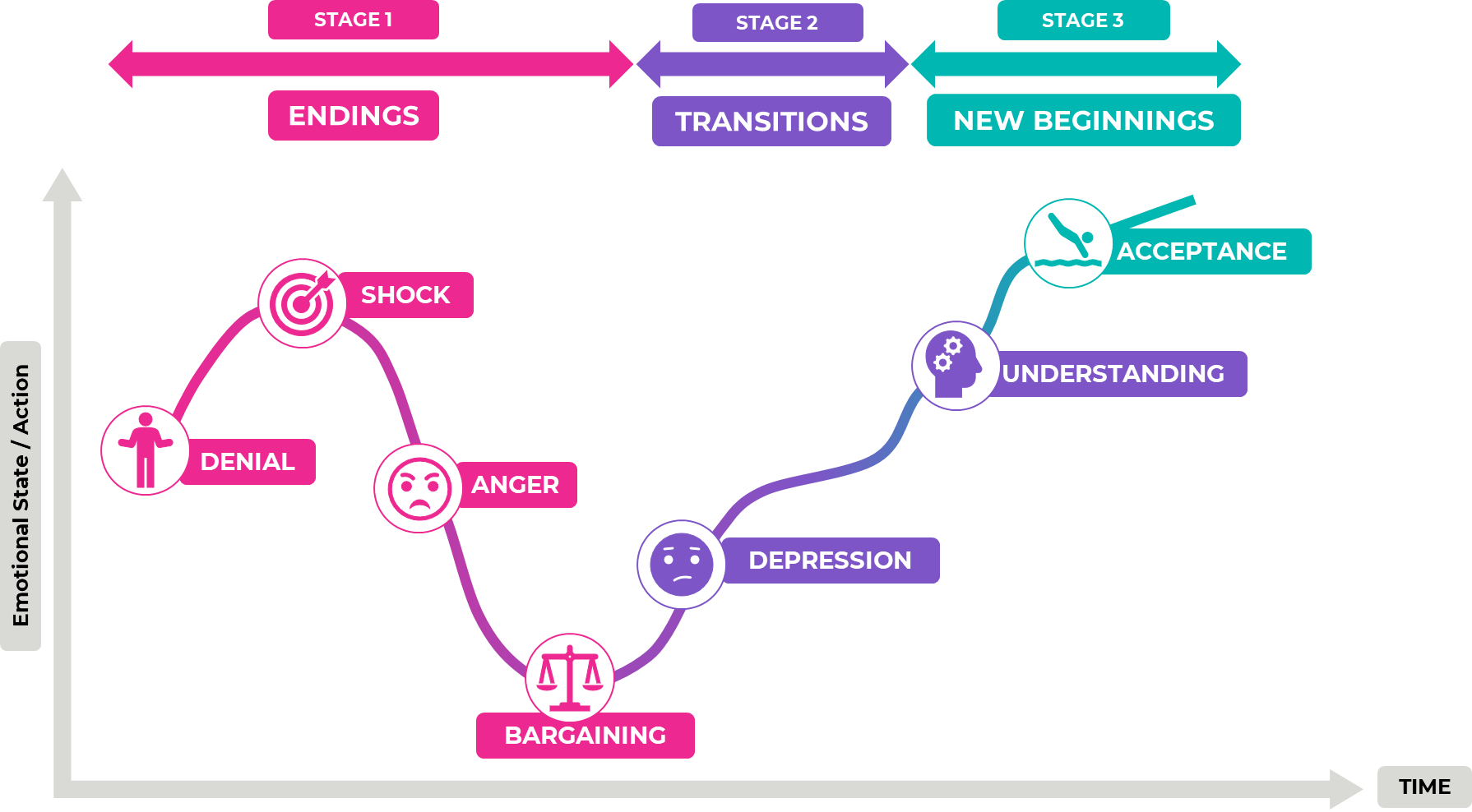

Kubler Ross, a Swiss-American psychiatrist, studied death and experiences of dying while working with terminally ill patients. She identified five stages of grief and loss in her research and found that each individual who went through grief and loss did so at different paces but that the emotional journey was the same for everyone. The loss of work and employment has been seen to follow the same pattern of grief, and has been found to be highly relevant in organisational change and the effects on the workforce.

Five stages of grief and loss

1. Denial: individuals are in shock and disbelieve the situation and are confused.

2. Anger: that this is happening to them, seek to blame, become defensive and resistant to acknowledging the situation.

3. Bargaining: where attempts are made to negotiate about their position.

4. Depression: causing low mood, a feeling of helplessness and sense of being stuck.

5. Acceptance: of the situation when there is an understanding of the inevitable which leads to moving forward.

These stages are standard defence mechanisms humans go through when managing grief and change. Progression to acceptance is different for everyone and there is no set time or consequence moving through these stages of grief. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, many have lost a sense of work identity, self-identity and things are certainly not the same. Aside from the human cost of loss of possibly family and friends, many have had changes and loss within their work environment. This cycle of grief is relevant in managing change in times of uncertainty.

Kubler-Ross’s model has been adapted in change management to explain what journey individuals can take if they are losing their job or having changes made where there is little or no control over the decisions being made.

Fig. 1 Kubler Ross Curve and change

Fig. 1 Kubler Ross Curve and change

When there is a sudden change in circumstance at work, that is outside our control, people often go through a stage of not wanting to talk about it, feeling that therefore denying that anything is going to happen (the ostrich syndrome). If one is in denial, then there is no vision of what can be done and where they may need to go. This is often accompanied by a feeling of shock and seeking confirmation that this is not true. If you know that your organisation is laying people off, or has done, then employees often do not accept the situation and deny that this is happening. This is often aligned with confusion as their future has changed.

If given a shock without warning, an individual can experience high levels of frustration and anger at the changes happening without their own input or control. When individuals feel powerless, unable to reverse decisions or situations, they can become resentful and frustrated and often behave by saying or doing inappropriate things. It is at this time when individuals may start to maximise their communication, be challenging, and trigger a trail of bargaining to try to negotiate their way out of the situation. Often the anger will be focused in the wrong direction, i.e. is misplaced being brought on by fear of the unknown. The bargaining might be in the form of negotiating when they finish work or offer taking a pay cut or reduced working hours, in order to postpone what is happening.

Depression will follow when frustration and utility are not bearing fruit. This is when an employee can feel guilty, helpless and great sadness. This is a key stage where people often keep moving in cycles of anger and bargaining, feeling low. They may develop a lack of interest in their job or work, losing trust in their organisation and perform at a lower level of productivity, or engage in counterproductive behaviour through damage to property and systems.

The final stage of acceptance happens when they can see no more hope, leading to reconciliation with reality. If the individual can be motivated and seek new horizons and experiment at this stage, they will not continue to stay in the negative cycle of frustration, anger and disbelief. The grief that workers can feel, if they accept the situation, then accept and embrace the change, have a less negative effect on their sense of wellbeing.

Those left behind at work

One of the key things that happens to those who retain their job while work colleagues lose theirs is a form of guilt referred to as workplace survivor syndrome. Being one of the ‘lucky ones’ often comes with negative feelings and thoughts. To those who are left behind in the workplace, whilst they have seen many colleagues ‘let go’ then this has psychological impact. This too has its own cycle of grief for the loss of colleagues, the loss of the unknown and fear for some, that they may be next.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews