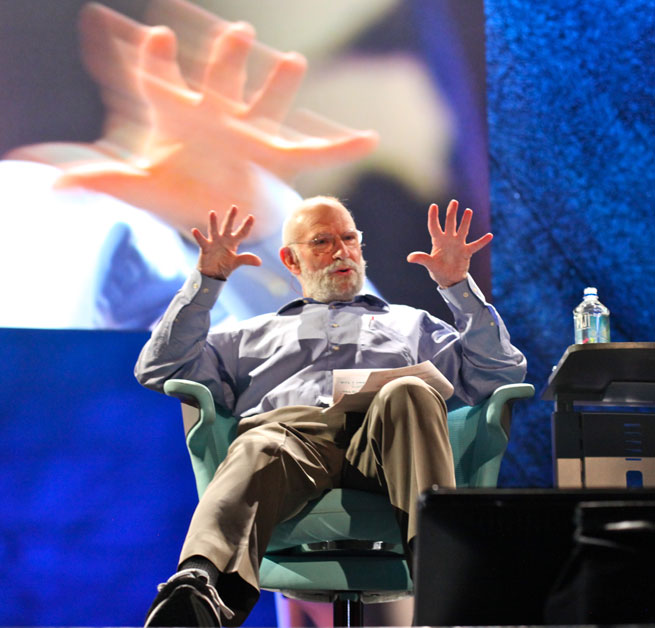

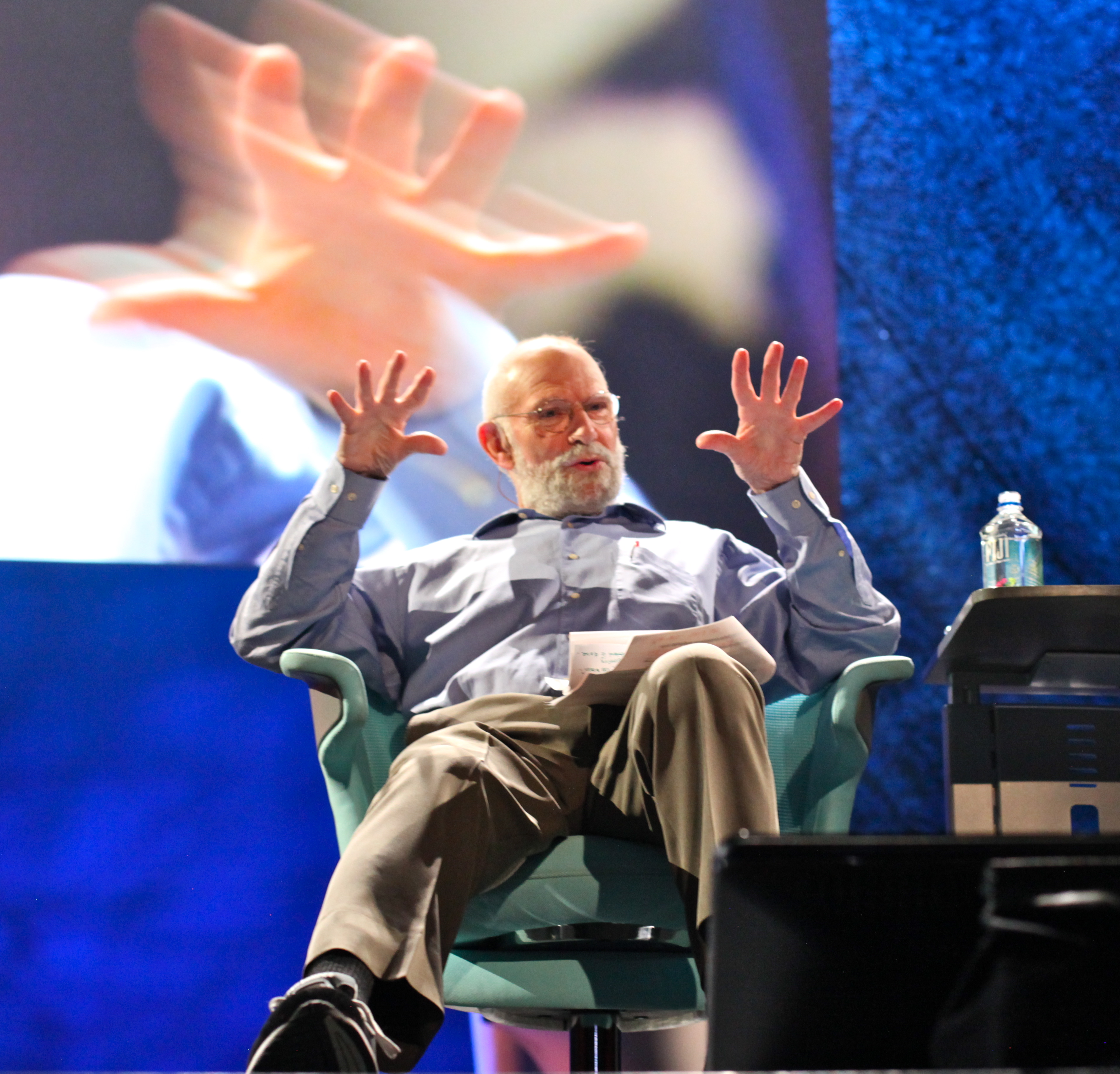

Oliver Sacks died yesterday. He was a neurologist who wrote about his cases. I loved his prose. You could learn a lot from his unornamented style and intriguing titles. When you start reading something he has written, you immediately relax, knowing you are in the hands of a master storyteller. His narrative sweeps you away into another world without drawing attention to itself.

I feel about Dr. Sacks as I do about all great non-fiction writers: I admire at his abilities, I am amazed that his simple prose is so effective, and of course, I am envious. All I want is to do what he does. Is that so much to ask?

Here are a few of his first paragraphs. They are promises, whispered softly and calmly, that something good is coming.

Many of my childhood memories are of metals: these seemed to exert a power on me from the start. They stood out, conspicuous against the heterogenousness of the world, by their shining, gleaming quality, their silveriness, their smoothness and weight. They seemed cool to the touch, and they rang when they were struck. (Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood)

Neurology’s favourite word is ‘deficit’, denoting an impairment or incapacity of neurological function: loss of speech, loss of language, loss of memory, loss of vision, loss of dexterity, loss of identity and myriad other lacks and losses of specific functions (or faculties). For all of these dysfunctions (another favorite term), we have private words of every sort — Aphonia, Aphemia, Aphasia, Alexia, Apraxia, Agnosia, Amnesia, Ataxia — a word for every specific neural or mental function of which patients, through disease, or injury, or failure to develop, may find themselves partly or wholly deprived. (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat)

When I was at boarding school, sent away during the war as a little boy, I had a sense of imprisonment and powerlessness, and I longed for movement and power, ease of movement and superhuman powers. I enjoyed these, briefly, in dreams of flying and, in a different way, when I went horse riding in the village near my school. I loved the power and suppleness of my horse, and I can still evoke its easy and joyous movement, its warmth and sweet, hayey, smell. (On the Move: A Life)

A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out — a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver. Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. The radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye. But though ocular melanomas metastasize in perhaps 50 percent of cases, given the particulars of my own case, the likelihood was much smaller. I am among the unlucky ones. (“My Own Life,” an essay in the New York Times about his own terminal diagnosis)

The everyday writer should not write like this: you need to get right to the point. But I like how Oliver Sacks starts in a matter-of-fact way. If you say that you cannot write in an interesting and straightforward way about your technical field, ask yourself how a neurologist writing about the intricacies of the brain became a bestselling author. He did it because he clearly explained the fascinating content of his field and how it touched people. You can, too.

I do have one strange quality in common with Dr. Sacks. We both have trouble recognizing the faces of people we’ve met before. In this, too, he gives me hope.

This article was originally published at Without Bullshit under a CC-BY-NC licence

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews