4 Power: the medical gaze and the management of risk

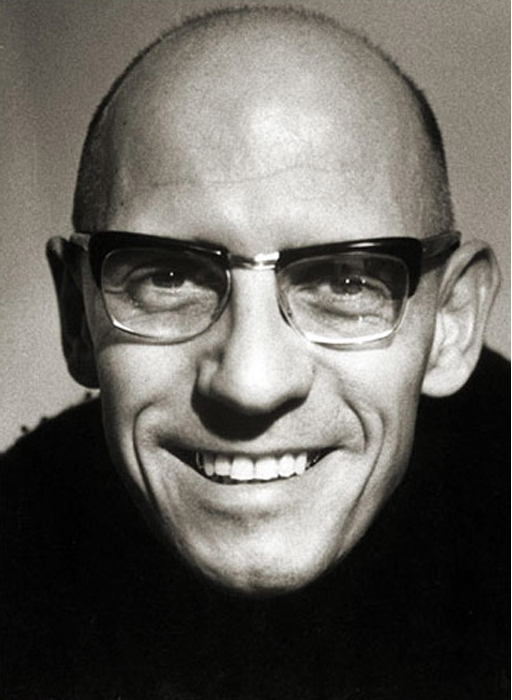

Power is an essential feature of the debate about the medicalisation of death, as western societies value knowledge and expertise and allocate authority accordingly. As highly trained professionals, medical and clinical practitioners fall into some of the most highly esteemed positions of authority in society. The philosopher, Foucault highlights the relationship between power and knowledge. He connects them to the extent that:

[P]ower and knowledge directly imply one another; … there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations.

In claiming that in modern societies power is knowledge, Foucault argues that there are more subtle forms of control than coercion and force. For him, power is everywhere and no one can be outside its influence. Power, according to his theorising, is not possessed but instead is something that can be understood as relational. He sees this relational feature as embedded in social organisations, expressed through hierarchies and determined through discourses.

One of the main criticisms of Foucault’s work is his failure to acknowledge the power of resistance. In their review of professional power, medical sociologists Simon Williams and Michael Calnan suggest that the traditional systems of medical knowledge are being challenged by developments such as mass media, greater access to information and alternative forms of health (and death). They conclude:

In this world of uncertain times, one thing remains clear: namely, that lay people are not simply passive or active, dependent or independent, believers or sceptics. Rather, they are a complex mixture of all of these things (and much more besides).

Challenges to medical power as forms of resistance (i.e. not ‘fitting’ the medical view) might include such things as the use of complementary and alternative medicine; seeking different opinions, including the use of the internet; or refusing to take medical advice. These are all problematic in that they depend on ‘other’ forms of power, many of which can be located within the broad realm of medical knowledge. Foucault’s arguments that discourses shape and produce people's identity do not take people out of the realm of being defined as ‘dying’. Thus resistance here is not convincing. The course authors would therefore argue that the notion of resistance can be viewed as much more subtle. The medical profession might be part of the force that is defining illness and wellness, but individual doctors are not necessarily consciously setting out to do so. Likewise, resistance can be viewed differently. Both dying unexpectedly and not dying when a terminal diagnosis has been given have been seen as forms of resistance. This is not necessarily a matter of conscious choice, but of the inappropriateness or lack of usefulness of the medical diagnosis. On one level, medical definitions of death and dying are literally being resisted. An OU academic has argued that care home staff try to manage the period of dying, despite the reality that the bodies of ageing and frail residents are in a gradual but highly uneven decline into death and resistant to being categorised as either living or dying (Komaromy, 2001). Furthermore, regardless of any definition that might be made about their status, their bodies will continue to deteriorate.