This content is associated with The Open University's Sport and Fitness courses and qualifications.

The Football Association (2019) reports that the success of the England women’s team at the 2015 and 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup has been a key driver for increasing female participation in football at all levels. There are now over 2.5 million registered players in England, with football being the most popular sport for females. On a worldwide scale, FIFA has the strategic goal to increase the level of female participation in football to 60 million players by 2026 (FIFA, 2022). With such a dramatic increase in participation, we might also expect to see an overall increase in the number of female footballers sustaining a knee injury.

In professional football, injuries are quite common due to the high physical demands of regular training and competition. The Football Association Injury and Illness Surveillance Study reported a match injury incidence of 18.5 injuries per 1,000 hours for senior women’s international football players (Sprouse et al., 2020).

An injury to the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) in the knee has received special attention from researchers and the media due to its potential severity and because females are at a higher risk of sustaining the injury (Marmura, Bryant and Getgood, 2021). A study by Montalvo et al. (2019) found that female football players had more than double the incidence rate of an ACL injury relative to male football players. Interestingly, this difference was irrespective of participation level, which suggests that other factors are at play. During the UEFA Women’s Euro 2022, the unfortunate issue of female ACL injuries were in the spotlight again. Even before the tournament started, Spain captain and Ballon d'Or winner Alexia Putellas was ruled out with an ACL injury.

What is an ACL injury?

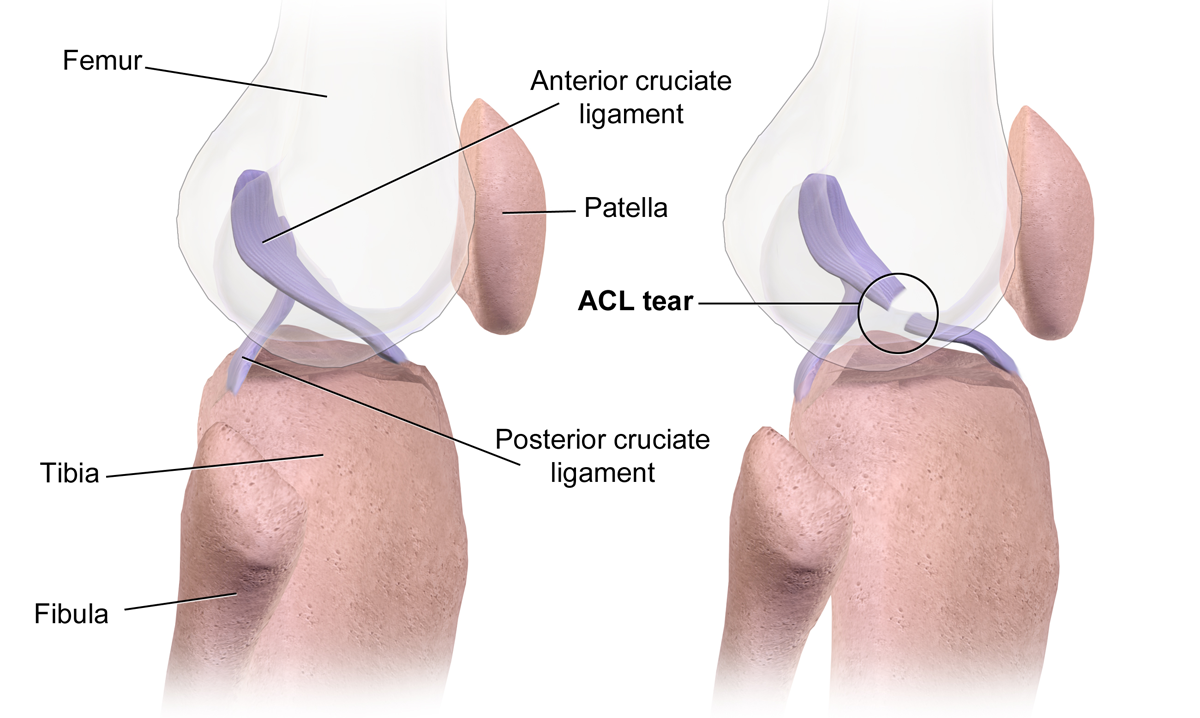

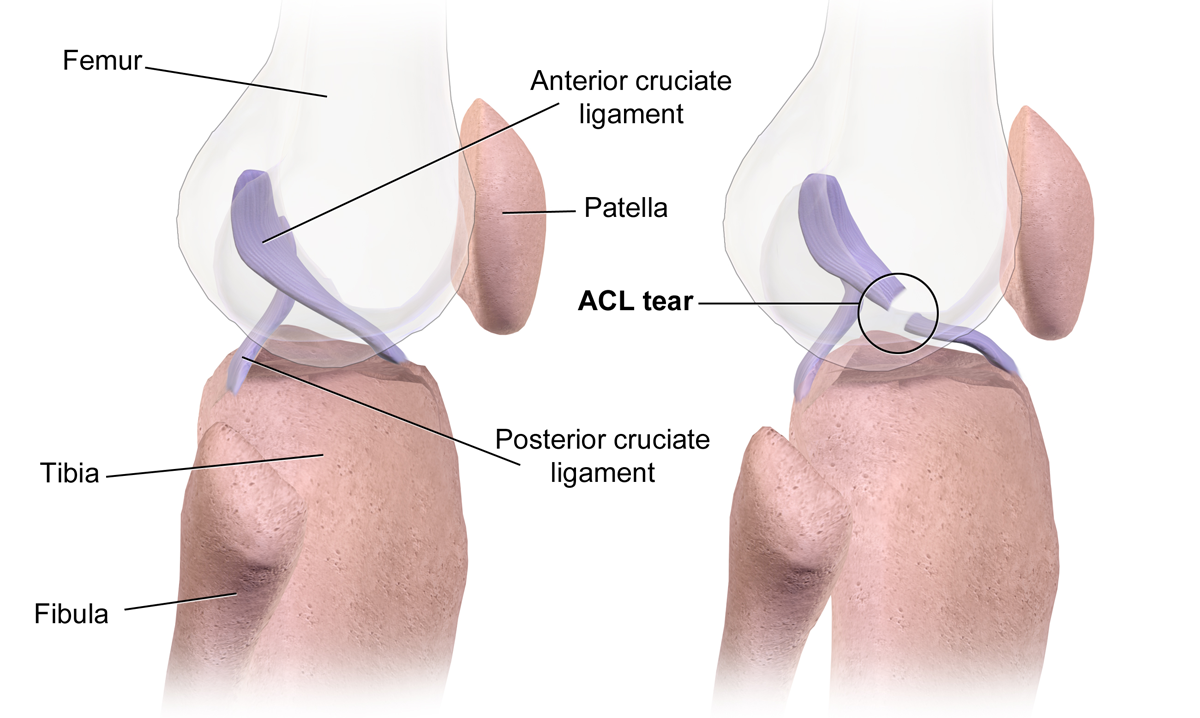

The ACL is a strong band of connective tissue which runs diagonally inside the knee, joining the thigh bone (femur) to the front of the shin bone (tibia). In conjunction with the other ligaments in the knee, such as the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL), it helps to give the knee joint stability.

An ACL injury can involve the ligament being overstretched, partially or completely torn, or a detached from the bone. Therefore, an ACL injury can have different grades of severity and is likely to cause varying degrees of instability, reduced range of movement and difficulty performing certain movements. This has significant implications for professional footballers who would need to have prolonged time out of training and competition for potential reconstructive surgery, recovery and rehabilitation.

Elite female footballers have also reported there is a culture and expectation of overtraining and high levels of pressure to play when not physically or psychologically fit. This can lead to behaviours which might increase the risk of injury.

The issue has been highlighted in the media with reports of professional female footballers who have been put out of action for long periods of time, such as Jordan Nobbs, Aoife Mannion, Abi Harrison and Ellie Brazil (BBC Sport, 2020). Ahead of the 2023 World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, Lionesses stars Leah Williamson and Beth Mead have suffered with ACL injuries, alongside their Arsenal team mate Vivianne Miedema, putting an end to their participation in the tournament.

Unfortunately, some athletes with an ACL injury may not return to their sport, will gain unwanted weight, and develop degenerative knee conditions in the future (Montalvo et al., 2019).

Why are female footballers at more risk?

During maturation, females experience changes that may increase their risk of an ACL injury. This includes the generalised laxity of ligaments, dominance of the quadricep muscle in knee stabilisation and higher turning forces occurring at the knee (Marmura, Bryant and Getgood, 2021). It has been proposed that sex hormones (e.g. relaxin, progestin and oestrogen) may increase the risk of an ACL injury in females because they promote ligament laxity. A study found that general joint laxity is higher in the ovulation phase, around day 14, of the menstrual cycle which may have implications for an ACL injury risk (Shagawa et al., 2021).

An ACL injury in females is often due to non-contact mechanisms relating to movement patterns such as twisting the knee, limited bending of the knee joint, a large amount of hip flexion and moving the body away from a planted foot (Marmura, Bryant and Getgood, 2021). For example, this could occur during a sudden change of direction whilst running or when landing from a jump. This is more likely to occur during the pressure and demands of a match situation than in training (Sprouse et al. 2020).

However, Fox et al. (2020) suggest that a female’s injury risk is not just down to biological causes (e.g. hormones, anatomy, physiology) and is likely to be strongly influenced by what they term ‘gendered environmental disparities’ (i.e. different experiences in sport and less access to training facilities).

The training and competition environments may differ for male and female athletes which could contribute to the occurrence of an ACL injury. For example, women’s teams have often been allocated artificial surfaces or poorer grass surfaces than men, which can increase the ACL injury rates (Braun, Wasterlain and Dragoo, 2013). Elite female footballers have also reported there is a culture and expectation of overtraining and high levels of pressure to play when not physically or psychologically fit. This can lead to behaviours which might increase the risk of injury (Ivarsson et al., 2019).

How can ACL injuries be prevented?

A study by Crossley et al. (2020) found that multicomponent, exercise-based injury prevention programmes led to a 45% reduction in ACL injuries in female footballers. These programmes often include exercise components such as agility, balance, mobility, plyometrics, running and strength activities. Arundale, Silvers‐Granelli and Myklebust (2022) also recommend the use of motor learning principles and video feedback to facilitate changes in biomechanics and movement patterns (i.e. training players to cope with the physical demands and teaching them less risky movement patterns).

An effective ACL injury prevention programme should also consider socio-cultural and psychological perspectives, as well as other non-physical factors (e.g. training environment) which might contribute to an ACL injury. Finally, in light of the vast increase in participation and the high physical demands of the professional game, it is essential that football coaches are educated about the cause and prevention of female ACL injuries.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

I would be inclined to look at the biomechanics of loading forces through the knees as genetically women are more knocked knees (Genuflects Valgum) and therefore increases the stress levels along the joint line of the MCL as well as the Medical condyle / meniscus.

I would be interested in conducting a statistical approach to this article relevant to my country.

Sincerely