7 Detroit Industry

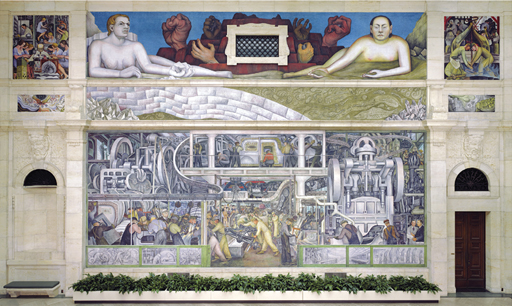

In Detroit Industry (the 27-part mural spanning all four walls of the Garden Court of the Detroit Institute of Arts) the two principal sections focused upon the River Rouge Ford factory at Dearborn, just outside the city. The north and south walls were dominated by the massive Production and Manufacture of Engine and Transmission (Figure 10) and Production of Automobile Exterior and Final Assembly (Figure 11) frescoes respectively. Structured within grid-like compositions indebted to the artist’s earlier Cubist work, they were painted in a social realist mode that foregrounded the fact that the Ford plant was the epitome of industrial modernity at the time (Indych-López, 2016, p. 343).

Rivera, nevertheless, combined this realist emphasis upon the modernity of the factory plant with a focus upon what actually happened on the shop floor. Here Rivera was clear that, even in the most advanced technological plant in the Western world, the role of human labour continued to be central to the processes of industrial production. While there is an actual image of a finished automobile in the distance in the centre of the south wall it is so small as to be barely perceptible. Instead the central foreground is dominated by the image of heroicised automobile workers engaged in performing a multitude of different tasks in assembling the cars that were produced at the Rouge, and this is mirrored in the lower half of the north wall with monumental figures arranged in a frieze-like fashion across the whole wall from left to right while working on one of the many conveyor belts in the factory.

With this dual emphasis upon the industrial modernity of the plant and the heroic labour of the workers, Rivera pulled off something of a coup. The world’s premier political artist had taken the Ford Company’s money – nearly $21,000 – and produced an image of contemporary cutting-edge industrial production that not only pleased its corporate sponsors but also the multi-ethnic workforce that operated the machinery, at least those who had not been forced out of their jobs and deported back to Mexico (Lee, 2005, pp. 211–12). There is, indeed, an image of an overseer in both of the main walls: the green-faced figure to the left of Rivera’s self-portrait with a bowler hat looking out at the viewer in the top left of the north wall and the bespectacled figure with a white hat and suit in the left of the south one. Such details allude to the fact that the Ford Motor Company had a ruthless management culture that readily used a network of spies to intimidate and regulate the workforce (Smith, 1993, p. 54). Yet, other than this, there is little to suggest the capitalist relations of production that actually framed the production process at the plant.

As art historian Anthony Lee puts it: ‘The factory floor is laid out like a blueprint, a manual for alternately a capitalist or a socialist operation’ (Lee, 2005, p. 210). For Rivera, as for other communist thinkers and intellectuals at the time, it was not the forces of production that were the problem – indeed they had the potential to speed up the manufacturing process while minimising the necessary human labour involved – just the model of private ownership under which the factory operated. With this in mind, it could be argued that the two central images of monumentalised purposeful human labour, with workers depicted in a perfectly symbiotic relationship with the machines that they operate, Rivera not only painted a realistic rendering of the workings of the Ford plant but also alluded to a communist vision of an industrial utopia in which the relations of production have been transcended, private property socialised, and the alienation of industrial labour rendered obsolete. This is hinted at by the cultural historian Terry Smith when he claims that here Rivera painted not only an image of modern industry, but ‘its prehistory, its birth, its present structure, and its future’, just as the artist had done in terms of the subject of Mexico itself in his National Palace mural (Smith, 1993, p. 204).

What is really interesting here is how these two main walls fit within the larger iconographic scheme to say something about the present and the past, and the relationship between the United States and Latin America. If this is, as Paul Wood argues, ‘the greatest of all socialist realist projects’ this is because of ‘the connections it draws between modern industry and more distant times and places, and the way it situates modernity in both a history and a geography’ (Wood, 2014, p. 211).

In the upper registers of the two main walls, Rivera depicted the four races that between them comprised the ethnic diversity of the Americas: white, yellow, brown and black, with each one holding a particular mineral essential to the production of iron, which is itself central to the development of industrial modernity. The tracing of this modern manufacturing regime in Detroit back to pre-Columbian times, and the relationship between the two continents, is made most explicit in a painted grisaille detail on the west wall, which represents the interdependence of North and South America (Figure 12).

Here, Rivera painted the freight ships that moved between Detroit, symbolised by the skyline and industrial port on the left, and the Amazon, symbolised by the tropical landscape and rubber plantation workers on the right – what Linda Bank Downs, who has worked extensively on the mural cycle, has argued is a reference to Fordlandia, the Ford Company’s failed attempt to produce its own rubber in the rainforest in Brazil (Downs, 1999, p. 85). Rivera was obsessed with the idea of pan-Americanism and what Wolfe described as ‘a wedding of the industrial proletariat of the North with the peasantry of the South, of the factories of the United States with the raw materials of Latin America’ (Wolfe, 1991 [1963], p. 278). When Rivera painted his mural scheme in Detroit, this relationship was obviously unequal on every level and, as such, Smith sees this pan-American fantasy as hopelessly naive and apolitical (Smith, 1993, p. 213). Yet if this panel is considered in terms of the utopian dynamic of the main murals on the north and south walls, it is possible that this confluence of the waters of Detroit and the Amazon could be encoded with a utopian dimension that points to a possible future when this relationship between the north and the south could be equal.