8 The Rockefeller Center mural

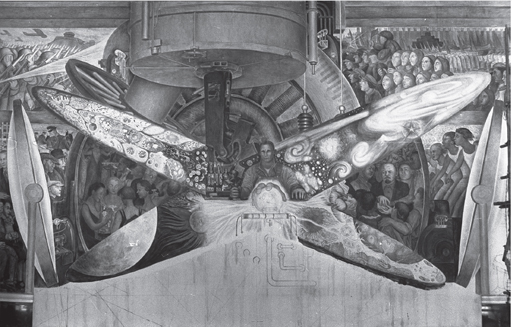

This balancing act between producing a mural that could satisfy a corporate patron as well as communicate a radical iconography pointing to a utopian future was not an easy one to maintain. Emboldened by his success in Detroit, Rivera left to paint a commission for Rockefeller in New York. Unfortunately for him, his success in Detroit was not to be repeated. In February 1934, Rivera’s mural Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future (Figure 13), which was over two-thirds complete on the ground floor of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) building in the Rockefeller Center, was hammered off the wall.

Rivera had diverted attention away from the actual conditions of capitalist crisis when he painted his Detroit Industry and instead painted an image of harmony on the shop floor that pointed towards a transcendence of the class contradictions of modern industrial production. In his RCA mural, he went one stage further. Here, he attempted to show how those contradictions could actually be overcome by depicting the opposing forces of capitalism and communism, with a portrait of Lenin just right of centre denoting the future triumph of the latter. All this in the Great Hall of the most important building in the Rockefeller Center, an ambitious building project that cost hundreds of millions of dollars at the height of the Great Depression.

It was this detail of the Russian revolutionary leader that brought work on the mural to a standstill and, after Rivera refused to remove it, ultimately ensured its destruction. According to Laurance Hurlburt, who produced the first major work on ‘los tres grandes’ in the United States, Rockefeller’s cultural philanthropy masked a hidden agenda in that his ‘primary objective lay in seeing that Standard Oil succeeded in avoiding what happened in other Latin American countries – the nationalisation of foreign-owned oil properties’ (Hurlburt, 1989, p. 9; Indych-López, 2009, p. 98). Hence Rivera’s one-man retrospective at the Rockefeller-dominated MoMA in 1931–32 and a further exhibition there in 1940 devoted to twenty centuries of Mexican art. Yet, with the removal of the mural, this strategy backfired and both Rockefeller and Rivera suffered accordingly. Rockefeller’s reputation as a friend of the Mexican people was seriously dented by what many considered an act of cultural vandalism against the continent’s pre-eminent artist. And, as already mentioned, the Cárdenas regime nationalised the Mexican oil industry in 1938 anyway. Rivera got the opportunity to repaint the mural later that year on the third floor of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City, but the controversy generated by the incident persuaded other rich patrons in the United States to withdraw from future sponsorship.