3.2 Empiricism

The Enlightenment is also known as the Age of Reason, but it was a very specific conception of reason that held sway. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe had seen a boom in knowledge brought about by the birth of modern science. This boom was accompanied by both optimism and a wish to identify what it was that investigators were suddenly getting right. What was it about science that made it so reasonable, and hence so successful?

See Plate 2 (Lecture on the Orrery in which a Candle is used to create an Eclipse by Joseph Wright of Derby), which relates to the comment below.

This painting shows a scientist (who perhaps intentionally resembles the physicist Isaac Newton, 1642–1727) giving a lecture using an orrery, a model of the solar system. Reverence for science is manifest in several ways. First, the demonstration, surrounded by the darkness of ignorance and prejudice, is giving off the light of knowledge. This distribution of light expresses what was seen as positive about science: its capacity to fight against ignorance and prejudice. (The metaphor of light was eventually adopted in the labels for the Age of Reason in all the main European languages, e.g. le siecle des lumieres in French, Aufklarung in German, illuminismo in Italian, and Enlightenment in English.) Second, the heads of the characters are themselves like planets rotating around the sun. This is perhaps intended to suggest optimism about the progress being made in the early scientific study of humanity itself. And third, the variety in age and sex of the people in the picture suggests that science could infiltrate and benefit the whole of society.

In many of Wright's paintings, including his An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), admiration of science was tempered by a fear of the power of this new knowledge, and uncertainty about the unquenchable thirst it could give rise to. In this instance, however, his representation seems to be wholly favourable.

Click to view Plate 2: Joseph Wright of Derby, Lecture on the Orrery in which a Candle is used to create an Eclipse, 1766, oil on canvas, 147.3 x 203 cm, Derby Museum and Art Gallery. Photo: reproduced by courtesy of Derby Museum and Art Gallery/Bridgeman Art Library/John Webb [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Many hoped to be able to classify all opinion as either reasonable or unreasonable according to how it compared with scientific opinion. An opinion would be classified as reasonable if arrived at in the same fashion as scientific opinions; it would be classified as unreasonable if arrived at in some other, less reputable fashion (e.g. superstition, reliance on tradition, idle speculation, etc.). But before this splitting of opinions into the reasonable and the unreasonable could be achieved, an explanation was needed of scientific success. The hunt was on for the magic ingredient that constituted the essence of the scientific attitude.

The most popular account of what set this new scientific age apart from the pre-Enlightenment era was and is empiricism (a nineteenth-century term). The backbone of empiricism is a simple claim:

Empiricism (roughly characterised): opinions are reasonable if, and only if, they are supported by evidence that is ultimately grounded in experience.

‘Experience’, here, can mean everyday observation using one or more of the five senses, but it is also meant to include rigorous scientific experimentation. Respect for this principle is what supposedly sets the scientific age apart from the pre-scientific age. In that earlier age, unsupported speculation was purportedly rampant; since the scientific revolution, experience served to constrain such speculation.

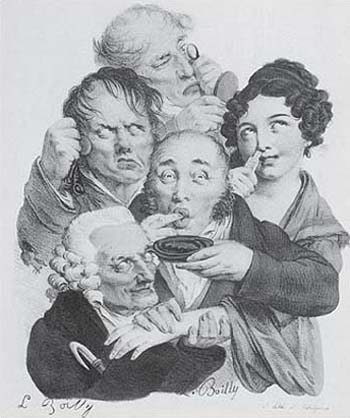

Empiricists claimed that experience was the source of all genuine knowledge; claims that didn‘t ultimately spring from the senses were to be dismissed as fanciful. This caricatured personification (Figure 2) of the senses reveals how not everyone was so convinced of the effectiveness of scientific methods at yielding all the truth and only the truth.

Expressed more negatively, empiricists are claiming that we should refuse to accept as true anything that has not been observed to be true. By this criterion, many religious doctrines are no more than unsupported speculation. Empiricists often denounced them as such in the period under discussion.

Empiricism as expressed in the simplified statement above has some embarrassing consequences. Moral and mathematical platitudes (e.g. that torturing people for fun is morally objectionable, or that 55 plus 55 necessarily equals 110) do not seem to require observational support, yet few would be prepared to denounce these judgements as unreasonable. The evidence for these and other reasonable opinions must come from some other source than the senses.

Empiricists tried to get around this difficulty in a variety of ways. They were anxious not to create any excuses for a return to the unscientific guesswork of previous eras, but were forced to acknowledge a limited role for reasoning that was not simply a response to experience. Though it would be interesting to look at the details of their efforts, this would take us too far afield. For our purposes it will be enough to sum up the empiricist agenda as follows: all opinions should be rejected unless backed up with evidence that is grounded either in experience or in one of some small number of permitted principles of abstract reasoning (e.g. mathematical principles).

Hume was empiricism's most eloquent advocate, as these uncompromising closing words of his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) show:

When we run over libraries, persuaded of these [empiricist] principles, what havoc must we make? If we take in our hand any volume, of divinity or school metaphysics for instance, let us ask: Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames, for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.

(Hume, 1975, p. 165)

The reference to flames, here, is almost certainly just a dramatic device. Enlightenment thinkers were or ought to have been hostile to censorship of opinion. For one thing, they held that reason and not force should be what determines public opinion. For another, most of them had themselves suffered censorship or repercussions for having published unpopular ideas. In actual fact, Hume did on at least one occasion seek to suppress material he found objectionable: in 1764 he tried and failed to prevent the publication of a mocking review of a friend's book by Voltaire (Mossner, 1980, p. 412). But whether he really wanted to burn library books for failing to pass his test is not relevant to our concerns. What is relevant is just that, in Hume's view, such books are entirely without value.

The empiricists' uncompromising attitude had risks as well as benefits. The benefits were evident in the explosive growth in scientific knowledge of the world about us and increasingly of ourselves. The main risk was that, by setting such high standards on what can permissibly count as a reasonable belief, empiricists would end up having to abandon many dearly held beliefs. Opinions on topics that weren't susceptible to empirical (i.e. scientific, experience-based) investigation would need to be dropped, leaving us floundering in ignorance on many important matters.

Hume claimed that such scepticism is really just realism about our predicament. On a wide number of topics – whether the sun will rise tomorrow, whether we have souls, whether these souls survive the death of our bodies, whether the external world exists – he insisted that, though we are unable to stop ourselves holding opinions, these opinions are not ones to which we are properly entitled. Hume's philosophy was a high water mark for classical empiricism. Rightly or wrongly, most of those who came after him were not prepared to embrace his resulting scepticism. They began instead to search for and defend alternative sources of evidence – alternative to the evidence of the senses, that is. By the late eighteenth century, the empiricists’ rigidity on this matter was beginning to unravel.