5.3 Do we have a duty to God not to commit suicide?

Why, you may be wondering, would anyone think that we have a duty to God not to take our own lives? Because it would have been so familiar to his original readership, Hume barely bothers to state the position he is opposing before criticising it. His concern is to refute the charge that in taking our own lives we would be ‘encroaching on the office of divine providence, and disturbing the order of the universe’ (paragraph 8). This position can be expressed less elegantly but more transparently as follows:

The sanctity-of-life argument against suicide: life ought not to be taken by anyone save God; so one ought not to take one's own life.

In a later idiom, the charge against suicide is that it involves playing God, i.e. making and acting on a decision that properly belongs to God and God alone. The phrase ‘playing God’ is often used even in a non-religious context to describe any action that involves the agent going beyond their proper station in the universe. In the Second World War some military strategists declared themselves uncomfortable at being called on to make decisions that would determine which of two cities would be heavily bombed. Their discomfort did not necessarily have a religious basis, and their use of the phrase ‘playing God’ in that context would often have been metaphorical. But the origins of the idiom lie in a genuine worry about literally taking God's decisions for him.

Without seeking to undermine the arguments for God's existence, Hume sets out to show that taking one's own life is unobjectionable. The thought that we have a duty not to take God's decisions for him, and in particular not to take the decision to end our own life, is, Hume suggests, preposterous even from the most reasonable theological perspective.

In order to show that from the most reasonable theological perspective available we should not condemn suicide, Hume must first establish what the most reasonable theological perspective available actually is. This task occupies him in paragraphs 6–7. At the very least, he suggests, the most reasonable theological perspective will assume the legitimacy of the argument from design (see the glossary if you need a reminder); this is the only argument for the existence of God that he believes is even remotely plausible.

Central to the argument from design is the assumption that order and harmony are evidence of a benign and powerful creator. Anyone who accepts the argument – in other words, anyone with a reasonable theological perspective – is committed to seeing order and harmony as God's handiwork. Any denial of the inference from order and harmony to divine influence would undermine the only plausible reason for accepting that God exists at all.

If the first component of any reasonable theological perspective is a commitment to the argument from design, the second is a recognition that order and harmony permeate every aspect of the universe. Each is observable within nature, within us, and within our relation to our environment. Since harmony and order are to be regarded as evidence of God's handiwork, this must mean that no part of the universe is free from God's influence.

The all-pervasiveness of harmony and order throughout the universe is something we can easily observe, says Hume (paragraph 6):

[A]ll bodies, from the greatest planet to the smallest particle of matter, are maintained in their proper sphere and function.

Hume is insistent on this point about the all-pervasiveness of harmony and order, and hence of God's influence (paragraph 6):

These two distinct principles of the material and animal world, continually encroach upon each other, and mutually retard or forward each other's operation.

In other words, all entities, including both inanimate and animate, appear subject to a single system of interlocking laws.

The significance of this is reached in paragraph 7:

When the passions play, when the judgement dictates, when the limbs obey, this is all the operation of God …

Consider the last of these three phenomena, the ‘obedience’ of our limbs to our decisions to move them. What he seems to have in mind here is that when you act – to scratch your ankle, for example – you are usually able to do so because the physical world accommodates your mental decision. In a non-harmonious world, your decision to scratch could just as easily be followed by your hand flying up towards the ceiling as its moving down towards your ankle. The fact that your hand moves down towards your ankle is a sign that human decision making is just as permeated by harmony as any other event in the universe, and so equally subject to God's benign influence as the rest of the universe.

A useful term to know here is ‘providence’. Divine providence includes all goings-on in the universe that are the direct result of God's influence. Many theologians have held that human action falls outside of divine providence, that our individual choices are not part of God's plan at all, and that we alone bear responsibility for them. Hume is arguing to the contrary that the entire universe, including each of our actions, falls within God's providential reach. His ground for thinking this, to repeat, is that harmony and order are manifest in human action just as they are manifest in the non-human sphere, and harmony and order are the surest sign there is of God's presence.

In paragraph 7 Hume addresses the thought that some of our actions do not really seem to be anyone's but our own. We cannot see God's hand at work in our actions looked at in isolation, he acknowledges. But seen as part of a harmonious system, our actions are as much permeated by God's influence as is the rest of the universe.

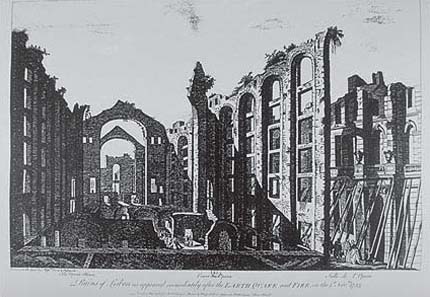

The Lisbon earthquake was mentioned earlier in a different connection. This event gave rise to debates that reflected issues salient at the time. Many focused on trying to understand the disaster as a natural phenomenon, and the science of seismology began in earnest around that time. Others were more concerned with reconciling such a cataclysmic event with their preferred conception of divinity. In particular, theologians struggled with the so-called problem of evil: if God is all-powerful and benevolent, why does he let terrible things happen? A popular answer to this problem prior to the Lisbon earthquake was that evil is brought into the world by human weakness. This was one reason why many, unlike Hume, thought that human action fell beyond God's providence. But while political corruption, murder and war could be understood in this way, earthquakes were clearly a different matter. A few tried to account for the earthquake as God's punishment for the sinfulness of Lisbon, which was perceived as a decadent city. But this was hard to reconcile with the fact that the ‘decadent’ opera house (Figure 4.6(a)) was joined in ruin by the cathedral and other religious buildings. In fact, five of Le Bas's six etchings contain one or more religious buildings. Figure 4.6(b) shows the patriarchal palace, which was the only major religious building to survive the tremor and the tidal wave. It served as an impromptu prayer centre before it too was lost in the fires that followed.

Exercise 14

Read paragraphs 6–7. Their meaning is occasionally quite elusive. A useful maxim to adopt when this happens is to aim to get the author's basic gist, then move on, coming back later if you have to. With this in mind, what is the basic gist of these two paragraphs?

Discussion

Hume is attempting to set out what the most reasonable theological perspective is; he has yet to say anything about suicide from this perspective. The first component of this perspective is a commitment to the argument from design. This is left largely implicit by Hume, save where he announces that ‘sympathy, harmony, and proportion, … [afford] the surest argument [for] supreme wisdom’ (paragraph 6). The second component is recognition that harmony and order permeate every aspect of the universe, including the human sphere. Putting these two components together, even events taking place in the human sphere -our own actions – must be regarded as part of God's plan (i.e. as ‘belonging to divine providence’). Or, if you like, our actions are also God's actions. This is true of all actions, so there are no grounds for distinguishing between actions that are our own and those that belong to God.

Having established that, on pain of having to reject design as a sign of God's existence, all our actions need to be treated equally as a part of God's plan, Hume unveils the relevance of this for the morality of suicide (paragraph 8).

It is absurd, he claims, to condemn an act of suicide as ‘encroaching on the office of divine providence’, that is, as doing what God and only God may do. Such condemnation would be absurd because every action would then have to be condemned for the same reason. If we condemn acts of suicide for encroaching on God, we would also need to condemn acts of ankle scratching. Both actions fall inside the scope of divine providence. Both have equal status as part of God's grand design.

Hume is criticising any attempt to establish a division between ordinary decisions and sacred decisions. Decisions of the first kind would belong to us alone; decisions of the second kind would belong to God alone. His long discussion of divine providence is meant to have shown that such a division is misguided. ‘Shall we assert’, asks Hume in paragraph 8,

that the Almighty has reserved to himself in … [some] peculiar manner the disposal of the lives of men, and has not submitted that event [i.e. the disposal of human life], in common with others, to the general laws by which the universe is governed? This is plainly false.

It is ‘plainly false’ because having a specially reserved sphere of influence is incompatible with the universality of divine providence. All types of action, from ankle scratching to suicide, are on the same footing; indeed, they are on the same footing as every event in the universe. All are subject to the universal laws of nature. These regular, ordered and harmonious laws of nature are our only assurance that God exists at all, so must be taken as a sign of God's influence.

Exercise 15

Read paragraph 8. How does Hume's view of providence bear on his views on the moral acceptability of suicide?

Discussion

Hume holds that no distinction can be drawn between those decisions that belong to God and those that do not: God's providence is total. So ending life cannot be treated as unique in belonging exclusively to God.

By the end of paragraph 8 Hume has stated the main argument of his essay. The principal value of the essay lies in this discussion of the all-pervading presence of divine providence, and its relevance for the morality of suicide. The remainder is repetition or else it introduces some short and relatively easy-to-grasp theological considerations. So now would be a good time to state Hume's reply to the sanctity-of-life argument in as simple a way as possible:

Hume's reply to the sanctity-of-life argument: any reasonable theology will see order and harmony as a sign of God's influence; order and harmony are present equally in all human actions; so there is no distinction to be made between actions (e.g. suicide) that belong to God and actions (e.g. ankle scratching) that do not.

Exercise 16

Read paragraphs 9–14. Paragraphs 11–14 recapitulate the core ‘providence’ argument discussed already, so treat this as an opportunity to cement your understanding of his position. Before that, jot down a sentence capturing the objection Hume is responding to in paragraph 9. Then do the same for paragraph 10.

Discussion

Paragraph 9: the huge significance of the decision whether to end a human life should lead us to regard it, unlike other decisions, as one that only God may take. Paragraph 10: to take one's life is to insult God by destroying his creation. (You may have come up with a different emphasis.)

You may have recognised in Hume's reply to the objection in paragraph 9 the comments that so annoyed the anonymous commentator for Monthly Review quoted earlier. Actually, Hume presents several different replies in quick succession. In the first of these he suggests that ‘the life of a man is of no greater importance to the universe than that of an oyster’. It is not clear what Hume means by ‘importance to the universe’, but on the face of it this is a bizarre claim. He makes a similar-sounding claim in comparing diverting the Nile with diverting the flow of blood through human veins. This is a case where, as interpreters, we have to make a decision. Either Hume had a good but obscure point to make with these examples, and we should pause to work out what that point is. Alternatively he was just being sloppy, in which case we should ignore his remark and move on to his other responses. I am going to adopt the latter strategy.

A more promising reply (I suggest) is embedded elsewhere within paragraph 9. Hume points out that we don't condemn those who save their own lives by ‘turn[ing] aside a stone which is falling upon … [their] head’ for stepping on God's toes. Yet deciding to save a life is just as significant as deciding to end one. Why then should we make this complaint when it is a matter of ending our lives? The same reasoning used to condemn those who take their own lives could be used to condemn those who save their own lives. Both the taker and the saver could be said to be acting ‘presumptuously’ in taking such huge decisions. Hume treats this as showing the reasoning to be equally absurd in each case.

In paragraph 10 Hume is responding to the thought that by killing oneself one is destroying God's greatest creation. This would be insulting to God, rather as destroying a watch would be insulting to the watch's maker. Hume, however, is concerned with acts of suicide that are motivated by inconsolable misery and incurable illness. So a better analogy would be with the act of destroying a watch that is already permanently broken down and useless. Throwing out such a watch is in fact an act of respect for the watchmaker.

Exercise 17

Remind yourself of the structure of the essay as stated in paragraph 5. Then read the remaining paragraphs of the essay. Paragraphs 15–16 deal with duties to society; paragraphs 17–18 deal with duties to self.