While the news of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 brought joy and celebration in Britain and its allied countries, in Germany, the reaction was different. Many thought that victory could have been achieved if only Germany had held out a little longer – and that lack of staying power was attributed to civilians. Soon, the myth spread that Germany had not really been defeated at the front. Orderly columns of German soldiers marching home after the Armistice only served to confirm this impression – after all, the war had not been fought on German soil, no news of major defeats had ever reached the German population, and victory had been promised by the Government on many occasions.

While the news of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 brought joy and celebration in Britain and its allied countries, in Germany, the reaction was different. Many thought that victory could have been achieved if only Germany had held out a little longer – and that lack of staying power was attributed to civilians. Soon, the myth spread that Germany had not really been defeated at the front. Orderly columns of German soldiers marching home after the Armistice only served to confirm this impression – after all, the war had not been fought on German soil, no news of major defeats had ever reached the German population, and victory had been promised by the Government on many occasions.

Deeply frustrated soldiers returned to defeated Germany after the Armistice, unwilling to make their peace with post-war society. Youths who had come of age during the war knew nothing but fighting. Many soldiers had experienced a brutalisation which made it difficult for them to return to civilian life. Instead of the expected imminent victory they returned to hunger, deprivation and the humiliation of a lost war, and to an unrecognisable post-war world.

It seemed as if only a victory could justify the incredible losses Germany had suffered. Over two million soldiers had died and more than 700,000 civilians had perished as a result of hunger and malnutrition. Including victims of the Spanish flu epidemic, about three million dead were mourned. Now the country was being humiliated by vindictive victors, leading to resentment of those who had signed the Armistice agreement and the subsequent peace agreement at Versailles. Most prominently among them was the Catholic Centre Party politician Matthias Erzberger. His role in the Armistice negotiations and during the peace negotiations that followed made him the most hated man in the Weimar Republic. Ultimately it led to his violent death in 1921 at the hands of some of the disaffected former soldiers who were unable to make their peace with the new German Republic and who blamed Erzberger above all for Germany’s demise.

Who was Matthias Erzberger?

From very humble beginnings Matthias Erzberger went on to become one of the Weimar Republic’s most influential politicians. Born in 1875, he was a self-made man, hard-working, ambitious, and with encyclopaedic knowledge, who became the youngest member of Reichstag at 28 for the Catholic Centre Party (Zentrumspartei). In November 1918, he ended up in a train carriage in Compiègne, signing the Armistice Agreement on behalf of the German Government. When he was told he should fulfil this role, he did not shy away from this momentous act even though he knew that he would almost certainly pay a personal price for it.

This was the first time that a politician, rather than a military leader, concluded an armistice agreement. Initially, Erzberger was asked to be a member of a group of Germans who would travel to France to conclude the Armistice, headed by an officer, General Erich von Gründell. However, when the group arrived at the German military headquarters in Spa in Belgium, Erzberger was told that Gründell was unsuitable for the role, and instead Erzberger, the only civilian in the party, was appointed Chairman of the Ceasefire Commission. Erzberger was accompanied by General von Winterfeldt, along with Graf von Oberndorff and Captain Vanselow as a representative for the Navy.

The journey to Compiègne was adventurous and traumatic. Erzberger and his military colleagues were nearly killed in a car crash along the way. He witnessed, for the first time, the extent of the destruction wreaked upon French towns and villages. In his memoirs, he describes the destruction he witnessed, commenting that the ruins in the town of Chauny were ‘like ghosts’ in the moonlight and there being ‘no living soul’ left.1 The party were forced along a circuitous route to impress upon them the extent of the destruction and they arrived at Compiègne on 8 November, exhausted and sleep-deprived after an arduous journey. Erzberger described the journey as even more traumatic than a journey three weeks previously to his only son’s deathbed. In Compiègne, they faced the French General Foch, the Allies’ supreme military commander.

Foch was in no mood to negotiate. He would dictate his terms, and the German delegation was to accept them. According to Winterfeldt, Erzberger fought like a lion to change Foch’s mind, but to no avail. At the end of the negotiations, there was no handshake. Erzberger portrayed Foch in his memoirs as cold and forbidding, barely human.

Negotiating the armistice. Behind the table, from the right: the French General Maxime Weygand and Marshal Ferdinand Foch (standing), the British naval officers Rosslyn Wemyss,George Hope and Jack Marriott. Standing in front of them are the German State Secretary Matthias Erzberger, Major General Detlof von Winterfeldt, Alfred von Oberndorff of the Foreign Office and Captain Ernst Vanselow of the German Navy.

Negotiating the armistice. Behind the table, from the right: the French General Maxime Weygand and Marshal Ferdinand Foch (standing), the British naval officers Rosslyn Wemyss,George Hope and Jack Marriott. Standing in front of them are the German State Secretary Matthias Erzberger, Major General Detlof von Winterfeldt, Alfred von Oberndorff of the Foreign Office and Captain Ernst Vanselow of the German Navy.

The armistice document was signed around 5 am on 11 November and was to become effective at 11 am. At 11 o’clock, the guns on the Western Front fell silent.

After the signing Erzberger learnt that the Kaiser had fled to Holland and that a Republic had been declared in Berlin. When he returned to Spa to meet Germany’s highest military leaders, he was congratulated by General Hindenburg and his second in command, Wilhelm Groener.2 Groener’s ‘keenest expectations’ had been surpassed, while Hindenburg thanked him for his ‘extremely valuable service’ for the Fatherland. They would soon turn against Erzberger whom they had sent to France so that he could be a civilian scapegoat for the military impasse they had created.

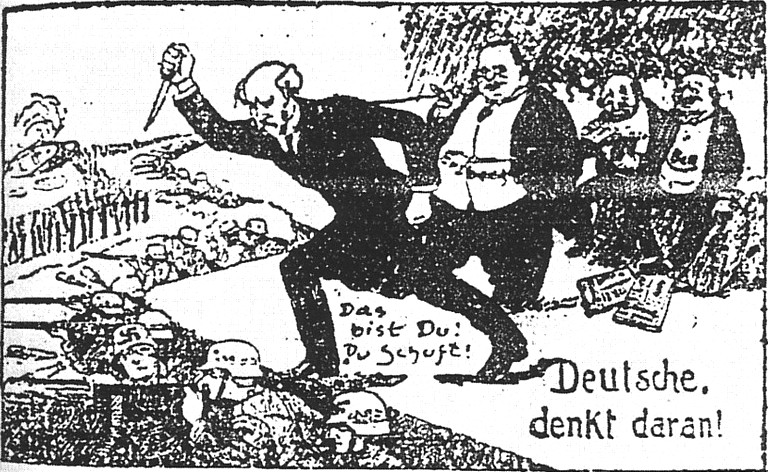

Erzberger described his journey to Compiegne as a ‘way of the cross’, and the hardest and most bitter task of his working life. But he felt he had done what he could for his country, and pointed to the many small adjustments he had been able to make to the terms, negotiating hard, for example, over the numbers of lorries to be handed to the Allies or the scale of areas to be demilitarised. Most of all, he felt he had averted Germany’s complete defeat and possible carving up by the victors. But his card was marked, as enemies of the new Republic equated his name with that of the inglorious end of the war, with the occupation of German territories west of the Rhine, and with the handing over of the German Navy to the enemy. Soon the military leaders who had despatched Erzberger to act in their name disassociated themselves from the Armistice agreements, allowing the myth of a country betrayed by parliamentarians to take hold. Erzberger became the focal point of much of the anger of the disaffected. Previously resented for his Catholicism, he was now painted as a Jewish traitor who had stabbed Germany in the back.

A caricature from 1924 shows Philipp Scheidemann and Matthias Erzberger, as they stab the German front soldiers from behind.

A caricature from 1924 shows Philipp Scheidemann and Matthias Erzberger, as they stab the German front soldiers from behind.

Erzberger’s role in the new Republic

After the elections in January 1919, Erzberger entered the government of the German Republic led by Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann, as Minister without a specified portfolio, but responsible for matters relating to the Armistice. After Scheidemann’s resignation over the terms of Treaty of Versailles, Erzberger advanced to Finance Minister and Vice Chancellor under Chancellor Gustav Bauer. In this role, he advocated the acceptance of the Versailles peace conditions which he considered unbearable and unrealistic, but not unacceptable, because he feared that otherwise Germany would be divided up by the victors. He realised that there was no military or political alternative to accepting the treaty. But he hoped that by appearing cooperative, further concessions could be negotiated later.

He was already despised by conservatives and the right in Germany because he had signed the Armistice. Now his support for Versailles branded him a ‘fulfilment politician’ and made him the victim of further hate campaigns. He was considered a ‘November Criminal’, having betrayed Germany at the end of the war. And there were other reasons to hate Erzberger. In his new role as the Weimar Republic’s Finance Minister he introduced a new tax system which taxed the rich and those who had profited from the war, and he also introduced an inheritance tax, all of which offended the bourgeois old elites. Conservative and right-wing politicians begun a vendetta against him.

The assassination

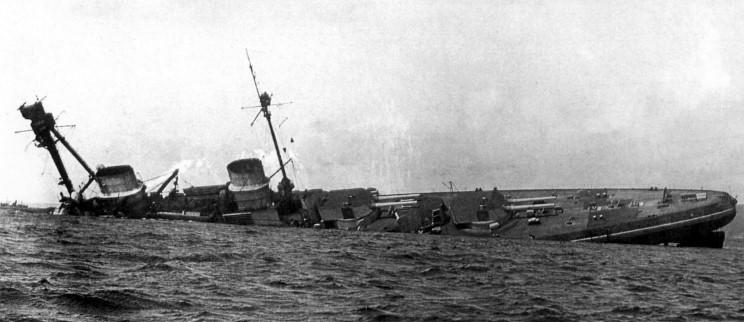

Erzberger was well aware that his life was in danger, and he survived several assassination attempts. In post-war Germany, violence in the streets was an almost daily occurrence. By 1922, there had been some 350 political murders, many committed by Freicorps organisations (consisting of disaffected former soldiers). Among the victims of Freicorps violence were the Socialists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Erzberger was high on the list of potential victims as many would-be assassins hated him for his involvement in the signing of the Armistice and for his support of Versailles. He was also blamed for the fact that the German Navy had been handed over to the Allies and interred at Scapa Flow where it had been scuttled in the summer of 1919.

Erzberger was murdered by two young assassins, Heinrich Tillessen and Heinrich Schulz, who had direct links to the Navy and to the so-called ‘Organisation Consul’ which had been founded by disillusioned naval officer Korvettenkapitän Erhardt.

Tillessen had been forced to deliver a torpedo boat to Scapa Flow and was responsible for its scuttling in June 1919, a traumatic experience for him, as for all the other captains who sank their own ships, rather than hand them over to the Allies. He ended up a prisoner of war in Britain until 1920. In the summer of 1921, he was recruited by ‘Operation Consul’ to assassinate Erzberger. He considered the politician personally responsible for the fate of the Navy and ‘his’ ship.

SMS Derfflinger sinks at Scapa Flow after being scuttled by her crew.

SMS Derfflinger sinks at Scapa Flow after being scuttled by her crew.

While on holiday in the Black Forest and walking with a friend, Erzberger was shot dead by the two young men. Many in the Weimar Republic were appalled at this act of violence, but Erzberger’s enemies rejoiced at his demise, including the former Kaiser Wilhelm II, who celebrated the news with champagne in his exile in Doorn in the Netherlands. The assassins meanwhile, were assisted in fleeing the country, first to Austria, then Hungary, Spain, Africa, returning to Cologne in 1932 .

The aftermath of the murder

In 1933, President Hindenburg signed an amnesty law which cleared anyone who had committed a political murder in the Weimar Republic – including Erzberger’s murderers who no longer had to answer for their crime. However, after the Second World War, the two assassins were arrested by the US occupying forces in Heidelberg in 1945, tried in 1946 - and acquitted on the basis of the 1933 law. This decision was met with outrage, and eventually a retrial in 1947 found the two men guilty. Tillessen was sentenced to 15 years in prison, Schulz for 12, but both men were out of prison on license by 1952.

Today, Erzberger’s reputation as one of the Weimar Republic’s most able advocates has been restored as the Bundestag decided to name a new government building in Berlin after him. Today he is celebrated as an ‘outstanding parliamentarian’ 3. In accepting the Allied armistice in November 1918, he had prevented a worse fate for Germany, whose completely military defeat and division he thus helped to avert. Throughout his political career he fought for German democracy in the knowledge that doing so put his life in danger. His role in the events of November 1918 has been all but forgotten – and yet, he was instrumental in arranging the Armistice, convinced that it was the only way to stop the war and prevent further suffering in Germany. He paid for this conviction with his life.

__________________

1 Matthias Erzberger, Erlebnisse im Weltkrieg, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart, Berlin 1920, p.329.

2 Ibid, p.339.

3 https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2017/kw12-de-wels-erzberger/499218

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews