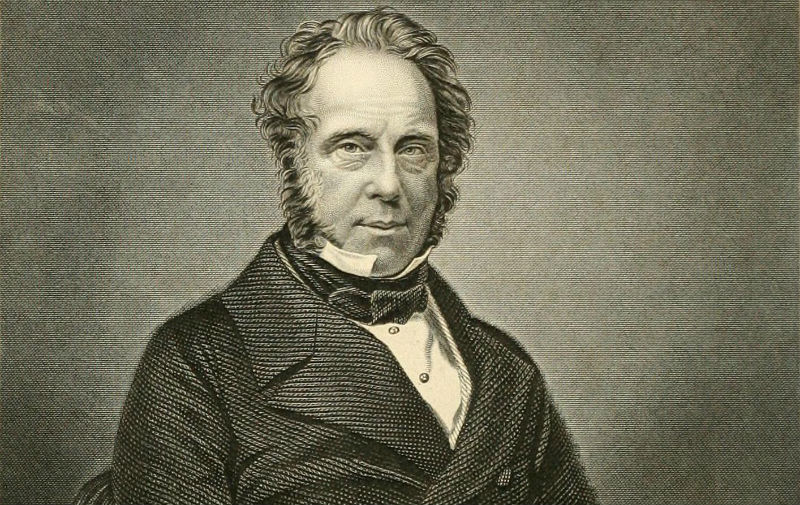

Lord Palmerston

Lord Palmerston

Background: In 1847, Don Pacifico, a former Portuguese consul-general to Greece, had his home in Athens vandalised by an anti-semitic mob. Pacifico had been blamed for a ban on the burning of an effigy of Judas; it was claimed that the son of Greece's Minister of War and undercover police had been part of the mob. Because Pacifico was a British citizen, the UK government became involved, and Lord Palmerston advised him to present an itemised list of damages, seeking recompense. The Greeks refused, suggesting that the demands were far larger than any damages that might have been incurred. By 1849, King Otto had not only refused to pay up, but had also suspended repayments of a loan from London. Things escalated, and British ships were sent to blockade Greek ports until payments were made - the origins of "gunboat diplomacy". Adding an extra layer of complication, Greece had only been created in 1832 as part of the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire - and under the terms of her creation, was meant to be protected by Russia, France, and Britain.

In June 1850, the Lords rose to condemn Palmerston's approach to the crisis...

A reference to our report of Monday night's proceedings in the House of Lords will show the disingenuous spirit in which the whole of that extraordinary discussion was conducted.

The obvious intention of the Noble Lord, who on that day brought forward in an elaborate harangue his motion of censure upon the British Government in regard to the Greek question, was to elicit from the assembled Peers of England a division condemnatory of the foreign policy of Viscount Palmerston.

Such, we repeat, was the purpose held in view by Lord Stanley, and fully must Lord Stanley have been satisfied by that majority of thirty-seven which decided in favour of his proposition.

Let it not be considered, however, for a single instant that the Cabinet have through this disgraceful division experienced the slightest discomfiture.

On the contrary, the circumstance that out of three hundred and one of our hereditary legislators, either "present" or "proxies" - 169 were in favour of, and 132 opposed to, the Noble Lord's most invidious resolution - so far from militating in any manner against Lord Palmerston individually, or against his Ministerial colleagues collectively, tends directly and decisively to elevate them yet higher in the scale of public estimation.

For - the majority was a majority in the Upper House of Parliament. It was a majority in that assembly whose sympathies are, with scarcely one exception, on the side of the most arbitrary and despotic governments of Christendom.

The House of Lords knew well enough by that by voting as they did on Monday they would further the wishes of the Russian cabinet and subserve their own consciences to the gratification of the Russian Autocrat.

The House of Lords knew, moreover, equally well that by so acting they would most effectually irritate that vast body of the liberal-minded population of England who respect, above all things, the inalienable claims of justice, and who recognize in the illustrious statesman at the head of the Foreign Department the boldest, the ablest, the wisest, the most adroit, the most experienced of the vindicators of our national honour and of the conservators iof our national reputation.

Hence the House of Lords voted, in opposition to all truth, in opposition to all candour, in opposition to all fair-dealing and common sense, in favour of the motion brought forward by Lord Stanley, in condemnation of the Greek policy of her Majesty's Principal Foreign Secretary.

A distinguished orator, such as the Noble Leader of the Protectionist Opposition, could not of course deliver a speech of such extraordinary length as the one with which he opened Monday evening's discussion without displaying many of those capacities as a rhetorician which have long since gained him a name among the master of eloquence, and in the brilliant manifestation of which he knows so well how to dazzle the judgments of the Senate.

Yet we are bold to say that never before, in the annals of the Parliament, was pronounced any oration more shallow in logic, or more shamefully evasive of the real facts under examination. Almost all the mingled irony and vituperation levelled by Lord Stanley against Viscount Palmerston for his conduct towards the Greek Government was restricted to the ridicule of the various claims for which England has been demanding reparations.

A more impudent blinking of the real matter at issue between the cabinets of Athens, of Paris, and of London, could not, by any possibility, have been devised. Why, the question was - not whether the claims put forward by Great Britain were good, bad, or indifferent - but whether France had, or had not, been treated in a shuffling manner by our diplomatists acting on behalf of our Government.

As to the claims - their justice have been recognized over again, both by the French Republic and the Greek Monarchy. It was consequently worse than frivolous, on the part of Lord Stanley, to endeavour to demonstrate the unwarrantableness of demands which have been bowed as to as most rational by the several negotiators in the late correspondence.

Especially frivolous was it of Lord Stanley to deprecate the force of such a claim as the one advanced in reference to the seizure of the boat's crew of her Majesty's ship the Spitfire, by remarking that the authorities at Patras could not be supposed to recognize the boat's crew as seamen in the Royal Navy of England, seeing as they were without uniforms!

Then again, as to the inquiry why summary compensation for the insult had not been required by the officers of the Spitfire - it was as absurd as to ask why a bumboat could not extort reparation for a like insult from the garrison of Gibraltar.

If, however, Lord Stanley rendered himself ridiculous by his miserable begging of the actual question at issue - what can we possible say in allusion to the spiteful twaddle of the Earl of Aberdeen?

The former, with his every syllable envenomed by that canker of suppressed remorse which eats the heart and embitters the tongue of every political renegade; the latter prosing with the complacent egotism of unconscious mediocrity, with the imagination of a plagiarist, the originality of a dilectus, and a face worth of being immortalized among the highly "proper" and ceremonious founders of Agapemone.

Such enormous misapprehension of all the responsibilities of foreign statesmanship, such sand-blind ignorance of the veriest rudiments of the science of diplomacy, such elaborate dullness and redundant folly, were perhaps never before heaped together within the compass of a single discussion.

Beyond which, throughout the whole of these attacks upon the Greek policy of Lord Palmerston, and consequently by implication of Her Majesty's Government, the real matter of debate was entirely overlooked.

- originally published in the Hampshire/Portsmouth Telegraph, 22, June 1850

What happened next? The Commons also debated the approach taken by the Government; here, Palmerston was endorsed as having protected the "dignity" of the nation in a vote which split 310-264 in his favour. On July 18th, an agreement between the Greek and British governments was struck - a Commission would assess the true depth of the damages incurred by Pacifico, and payments would be made. The gunboats were called off; Pacifico was awarded £500 and 120,000 drachma to compensate him. With this, he relocated to London to live out his years.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews