3.3 Heritage and tourism

John Urry’s (1990) criticisms of Hewison’s The Heritage Industry took another form, providing a useful corrective to the way in which both Wright and Hewison had criticised heritage as ‘false’ history. Focusing particularly on museums, he suggested that tourists are socially differentiated, so an argument that they are lulled into blind consumption by the ‘heritage industry’, as had been suggested by Hewison, could not hold true. Urry drew an analogy with French philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of ‘the gaze’ to develop the idea of a ‘tourist gaze’. The tourist gaze is a way of perceiving or relating to places which cuts them off from the ‘real world’ and emphasises the exotic aspects of the tourist experience. It is directed by collections of symbols and signs to fall on places that have been previously imagined as pleasurable by the media surrounding the tourist industry. Photographs, films, books and magazines allow the images of tourism and leisure to be constantly produced and reproduced. The history of the development of the tourist gaze shows that it is not ‘natural’ or to be taken for granted, but developed under specific historical circumstances, in particular the exponential growth of personal travel in the second part of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, it owes its roots to earlier configurations of travel and tourism, such as the ‘Grand Tour’ (the standard itinerary of travel undertaken by upper-class Europeans in the period from the late seventeenth century until the mid-nineteenth century which was intended to educate and act as a right of passage for those who took it), and in Britain, the love affair with the British sea-side resort which had its hey-day in the mid-twentieth century.

Tourism and heritage must be seen to be directly related as part of the fundamentally economic aspect of heritage. At various levels, whether state, regional or local, tourism is required to pay for the promotion and maintenance of heritage, while heritage is required to bring in the tourism that buys services and promotes a state’s, region’s or locality’s ‘brand’. Heritage therefore needs tourism, just as it needs political support, and it is this that creates many of the contradictions that have led to the critiques of the heritage industry relating to issues of authenticity, historical accuracy and access.

The connection between heritage and travel might be seen to have a much deeper history. The fifth-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus made a list of the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’, the great monuments of the Mediterranean Rim, which was reproduced in ancient Hellenic guidebooks. Herodotus’ original list was rediscovered during the Middle Ages when similar lists of ‘wonders’ were being produced. What is different about the World Heritage List is that, as a phenomenon of the later part of the twentieth century reflecting the influence of globalisation, migration and transnationalism, it spread a particular, western ‘ideal’ of heritage. This image of heritage, and particularly World Heritage as a canon of heritage places, began to circulate freely and to become widely available for the consumption of people throughout the world. Another important difference is the acceleration in transforming places into heritage – what Hewison and Wright referred to as ‘museumification’ – which involves the almost fetishistic creation of dozens of different lists of types of heritage. Hewison connected this growth in heritage and its commodification with the experience of postmodernity and the constant rate of change in the later part of the twentieth century.

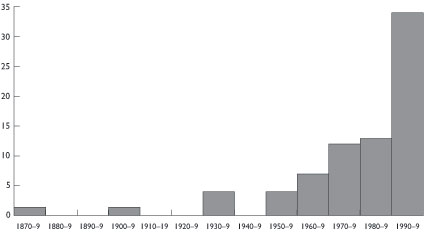

The growth in heritage as an industry can be documented at a broad level by graphing the number of cultural heritage policy documents developed by the major international organisations involved in the management of heritage in the western world. These organisations include the Council of Europe, the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the International Committee on Archaeological Heritage Management (ICAHM, a committee of ICOMOS), the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), the Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC), the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Monuments Fund (WMF). The graph of numbers of policy documents over the course of the twentieth century, as the organisations came into being, shows a major period of growth after the 1960s and 1970s (see Figure 3).

Urry was interested in explaining the power of the consumer to transform the social role of the museum. He suggested that the consumer has a major role in selecting what ‘works’ and what does not in heritage. It is not possible to set up a museum just anywhere – consumers are interested in authenticity and in other things that dictate their choices, and they are not blindly led by a top–down ‘creation’ of heritage by the state:

Hewison ignores the enormously important popular bases of the conservation movement. For example, like Patrick Wright he sees the National Trust as one gigantic system of outdoor relief for the old upper classes to maintain their stately homes. But this is to ignore the widespread support for such conservation. Indeed Samuel points out that the National Trust with nearly 1.5 million members is the largest mass organisation in Britain ... moreover, much of the early conservation movement was plebeian in character – for example railway preservation, industrial archaeology, steam traction rallies and the like in the 1960s, well before the more obvious indicators of economic decline materialised in Britain.

The outcome of Urry’s discussion of heritage was to shift the balance of the critique of heritage away from whether or not heritage was ‘good’ history to the realisation that heritage was to a large extent co-created by its consumers.

The popular appeal of heritage can be demonstrated by ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions of artefacts and archaeological finds, such as the Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, a worldwide travelling exhibition of artefacts recovered from the tomb of the eighteenth dynasty Egyptian pharaoh which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum in 1972, when it was visited by more than 1.6 million visitors. Over 8 million visited the exhibition in the USA. A follow-up touring exhibition called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs ran during the period 2005–8. Interestingly, instead of being shown in London at the British Museum, this exhibition was displayed in a commercial entertainment space, the O2 Dome in south-east London, which contains concert venues and cinemas (see Figures 4 and 5). Such an approach to the display of archaeological artefacts shows the way in which the formal presentation of heritage has moved outside the traditional arenas in which it would be presented, to be viewed almost exclusively as a ‘popular’ form of entertainment.

Ironically, it was to this same commercialisation of heritage and the past that archaeologist Kevin Walsh (1992) turned in support of the ideas put forward by Hewison in The Heritage Industry. Walsh argued in his book The Representation of the Past that the boom in heritage and museums has led to an increasing commercialisation of heritage which distances people from their own heritage. He suggested that the distancing from economic processes – a symptom of global mass markets that has been occurring since the Enlightenment – has contributed to a loss of ‘sense of place’, and that the heritage industry (and its role in producing forms of desire relating to nostalgia) feeds off this. Loss of a sense of place creates a need to develop and consume heritage products that bridge what people perceive to be an ever increasing gap between past and present. Walsh used an argument similar to one employed by David Lowenthal in The Past is a Foreign Country (1985) and later in The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (1997). Lowenthal suggested that paradoxically the more people attempt to know the past, the further they distance themselves from it as they replace the reality of the past with an idealised version that looks more like their own reality.