Background

John Webster (c.1580–c.1634) was Shakespeare’s contemporary, though sixteen years younger. He makes a brief appearance in the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love as a boy who tortures mice, spies on Shakespeare’s love-making, and feels inspired to take up the pen himself after seeing Shakespeare’s blood-soaked revenge tragedy, Titus Andronicus. ‘Plenty of blood. That’s the only writing’, he asserts. This affectionate but crude caricature testifies to Webster’s reputation for writing dark and violent plays. Yet it also testifies to the enduring popularity of those plays. Shakespeare had many gifted colleagues in the play-writing business, but only two – Webster and Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593) – are graced with roles in this enormously popular mainstream movie about the late sixteenth-century theatre scene. This course will look at Webster’s most well-known play, The Duchess of Malfi, and consider some possible reasons for the play’s continued prominence in the twenty-first-century theatre repertoire.

The Duchess of Malfi does indeed have ‘plenty of blood’, but this is nothing unusual in Renaissance tragedies. Webster’s play is a tragedy about a forbidden love, more specifically a forbidden marriage, which leads ultimately to the deaths of the lovers and many others. Webster’s focus in his tragedy of love is class, or rank, to use a more authentically early modern term. Historians of the period often prefer the term ‘rank’ on the grounds that it better captures relationships in a highly stratified society where the vertical ties of patronage and deference were strong and class consciousness poorly developed in social groups below the level of the ruling elite. Both terms will be used in this course. At the centre of The Duchess of Malfi stands a heroine rather than a hero, which is fairly unusual in Renaissance tragedy. The play also contains an extremely enigmatic and sinister villain. This course will examine how Webster represents his heroine’s marriage for love, which goes against the wishes of her aristocratic family with disastrous consequences.

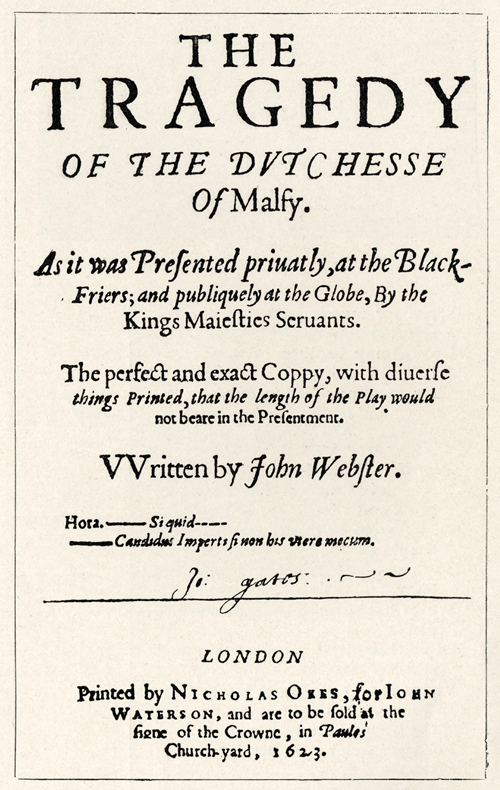

The Duchess of Malfi was first performed in 1613 or 1614 by the King’s Men, the acting company to which Shakespeare belonged. The play was not printed until around ten years later in 1623, in quarto, a smaller and less expensive edition than the larger folio size used for the first edition of Shakespeare’s complete works. The title page of this edition (shown in Figure 1) tells us that the play ‘was presented privatly, at the Blackfriers and publicly at the Globe’; that is, the play opened at the Blackfriars, the company’s indoor theatre, and then played at the open-air Globe. The title page also informs potential readers that the text of the play is the ‘perfect and exact Coppy, with diverse things Printed, that the length of the Play would not beare in the Presentment’; in other words, the play text includes numerous passages that were cut for performance. The publisher, then, appears to be trying to tempt buyers with the prospect of a longer, fuller version of the play than had ever been seen in the theatre. This is testament to Webster’s fame and reputation as a dramatic poet, as is the announcement of the author’s name in the next line, in larger type. The 1623 quarto is the only substantive text of the play that we have, and modern editions and productions are based on it. We have no way of knowing what The Duchess of Malfi looked like in its first performances, beyond assuming that it was shorter than the text that has descended to us. What is interesting is that the title page of the 1623 quarto draws such a clear distinction between the play in performance and the play as a text to be read and savoured in the study.