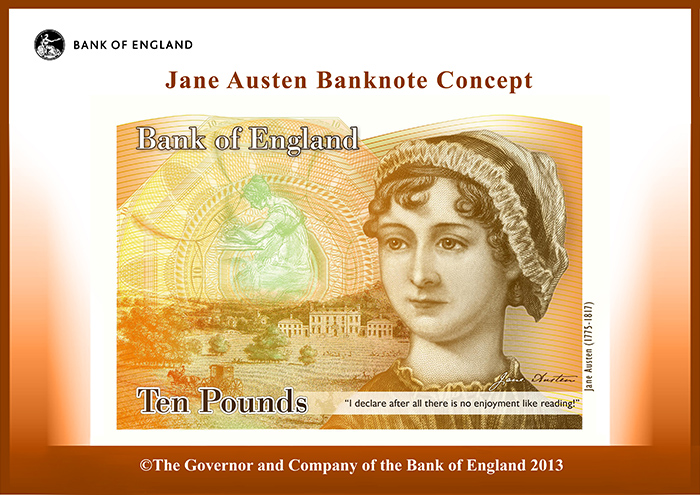

'Austenmania’ has been a prominent feature of British culture for the last decade and more, and never more so than in the year which marks the bicentenary of her death. The extent of 21st century national and international popular investment in Jane Austen and her novels, expressed in part by the decision to put her image on the new £10 note, would have surprised Austen’s contemporaries. They knew her as a novelist who had achieved a definite but commercially modest success with the four novels published in her lifetime: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815). Her early work, Northanger Abbey, and her last completed novel, Persuasion, would only be published posthumously in December 1817. Her low public profile at the time is underscored by the lack of any accredited portrait other than the sketch done of her by her sister Cassandra, which forms the basis of all subsequent likenesses, including that used on the banknote.

'Austenmania’ has been a prominent feature of British culture for the last decade and more, and never more so than in the year which marks the bicentenary of her death. The extent of 21st century national and international popular investment in Jane Austen and her novels, expressed in part by the decision to put her image on the new £10 note, would have surprised Austen’s contemporaries. They knew her as a novelist who had achieved a definite but commercially modest success with the four novels published in her lifetime: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815). Her early work, Northanger Abbey, and her last completed novel, Persuasion, would only be published posthumously in December 1817. Her low public profile at the time is underscored by the lack of any accredited portrait other than the sketch done of her by her sister Cassandra, which forms the basis of all subsequent likenesses, including that used on the banknote.

To think about the image of Jane Austen as it appears on the new banknote, however, allows us to think about what Austen means in contemporary culture. The choice itself suggests, for instance, that her image has become generally recognisable, or that if it isn’t, then it should be. It suggests, moreover, that Austen, whether you consider her as a person, an author, or a brand, can plausibly describe -- and be described as -- solid and enduring worth. It also suggests that she is a national treasure -- that the books she wrote in the front room of a red-brick Georgian house set in a village at the heart of the shires, in deepest, leafiest Hampshire, are so ‘English’ that they can be regarded as being as good as Bank of England gold.

The detail of the image is also illuminating. The portrait of Austen shows her as a young woman – not, at any rate, in her forties – and rather prettified by comparison even to Victorian prettifications.

Strangely, the quotation from Pride and Prejudice that runs beneath the portrait itself – ‘I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading’ – which is so placed as to appear to voice Austen’s own sentiments, casts her more as a reader than a writer. The quotation is all the odder as in context it is a very sharp dig at the yawning pretensions of Miss Bingley, at that moment interrupting everyone else’s reading in a vain effort to attract the attention of Mr Darcy. Again, shift your gaze from Jane Austen’s face slightly to the left and you find a young woman in Regency dress, apparently writing at a table on a writing-slope. This image does identify Austen as a writer, but in distinctly amateur and even secretive mode; her face is averted, her shoulder turned to the viewer, and her arm cast protectively across her work.

There is, in short, something unusually shifty about this depiction of a writer, and it is confirmed by the image of the house to the left of the portrait. This is not an image of Chawton Cottage, the place where Austen lived with her mother and sister between 1809 and 1817 and wrote most of her works.

Instead, this is Godmersham Park in Kent, home to one of Jane’s brothers, who was adopted as a child into a wealthy family and eventually inherited this estate. The biographical record suggests that Austen spent a total of some ten weeks in this house on a number of visits, during which she made use of the library. This image is based on a contemporary engraving, and the horse-drawn carriage clearly engaged in a pleasure outing that trots briskly through a Capability Brown landscape and over the words ‘Ten Pounds’ is designed to underscore the status of Godmersham as a gentleman’s residence. That said, the image, drawn from an expensive collection of engravings entitled History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent (1798) that would have graced just such a country-house library, also irresistibly recalls Elizabeth Bennet’s tour with her uncle and aunt, which took in Darcy’s seat, Pemberley, supposedly set in Derbyshire. This is the setting of what is probably nowadays the most famous single episode in the Austen canon, the moment charged with the shock of sexual desire when Darcy emerges wet-shirted from swimming in the lake and comes face to face with Elizabeth.

This, as it happens, is a scene which Austen herself never scripted. It is a modernization by Andrew Davies for the BBC in 1995 of Austen’s own erotics. In Austen’s version, Elizabeth jokingly says that she is not sure when she first fell in love with Darcy ‘but I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley.’ Many a true word is disguised in Austenian jest – when she does indeed see Pemberley for the first time, the narrative dryly records: ‘at that moment she felt that it might be something to be mistress of Pemberley.’ What is truly sexy in Austen’s fiction is landed money. W.H. Auden famously remarked of her fiction: ‘It makes me most uncomfortable to see/An English spinster of the middle-class/Describe the amorous effects of “brass”.’ Darcy’s worth is explicitly set at £10,000 a year, and, whatever else Pride and Prejudice may be about, it is about money, its desirability, and the way of life that expresses it and is secured by it.

One of the things that the fashion for filming Austen’s novels over the last twenty years has tended to obscure is Austen’s own social status; she did not herself belong to the landed gentry – that is to say, to the class of the owners of such houses and estates as Pemberley, Netherfield, or Rosings. Instead, like Elizabeth Bennet, she belonged to what has been called the ‘pseudo-gentry’, a class of upper-professional families living in the country (clergymen, barristers, army and navy officers, retired merchants), none of whom had access to the renewable and selfsustaining wealth of land, but depended on earned incomes. That class sought to be taken for gentry by the acquisition of the manners, education, and markers of station, but did so on limited incomes, which depended precariously on the life, health, diligence, and probity of the male breadwinner. As the critic Edward Copeland remarks: ‘As a consequence, money, especially money as spendable income, is the love-tipped arrow aimed at the hearts of Jane Austen’s heroines and her readers…’

Thus the new £10 banknote is both truthful and untruthful about Austen. Like much contemporary popular culture, it does its best to turn her from a writer of classics into one of her own rom-com heroines, preferably Elizabeth Bennet. But it also admits, almost without meaning to, Austen’s own interest in money, her sense that a regular, solid income calculated in multiples of ten is the true basis of romance.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews