3.1 John Walsh and the London audience

Walsh began publishing music in London in 1695, at a time when there were few rivals to his work in this area. His prolific predecessor, the music publisher John Playford (1623–c.1686/87), had left behind a market for music publications which he had nurtured and dominated from the middle of the seventeenth century. Walsh published repertory on an unprecedented scale for London, including works by both English and continental composers. Until around 1730, he worked in partnership first with the publisher and violin maker John Hare (d.1725) and later also with Hare’s son Joseph (d.1733). Walsh was an extremely astute businessman and his output covered a wide range of secular repertory that would appeal to the London audience, including songs, operas, instrumental music and instruction books. He eventually became the principal publisher of Handel’s music. His son, also named John, continued the family business for another thirty years after his father’s death (Kidson et al., 2014).

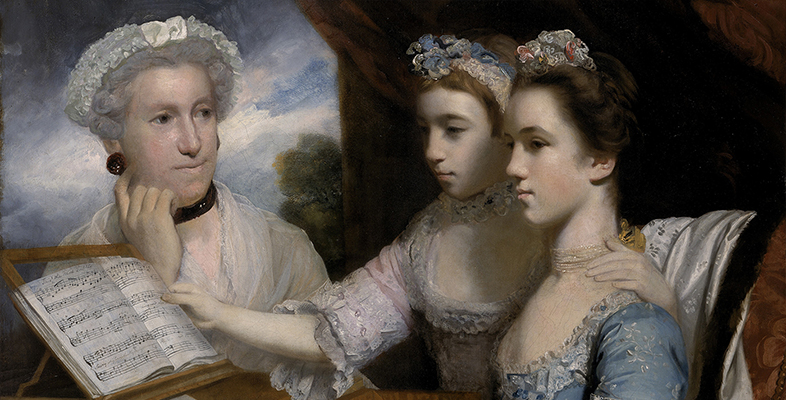

The success of Walsh’s music publishing business was due to the generally favourable circumstances for music-making in London during the early eighteenth century. Of all the major music centres of the period, it was London where the first regular public concerts took place in 1672, and this environment not only attracted the best professional musicians of the period to the British capital, it also allowed amateur music-making to develop, at home and in music societies. Walsh’s publications were therefore aimed at the section of the London population who would participate in musical performances. In the early years of the eighteenth century, the music-buying public was mainly the wealthier, privileged classes who could afford to attend concerts and go to the opera, and who were willing and able to purchase editions of their favourite music. Later in the eighteenth century, the market began to expand as repertory became more accessible to the middle classes (Edwards, 1976, pp. 57, 59, 83).

Walsh’s publications clearly reflect the wishes of his affluent customers. Besides the popularity of music composed in and for London (such as by Henry Purcell, 1659–1695, and later Handel), musical tastes of the time were dominated by the aristocratic love of Italian culture – many had visited cities such as Venice and Rome on their ‘Grand Tours’ of Europe, and returned to London with great enthusiasm for the music and musicians they had heard in Italy. This taste for Italian music was further demonstrated by the many Italian musicians – singers and instrumentalists – who were welcomed to the British capital. It was this demand for Italian music, together with a love of novelty – the London concert-going public were keen to witness anything ‘new’ or ‘different’ – and the fondness for amateur music-making, that Walsh tried to reflect in his publications.