Origins

Many aspects of what we now call ‘Carnival’ were brought over to the UK in the early twentieth century. Cardiff’s Butetown Docklands was at its height at the time. A lot of traffic was coming from West Africa and the Caribbean, and all over the world.

In Wales, there were already traditions, such as Mari Lwyd, where people would dress up and sing or tell each other stories, going from household to household. People with makeshift instruments would perform in the streets and were paid in food and drink. These elements of Carnival were already there, over a hundred years ago.

As well as this, a travelling fair used to park up in Loudoun Square in Butetown in the winter. So, there would be a winter fair every year within the local community.

Mardi Gras and Butetown’s ‘slum clearance’

Fast forward to the mid-1960s: Cardiff’s Mardi Gras was set up as a philanthropic gesture by politicians and other powerful figures in Cardiff for the ‘poor people of Butetown’.

This coincided with Butetown’s ‘slum clearance’ programme. The community was being unsettled, so Mardi Gras may have been a palliative response to that. The event’s subheading was International Caribbean Carnival. That ran for a few years, before being cancelled by the Council.

Responding to racism: the rise of Carnival

In the 1970s, Butetown Youth Club used to enter Caribbean-themed floats in the Lord Mayor’s Parade in Cardiff. One year, there was an incident were someone in the crowd made racist comments. This resulted in a confrontation. However, it was the Youth Club who were punished, and banned from the Parade, for responding to the racism directed at them.

The Youth Club leaders decided they would hold their own event. The elders of the community were aware of the cultural significance this would hold, so specifically chose for it to be a carnival. There is something inherently cultural in the carnival element of it.

Also, around that time, black culture suddenly had its own space. The growth of the carnival was happening across the UK. St Paul’s Carnival in Bristol and Notting Hill Carnival in London, all appeared in the 1960s, but took off in 1970s and began to have more of an impact on the general culture.

Riots in London

Butetown Carnival was rained off one year, so a group of us went to Notting Hill. This happened to be the year of the 1976 riots. We were all safe, but when we got back, the community leaders and elders decided that Carnival would be a permanent fixture in Butetown, so that we didn’t have to go away to find our culture.

‘The biggest cultural event in Cardiff’

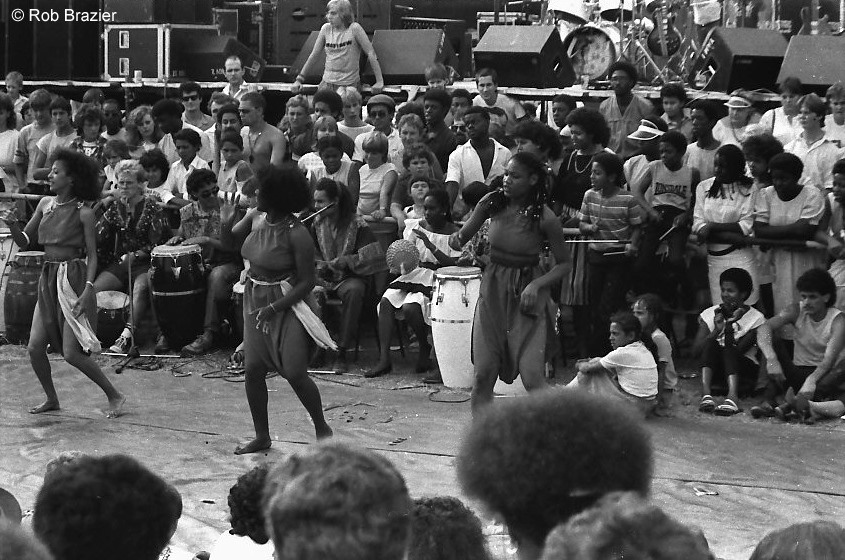

From 1977, Butetown Carnival became enshrined as what we know it as today. Over the next decade it grew in popularity. By the mid to late 1980s, it was the biggest cultural event in Cardiff. It had daily attendance of 25,000, at a time when the local population was around 4,000.

You see the kind of impact we had across the wider city. People even came down from London, to our Carnival. Our response to being excluded from the Lord Mayor’s Parade was to put on the most inclusive cultural event in Cardiff, possibly Wales.

Taking back Carnival

Despite its success, Butetown Carnival closed due to financial complications in the late 1980s. The company behind Cardiff Bay’s redevelopment tried to revive Butetown Carnival. However, the people of Butetown weren’t happy with it being taken out of our hands, so a local group, including myself, stepped in to save Carnival. We called ourselves Tiger Bay Community Arts.

My cultural interest in Butetown’s history came from the community and elders around me. People used to show pictures and make things like paintings. Olwen Watkins, a local schoolteacher, was my mentor. A lot of her principles and the conversations we had are embedded in my own philosophy. She told me to stop complaining about the things that were happening in the community and go out and do it myself.

We inherited some funding, but after three years, the money ran out. We managed for another year, but the community became disheartened. We found ourselves in competition with other cultural events in Cardiff, that had much more funding, and often overlooked the black artists and performers right on their doorstep. In the end, Carnival just stopped happening.

‘To paint a more positive picture.’

However, six years ago, we decided it needed to come back. We aimed to do something with nothing, to paint a more positive picture of Butetown. Other organisations coming in had disempowered us, but we could still do Carnival.

We’d all been split up. Ethnic profiling was happening in housing allocation. Borders were created around us, which caused problems of rivalry between different groups. Suddenly, there was a Caribbean community, a Somali community, a Yemeni community, instead of a collective Butetown identity.

Something like Carnival – music, food, dance, colour, costumes, family – that’s bound to bring community together anywhere in the world. Butetown Carnival is about celebrating the different cultures of our community, but, at the same time, we’re fighting against the siloes that have been created around us – and it’s working.

Carnival has this fire, and you can’t take that away from us.

Bringing Butetown together

We keep feeding into this image of poverty and hardship. Art and literature love dystopia, so whenever Butetown is revisited in these forms, it’s always about the community that died. However, we, the local people, have started buying into those stories ourselves.

We need to be careful and clear about the way things are depicted in the minds of the next generations. Everybody is telling the same old stories of what Butetown was, what it’s lost, what we can’t do. It’s not that certain problems don’t exist, but what we can do says ten times more.

Someone asked me how I felt at the first Carnival in 2014. I looked around and clusters of people were having conversations. In the context of Butetown and the social upheaval it’s been through, to turn around and see that was brilliant.

‘The now is ours too’

With regeneration, thousands of new houses surround Butetown. However, some parts of the development have been there for 30 years now. I was walking past the Wales Millennium Centre with my granddaughter, who was three at the time. She pointed to it and said, ‘That’s where we do Carnival,’ and, in her memory, that is where it’s always been. That was really profound for me. We must remember, the now is ours too.

This year was very different due to the Coronavirus pandemic. We planned to deliver a series of events and creative workshops over 12 months to communities across Cardiff. With lockdown, we couldn’t do this, so we commissioned the artists leading the workshops to work on their own creative projects at home. We then made short films for each of the pieces.

We also held some pop-up performances outside the Senedd and Wales Millenium Centre. We were able to get a local youth dancing group some professional work. One of the girls said dancing there meant a lot because Butetown is where her grandma lived. That was again very profound, as she saw the same value in the place as I do.

Investing in community

I’m conscious there is still a lack of community representation in Butetown Carnival. In terms of traditional costume and puppet making, or steelpan playing, there are currently no artists from Butetown. We need to bring these skills back, invest them with value and teach younger generations, so that they want to continue these traditions going forward.

There are also those of us who are falling in the gap of ‘rageism’ – racism and ageism. In modern Wales, there are lots of projects for young people of colour. But there is a large group of us who’ve been excluded for decades. We want to bring young people into what we’ve built, as their community. The skills, the talent, the heart is there, it just needs to be put into practice. You must invest longer term. People aren’t young forever.

I’ve worked with a lot of individuals who’ve shown interest in what we’re saying and, the next day, don’t want to know us. We’re addressing this exploitation as a matter of justice and quality. We tell our stories better. We are generous. Work with us, and you’ll get the whole story, not half of it.

Reclaiming our space

Butetown Carnival has always been viewed as a black music event. Before the Black Lives Matter Movement, before MOBO was a term, this was seen in a pejorative sense. Now, twenty years on, the world view is changing – a black music event is finally recognised as legitimate.

We originally put on the Carnival in Canal Park on Loudoun Square because nobody could stop us there. The parade usually starts at the waterfront at Mermaid Quay, which historically used to be the Butetown Docklands, and ends at the park. In future, I would like to reverse this, so that we start at the park, and end the parade by presenting our Carnival to the world, reclaiming our space, where our story began.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews