1 The changing position of women in the home and workplace

How, when and why did women get the vote? Your work on the suffragettes later in this course will help to answer these questions, but first it is important to reflect on the pre-history of the campaign.

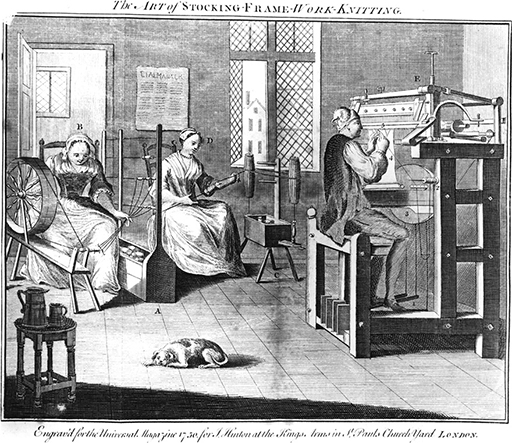

Prior to the later eighteenth century (about 1760), the majority of the population had lived in the countryside and most manufacturing had taken place within individual and poor households. Wives and children had assisted in making goods for the market. Married women had played other economic roles too – acting, for example, as midwives, washerwomen or casual field hands.

Many historians and sociologists believe that industrialisation in Britain between about 1760 and 1830 brought profound changes in household organisation and, as a consequence, the economic roles of women. According to this view, household production was destroyed, and home and work became separated as workers moved into factories in the towns. The home became almost exclusively a place where children were reared and families fed. In wealthier, middle-class households the family became a haven for its members and, more particularly, for the male breadwinners. In the nineteenth century, the middle-class family withdrew from its servants (who were thrust either below the stairs or in the attic), its workplace (now located at a distance) and its community (living far from its workforce). ‘Domesticity’, in this model, was a luxury many could not afford.

There was also now a rapidly increasing number of poor men and women who had to put themselves up for hire because they could not earn enough from their own land to survive or support families. Some moved to the towns to find work, others to the coalfields. Many were on poor relief or entered the workhouses. The factories came later – in the second half of the nineteenth century in many cases. They drew both male and female labour; conditions were appalling and workers had few rights.

It was the propertied men of the upper and middle classes who had the vote and who, through representation at both local and national levels, shaped policy and legislation. The belief in ‘virtual representation’ explains many of what we today regard as incongruities in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century suffrage. This applied to a society in which it was believed that the master in the workshop or the employer in the factory or mine stood in the same relationship to their workers as a father did to his family. The father, or patriarch, understood the needs of his children and acted in their interests. Likewise, the master and employer understood the needs of their workers and also acted in their interests. This view of society, as organised paternalistically, prevailed until well into the twentieth century, if not beyond. If one believed in paternalism, then depriving working men and women of the vote was not incongruous at all.

In reality, men often didn’t earn enough to support their families without help from the wages of wives and children. Setting aside the predicament of the very poor – the unemployed or casually employed labourers and their families – who led a precarious existence and often moved in and out of the workhouses, there were many ‘respectable’ families from the working class and the lower middle class who relied on a combination of male and female labour and/or wages.