About this article

Focusing on three Cajun tales by Zachary Richard, this article explores the interrelation of Cajun culture and the transnational space through the lens of “migrating literature.” The interrelation of literature and migration is visible on several levels: first, the texts literally “migrated” to Montreal, Quebec, for publication purposes; second, the tales are literatureabout migration; and third, other “foreign” literary texts and allusions to historical events “migrated” into the tales. Considering the meaningful settings- Louisiana, Canada, France - as well as the overarching themes of displacement and migration, the tales reveal themselves as allegories of the Cajuns’ history. Bringing together different regions, the tales respatialize the Acadian diaspora in a geo-cultural imaginary space and undergird the transnational connection.

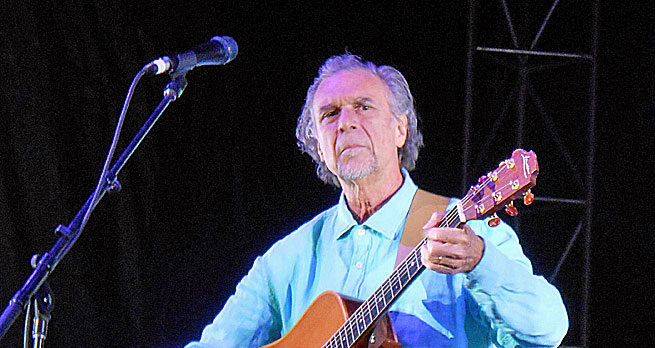

Zachary Richard

Zachary Richard

Introduction

The history of the Cajuns, the French-speaking minority living in Cajun Country, or Acadiana, in southwest Louisiana, is a story about transnational migration which reaches 400 years into the past. Eighteenth-century Acadian history, especially, features prominently in the Cajuns’ collective consciousness today. In Cajun Country, local legend has it that when the Cajuns’ ancestors, the seventeenth-century French colonists called Acadians, were expelled from their homeland Acadia on the east coast of Canada in 1755 by British and New England forces, a swarm of lobsters accompanied them into exile and later to Louisiana. Boarded on ships bound for the New England colonies, France, and the Caribbean, the deportees were scattered along the Atlantic seaboard. According to the legend, the miserable conditions during the so-called Grand Dérangement(“Great Upheaval” in English) took such a toll on the lobsters that by the time they arrived in Louisiana, they had shrunk to the size of crawfish. The origin of the legend remains unknown, but its first written evidence appeared in the 1970s when the Cajun Renaissance, an ethnic grassroots movement, was in full swing. With the booming tourist industry in Louisiana promoting Cajun culture, the legend was printed on souvenirs and restaurant menus, and started to circulate around southwest Louisiana.

In contemporary Louisiana, the lobster-turned-crawfish legend is still very much present as attests L’histoire de Télesphore et ‘Tit Edvard dans le grand Nord, the second tale in a trilogy by Cajun poet and singer-songwriter Zachary Richard, which also includes Conte cajun: L’histoire de Télesphore et de ‘Tit Edvard and Les aventures de Télesphore et ‘Tit Edvard au Vieux Pays. Likewise, Cajun culture and French in Louisiana seem very much alive, for the tales are written in French with Cajun idioms and indicate a distinct Cajun perspective. They contribute to the littérature cadienne, a francophone Cajun literary genre which emerged in the 1980s, succeeding the Cajun oral tradition and continuing the French Creole literary tradition which flourished in nineteenth-century Louisiana. The majority of those new francophone texts, however, are published in Montreal, Quebec, not in Louisiana. This also applies to Zachary Richard’s tales, which deal with the adventures of ‘Tit Edvard, a crawfish, and Télesphore, a turtle, from Louisiana who experience various displacements and go through many adverse conditions before finding their way home.

In focusing on Richard’s three Cajun tales, this article explores the interrelation of Cajun culture and the transnational space Richard creates in his tales. After a brief outline of the genesis of the Cajuns and the state of francophone literature in Louisiana, I will focus on the multiple representations of migration in the tales. First, I will analyze how such elements as landscape, language, and the past contribute to a Cajun sense of place and belonging. Significantly, two characteristics determine the Cajuns’ lives today: self-assertion in a dominant society which is markedly different and a memory of the past. In emphasizing the singularity of Cajun culture, the Cajuns distance themselves from the omnipresent American mainstream culture. Indeed, the alien surroundings and unfamiliar creatures that ‘Tit Edvard and Télesphore face evoke a sense of Otherness.

Also, Richard’s multiple allegorical representations of the Grand Dérangement mirror the Cajuns’ strong connection to the past and turn the tragic event into a leitmotif. I will then explore the transnational outlook of the tales. Precisely because the Cajuns’ experience has been one of expulsion and migration, place, culture, and the past play a crucial role as means of orientation and carriers of memory in the Cajuns’ collective consciousness. At the same time, though, the characters’ exemplary tolerant attitude and adaptability convey the image of a permeable culture, a culture which blends with other cultures through a process of osmosis and relies on transnational exchanges. This is particularly evident in intertextual references to Native American and African mythologies, to French literature, as well as in allusions to decisive historical events. This borrowing from both the cultural memory as well as the “memory of literature” of other cultures in Richard’s tales provide a good illustration of Astrid Erll’s concept of “traveling memories.”

A specific feature of “transcultural memory,” which is “a certain research perspective… directed towards mnemonic processes unfolding across and beyond cultures”, it draws on James Clifford’s concept of “traveling cultures” to describe how memory processes are always in flux and transgress boundaries of time and space. For the purpose of this article, I propose the concept of “migrating literature.” In Richard’s tales, the interrelation of literature and migration is visible on several levels: first, the texts literally “migrated” to Montreal for publication purposes; second, the tales are literature about migration; and third, other “foreign” literary texts and allusions to historical events “migrated” into the tales. Thus, Richard’s three animal tales are a prime example of “migrating literature” and of a transnational exchange. They bring together different regions, respacializing the Acadian diaspora in a geo-cultural imaginary space and undergirding the transnational connection.

In reorienting the tale’s Cajun space towards other countries and fixing his vision in a written form, Richard ensures the continuing existence of Cajun culture. I argue that this new outlook transcends general assumptions about Cajun culture—engendered by its folklorization—and creates a transnational space. Richard, extending the Cajun space to Canada and France, shows that a dynamic and evolving culture is necessary for the preservation of Cajun culture. Most important, he deems the establishment and maintenance of the connection to the francophone world as essential for the survival of Cajun culture.

Stories of Migration

The Cajuns can look back on an eventful history of wandering around the Western hemisphere. This transnational migration actually started in the early seventeenth century, when French colonists from the Centre-Ouest region traveled to the east coast of Canada, settled along the Bay of Fundy, and founded the colony of Acadie in what is today New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Far removed from the world affairs for most of the century, they eventually became pawns in the French and Indian Wars between the two imperial powers Great Britain and France. While the French largely neglected the colony in North America, the British, despising the Acadians for their French background and Catholicism, coveted the fertile lands the Acadians had gained from their arduous dike building.

Repeatedly, the Acadians refused to swear an unconditional oath of allegiance to the British King, emphasizing their wish to remain neutral. This noncommittal stance earned them the name of French Neutrals and finally contributed to their fateful dispersal, the Grand Dérangement. In 1755, an order was issued to deport the Acadians to the New England colonies, France, and the Caribbean. Between that year and 1763, thousands of Acadians were expelled from their homeland, separated from their families, and subjected to inhuman conditions on the deportation ships and in their lands of exile. Despite the widespread scattering, the Acadians’ strong communal ties kept small communities together. Around 1765 a group of Acadians, hearing of a land to settle where French was spoken, traveled to Louisiana by way of Saint Domingue (today Haiti) to build a new Acadia. They settled along the bayous of the Mississippi River and, by and by, were joined by other refuge-seeking Acadians. In intermingling with other ethnic groups, they assimilated various cultural traditions of their neighbors. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Acadians had become the Cajuns, an ethnic group with a distinct hybrid character exemplifying the constant exchanges between the various cultures existing in Louisiana for over two centuries. Today, Cajun culture boasts influences of French Creoles (French colonists born in Louisiana), Spanish, Native Americans, African and Caribbean slaves, Anglo-Americans, Germans, and Italians.

Up to the middle of the twentieth century, most Americans knew the story of the Acadians thanks to Evangeline, an Acadian literary heroine who became an American icon. The epic poem Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie (1847),written by New England poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, describes the separation of the two lovers Evangeline Bellefontaine and Gabriel Lajeunesse from Grand-Pré on their wedding day by British and New England forces. Evangeline’s subsequent search for Gabriel leads her to Louisiana, to the Acadians’ nouvelle Acadie. The story ends with Evangeline, aged and a Sister of Mercy, at Gabriel’s deathbed in Philadelphia. This Acadian saga became an immediate success in both the United States and Canada, and the wretched Acadians, symbolizing fortitude and endurance, entered the American collective memory. Its success notwithstanding, Longfellow’s poem is anything but a truthful account of Acadian history as it contains numerous inaccuracies and dissimulates historical details. And yet, this rose-colored account not only contributed to the strengthening of the American national sentiment of the time; the Cajuns, for want of a founding myth, also readily accepted the New England poet’s retelling of the Grand Dérangement and appropriated it as their own foundational story. Apart from the attraction that the virtuous and strong Acadians and saintly Evangeline exercised on the American public, the myth also offered the Cajuns the opportunity to distance themselves from the American foundational myth of the Pilgrim Fathers.

And yet, with the turn of the twentieth century, the growing Americanization movement began to greatly affect Cajun culture. The law of 1921, which had prohibited French in public schools, the two World Wars, the discovery of oil in Jennings, Louisiana, and the progressive construction of an infrastructure in Louisiana all contributed to the Americanization of Cajun Country and were the main causes for the demise of French in Louisiana. Unable to resist the lure of the American mainstream and with it the English language, the Cajuns gradually abandoned their French heritage.

However, encroaching Americanization was slowed down by the Cajun Renaissance, which coincided with other ethnic revivals in the 1960s. This emancipation process epitomizes the Cajuns’ growing awareness of their threatened culture. The positive echo Cajun music received at the Newport Festival in 1964 was followed by a growing academic interest in Cajun culture and cultural preservation efforts Thanks to revisionist works concerning Cajun history by scholars of Cajun origin at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette, attention was drawn to the culture’s uniqueness and especially to the real events surrounding the expulsion of the Acadians. To counter untruthful and stereotypical depictions of the Cajuns, historians started debunking the Evangeline myth—to the profit of other myths cropping up in Cajun Country.

A crawfish

A crawfish

Against this backdrop, the lobster-turned-crawfish legend and Richard’s tales can be considered not just counternarratives to the American myth of the Pilgrim Fathers, but also to the Evangeline myth, invented by a New Englander who had never been to either Nova Scotia or Louisiana. By appropriating the counternarratives as their founding myth, the Cajuns distanced themselves from American mainstream culture even further and strengthened their links to francophone Canada through academic exchanges and the establishment of the Acadian World Congress, held for the first time in 1994. At the same time, Louisiana witnessed the emergence of such Cajun poets and storytellers as the prolific Cajun singer-songwriter and poet Zachary Richard, who engendered a literary tradition which renewed that of the nineteenth-century created by French Creole authors such as Sidonie de la Houssaye, Alfred Mercier, and Adrien Rouquette. As a matter of fact, although Richard’s original Cajun tales have strangely been bypassed by scholars, they testify to the vitality of Cajun culture.

(Re)locating Cajun Culture

Clearly, the legend mentioned in the introduction reflects the Cajuns’ identification with the region of Acadiana:xi the crawfish functions as the link between the place and the people. It comes as no surprise that the metaphorical solidarity between the Cajuns and the crawfish culminated in the adoption of the crawfish as the Cajuns’ very own mascot, symbolizing both Cajun power and ethnic pride.xii Similarly, Richard’s tales are grounded in Cajun space: the crawfish, representing the Cajuns, and the yellow-bellied turtle are typical creatures of southwest Louisiana’s fauna. Set in a predominantly natural environment, the tales are inscribed in the genre of regionalism as they present places that have “‘escaped’ the dubious improvements of a stronger and more integrated urban society”.

The frequent references to such identity markers as landscape, language, and the past create an unmistakably regionalist tone which is accentuated with the change of settings to foreign places. Significantly, it is the transnational wanderings and the experience of foreign cultures which help locate Cajun culture. As suggested by their titles (Conte cajun: L’histoire de Télesphore et de ‘Tit Edvard, L’histoire de Télesphore et ‘Tit Edvard dans le grand Nord, and Les aventures de Télesphore et ‘Tit Edvard au Vieux Pays), the tales seem to trace the Cajuns’ roots back to their origins: Louisiana, Canada, and France are the featured destinations and create a geo-cultural triangle. Considering the meaningful settings as well as the overarching themes of displacement and migration, there is no doubt that the tales allegorize the Cajuns’ history. Besides the attachment to place, the legend and the tales stress the importance today’s Cajuns ascribe to the past. The forceful dissolution of the Acadian community, in particular, is one of the most prominent characteristics of the collective memory of the Cajuns today.

It is important to note that Acadia as a region ceased to exist after the break-up of the Acadian community in the mid-eighteenth century, and remains absent from official maps. Still, Acadia has not disappeared from discourse: through literary references and ongoing memory work such as commemorative celebrations, it has become an imaginary space—and another site of memory which connects all Acadians scattered around the world. Although an abstract geographical space, Acadia seems to exemplify Douglas Reichert Powell’s statement concerning “sense of place”:

‘senses’ of place and region are not so much essential qualities, imparted by singular events, practices, or topographical features, as they are ongoing debates and discourses that coalesce around particular geographical spaces. Furthermore, it is by looking at those features of a place that seem, at least superficially, to be the permanent stable markers of its identity that we can begin to see the dynamic, evolving, and rhetorical qualities that create and sustain what has often been taken (reductively) to be an ineffable or ethereal, sensory property: the ‘sense of place.’

Acadia today exists in Cajun Country and in Maine in the United States; in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island in Canada; in South America and the Falkland Islands. It is the Acadian diaspora, commemorating the Grand Dérangement and celebrating Acadia’s imaginary continuity. The “dynamic, evolving, and rhetorical qualities” Powell mentions are most evident in the depiction of the expulsion in Richard’s tales: the allusions to the Grand Dérangement and Acadia develop with each unfolding tale, in different locations, from a symbolic reference to an explicit reenactment of the event.

Conte cajun: L’histoire de Télesphore et de Tit Edvard (1999)

In Richard’s first tale the two protagonists Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard are brought together during a hurricane. Unfortunately, little, helpless ‘Tit Edvard has not only lost his parents, but he has also lost one of his claws. Télesphore promises ‘Tit Edvard to help him get the claw back. They start out on an uncertain journey during which they are joined by four frogs—Jean, Jacques, Pierre, and Paul—and two grasshoppers—Henri and Madame La Sauterelle. They find themselves in a number of dangerous situations, but are helped by other friendly animals crossing their path, such as the spider l’Araignée Arc-en-ciel and the alligator Monsieur Le Coteau Qui Parle, a name the group gives to what they think at first sight is a “speaking hill.” Their encounter with l’Araignée Arc-en-ciel, the spider with magical powers who is supposed to solve the problem of the missing claw, is the tale’s climax. Unfortunately, the spider cannot help them and the group understands that ‘Tit Edvard’s claw is lost for good. Having failed at their endeavor, the companions return home, but not without realizing, with the help of the alligator’s wise words, that their journey has also had some benefits: not only have they forged individual identities, but they now possess a collective memory with which they can identify as a group.

The regionalist tone of this first tale results from allusions to Louisiana and, more specifically, Cajun culture, which help construct a Cajun sense of place. Richard’s animal characters are inhabitants of the Wetlands, the coastal marsh and swamp region in South Louisiana. Despite the scarce information about the exact setting, it is possible to identify the space the companions are traveling through. Landscape specificities such as cheniers or bayous, emblematic features of Louisiana and very often linked with Cajun culture, function as geo-cultural codes and give a visual picture of the spatial setting of the tale. The animals’ northward journey to find l’Araignée Arc-en-ciel clearly hints at an invisible force driving them to a home, distant in time and space. The direction the companions follow roughly corresponds to the direction to Acadia.

Acadian author Antonine Maillet wrote about the perilous journey back to Acadia in her novel Pélagie-la-charette, which won the Prix Goncourt in 1979. The novel’s heroine, Pélagie Bourg dite Le Blanc, is deported to Georgia from where, after years of misery, she travels all the way back to Acadia with her cart. Not so the eight companions in Richard’s tale: their northward journey remains incomplete. Although it is not their intention to go back to the lands of their ancestors, they have a similar goal: to look for something lost. Indeed, the cast-out Acadians had lost their land and possessions, and went on a journey to find what they had lost. Some of them, like Pélagie, went back to Canada after years of exile in the New England colonies and rebuilt their homes. Others arrived in Louisiana and founded a new Acadia there. Similarly, when the companions come back, they build Edvardville. This allusion to Acadian history, though slight, lays the foundation for the retellings of the Grand Dérangement in the other two tales.

L’histoire de Télesphore et Tit Edvard dans le grand Nord

The second tale is set in the “big North,” in Quebec and New Brunswick, a territory unknown to Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard. As in the first tale, their adventure starts with a tragic event: on a peaceful fall afternoon, Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard are resting in the sugar cane fields when they are suddenly picked up by a harvester and catapulted on a hay bale into the atmosphere. Their attempt at jumping off the bale at the right time fails, and they end up somewhere in Quebec, instead of Louisiana. Fortunately, they are taken in by a hospitable beaver couple, Mario and Maria, who introduce them to the country’s—surprisingly familiar—culture. However, Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard feel the pull of home. With the help of René le Raton, a raccoon, and Louise L’Orignal, a moose, the two companions reach a city where they hope a snowplow will propel them back to Louisiana. The experiment fails: Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard land a little further south, in New Brunswick. Once more, help is nearby: Rose La baleine, a whale, leads them into “Homardie,” the land of the lobsters, who reveal to ‘Tit Edvard the ancestral connection between the crawfish and the lobsters. The lobsters, unfortunately, cannot help the two friends, but a swarm of ravens, on their south-bound journey, finally bring them back to Louisiana.

In Canada, Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard are struck by the different climate and unfamiliar creatures. The beaver, Canada’s national symbol, the moose, and the lobsters contribute to the construction of a Canadian space which contrasts with the culture of the two friends. Most upsetting to them is the feeling of Otherness and the fact that nothing looks familiar. ‘Tit Edvard

does not recognize the trees. All the leaves have fallen, leaving the branches naked. Moreover, there are no green oak trees and no magnolias which give the Louisiana landscape a touch of greenness even in the midst of winter. Instead, ‘Tit Edvard sees black spruces and pine trees which do not resemble the big white pines of the Louisiana forests.

No wonder that the first snow comes as a shock to them, who are used to heat and humidity. When they encounter the beaver couple Mario and Maria, the two friends notice a similarity to the muskrat in Louisiana, although they are bigger and their tail looks different. However, soon enough the four animals bond and compare the fauna, flora, and cultural specificities of their respective countries. ‘Tit Edvard’s and Télesphore’s Canadian experience not only strengthens their sense of Cajun, or Louisiana identity, it also expands their horizons of knowledge.

The pull north alluded to in the first tale is concretized in the second tale. Set in the “big North,” the sequel focuses especially on Acadian history. After the failed attempt to reach Louisiana with the snowplow, ‘Tit Edvard and Télesphore land in Homardie, the land of the lobsters, which echoes the former Acadie thanks to its homonymous ending and comparable setting, for it is located in New Brunswick. Hermance le Homard, the chief of the lobsters, enlightens ‘Tit Edvard about his past: he is a descendant of the French lobsters! Just like the Acadians, who left France to live a better life in Canada, the lobsters left France and arrived on the banks of northeast Canada. There follows a detailed history of the lobsters, a perfect allegory of the Acadian deportation—the legend of the lobsters turning into crawfish. It is worth noting that Hermance calls the incident “Grand Déplacement” which undoubtedly constitutes a reference to the historical Grand Dérangement of the Acadians. Like Acadia, Homardie has ceased to exist for the lobsters: “Today, here… is not Homardie anymore, except for in our hearts”. The tale then presents a double displacement: ‘Tit Edvard’s and Télesphore’s own displacement and the reference to the dispersal of the lobsters, which parallels the Grand Dérangement.

Les aventures de Télesphore et Tit Edvard au Vieux Pays (2010)

The third installment resumes the narrative about Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard. Transferring the setting to Europe—more precisely, to France—Richard makes the transatlantic connection—Louisiana, Canada, and France—come full circle. The story opens with a tragically familiar scene: Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard, enjoying the first sunny days of the approaching spring in the waters of a rice field, are caught by a fishing boat and taken to France. In contrast to the previous tales, the two friends are not the only victims: they find themselves amidst a swarm of crawfish with whom they will go through a number of afflictions. Jammed in the dark and foul-smelling bilge, with no food or water, the captives endure both a distressing and emotional oversea trip. After landing in La Rochelle, on the west coast of France, they manage to escape with the help of Jacques Cocorichaud, a rooster from the region of Bresse. Sadly, in the big commotion Télesphore is left behind.

The group of crawfish and Jacques start an errant life in the woods until they are arrested by the “patrouille sauvage,” a wildlife patrol controlling the border between the world of the domestic animals and the world of the wild animals. The rooster is returned to the world inhabited by the domestic animals, but the crawfish have to remain in what resembles a refugee camp. They are visited by an assigned counsel, Claude Tomate de la Beletterie, a weasel, who declares that she will find a solution to free them. Since she cannot understand the crawfish, she is helped by an interpreter who turns out to be Télesphore, now a political refugee and free. With her legal training, Claude issues a request to have the crawfish also recognized as political refugees. In order to succeed, it is necessary to prove that the crawfish are the descendants of a group of crawfish who mysteriously disappeared from France in 1632. Télesphore goes on a long quest to find the documentation needed and returns successfully. The crawfish are finally offered sanctuary.

Although the group from Louisiana grapples with the different cultural habits they encounter as, for example, the French custom of cheek kissing , it is the seemingly strange language of the French animals which disconcerts them most. Of course, apart from landscape and cultural habits, language is another major identity marker which contributes to creating a sense of identity. ‘Tit Edvard’s and Télésphore’s linguistic experiences recall the debate about which French is to be promoted in Louisiana: Standard French or vernacular French, i.e. Cajun or Creole French, or other dialects? Already in Canada, the two animals notice the slight differences in vocabulary and accent when they hear the beavers speak French. The most notable scene, however, occurs in the third tale when the captive crawfish and Télesphore, upon landing in La Rochelle, meet the rooster Jacques Cocorichaud, representing France. An arrogant and self-centered know-it-all, he treats his fellow animals haughtily and without respect, especially when they speak French improperly. For him, there is only one correct way to speak French. In contrast, wise Télesphore, a polyglot, notices that Jacques’ French resembles the spoken language of the fowl in Louisiana and that there is a marked difference of accents. As to the rooster, he makes no secret of his contempt for the Louisiana French accent: with a disdainful look he interrupts Télesphore and impertinently corrects his articulation. The turtle, who tries to contain his anger, cannot help making a statement in real Louisiana dialect: “Si tout quelqu’un causé pareil, li moun vini ben moins intéressant”. Jacques is at a complete loss as to what this means and Télesphore readily provides a translation: “If everybody spoke the same way, the world would be less interesting”

The discussion between Jacques and Télesphore reproduces the controversy about the French language in Louisiana. Of course, it echoes Zachary Richard’s own view of Cajun French and Cajun culture. Cultures, and languages for that matter, are in constant flux and foreign influences are a means for rejuvenation. Considering the precarious state of French—Cajun French is slowly, but surely disappearing—Richard shows that French is alive in Louisiana and that it must be preserved. Richard’s narrator uses Standard French, arguably to reach a wider audience, but includes such Cajun idioms as “ouaouaron” or “plantin,” which are explained in a glossary at the end of each tale. Richard’s tales thus present seemingly disparate cultures, for although Canada and France represent difference and function as foils for Louisiana, they are also mirrors showing similarities with Louisiana. Stephanie Foote notes that “[b]ecause it is a form that works to preserve local customs, local accents, and local communities, regional writing is a form about the presentation of difference”). With each displacement, ‘Tit Edvard and Télesphore face different cultures, but are reoriented by familiar cultural elements, as for instance the French language or animals.

Ultimately, the third tale develops the diasporic leitmotif even further, for it is a veritable reenactment of the Acadian tragedy: together with other crawfish, ‘Tit Edvard and Telesphore are captured and put on board a ship bound for France. They experience their very own dérangement. Yet, the deportation does not exactly correspond to the real Grand Dérangement, for although Acadian families were transported to France, they were not captured in Louisiana. The reenactment of the dispersal is accompanied by the reiteration of the lobsters’ tragic fate ‘Tit Edvard learned from Hermance in the second tale: the little crawfish uses every opportunity to tell his ancestor’s story. Furthermore, the tales explore the French origins of the Acadians. 1632 functions as a key date, for in that year the lobsters are said to have disappeared from France. In reality, 1632 refers to the departure of the first colonists to Canada.

What unites the three tales is the entangled histories of Louisiana, Canada, and France. A journey back in time and to the origins of the community, the narrated displacements become redemptive moments, moments for the recovery of roots. As literary texts, they “exemplify the fact that memorial dynamics do not just work in a linear or accumulative way. Instead they progress through all sorts of loopings back to cultural products that are not simply media of memory (relay stations and catalysts) but also objects of recall and revision”. Interestingly, the stories still revolve around Cajun culture, with Louisiana acting as an anchor, but the change of settings in the tales and the historical diasporic element add a distinct transnational note.

Transnational Trajectories in Richard’s Tales

Migration not only strengthens the link to the home culture through the memory of landscape, language, and the past. It transforms a culture as foreign elements are incorporated. While Richard’s tales are portrayals of transnational migrations, they also reveal influences from other cultures. Transnationalism, according to Rocío Davis, is a “creative practice” which exemplifies “how cultures circulate through particular products… and become emblems of evolving ways of perceiving the United States and its cultures from within and outside the country”. Considering that Cajun culture is primarily based on oral tradition, there is a lack of original written models Cajun authors could turn to: there has been no Cajun novel in French to this day.

It was only in 1980 that a group of young Cajun authors published the bilingual poetry collection Cris sur le bayou: naissance d’une poésie cadienne. Today, this collection stands for the birth of littérature cadienne. The poems express the authors’ awareness and alarm concerning the demise of French and, by extension, Cajun culture. Still, the collection was not published in Louisiana, but in Montreal, Canada, as were Zachary Richard’s works. The fact that even Richard’s most recent tale of 2010 was not published in Louisiana, but in Montreal, shows how hard it is for the French voice to be heard in Louisiana. Without doubt, the emerging genre of littérature cadienne, despite—or rather because of—the detour via Canada, has become an important motor in the fight for Cajun culture. The establishment of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press (1973) and Éditions Tintamarre at Centenary College (2003-2004), which promote the publication of French works in Louisiana, was another great step towards the dissemination and preservation of French Louisiana literature within the state. The lack of a written tradition notwithstanding Cajun authors have been inspired by French and American literature and have used familiar works as templates. Also, given that Louisiana presents a rich transcultural reservoir of various folktale traditions such as animal tales, magical tales, or supernatural tales), it is not surprising that Richard’s tales display a certain affinity for the folktale. An innovative literary mixture, the tales disclose a transnational Cajun voice.

This is nowhere more evident than in the use of intertextual references. Borrowings from European literary traditions, from African or Native American mythologies, or allusions to particular historical events, identify the tales as transnational—and transcultural—tales. The animal characters, who speak and think like humans, inevitably recall the canonical fables by Aesop (sixth century B.C.) or Jean de la Fontaine (seventeenth century). Although not immediately related to “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” the character of the cicada in the first tale is a distant echo of that fable. The almost blind and slightly hard-of-hearing cicada whom the companions meet, shrugs them off with an impolite and indifferent: “I can’t help you, even if I could, I don’t want to.… Leave me alone. Get you gone!”. His tendency to trade, as we know from the fable, shines through when Télesphore offers his eyes in return for showing them the way out of the oak forest.

A cathingaster cicada

A cathingaster cicada

Other elements recall the philosophical tale. “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly” is one of Télesphore’s profound observations about life and human nature. Strikingly, his statement resembles the fox’s words in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Petit Prince which have become familiar all over the world. Conte cajun resembles this latter tale in many ways, which also conveys a philosophical message, has speaking animals, and fantastic elements. With ‘Tit Edvard sitting high up on Télesphore’s back during the whole journey, ‘Tit Edvard is like the little Prince on his small planet.

Yet, Conte cajun is more than an intertextual mixture of European tales: it includes references to tales of other ethnic origins as well. This hybrid nature is especially visible in the choice of characters as they unite characteristics of African and Native American folktales. Télesphore, for instance, can be considered a universal animal symbol since the turtle figures in mythologies of many other peoples. The turtle plays a fundamental role in Native American mythology, especially in creation myths. The very beginning of Conte cajunresembles such a myth when Télesphore appears from the waters and takes ‘Tit Edvard on his back. Famous in Europe thanks to Aesop’s fable “The Tortoise and the Hare,” the turtle is also reminiscent of Uncle Remus’s tales, of African origin and published by Joel Chandler Harris in 1881, in which Brer Terrapin, the trickster, outwits other animal characters. Interestingly, the spider, an important character in African and Caribbean oral traditions, holds an exceptional position in the tale. For, despite French Louisiana’s obvious cultural connection with the West Indies, the spider, called Anansi, is unknown among Cajun folktales.

Finally, Richard interweaves his narrative with events and references from other nations and cultures, which, at first glance, cannot be directly associated with Cajun culture. It is especially his third tale which reveals such transnational allusions, for instance to the French context: after their escape, the group of crawfish and the rooster live in the “maquis,” a term which, in World War II, referred to a remote place where the résistants to the German occupation gathered (“Maquis”). Like the maquisards, the animals hide in the woods, traveling only during the night and avoiding farms. When they are caught by a wildlife patrol and brought to a refugee camp, the password one of the guards utters to enter the camp is “Jean Moulin.” Jean Moulin, a French politician during the first half of the twentieth century, entered the French national memory because of his activities as the chief of the Conseil national de la Résistance .

It is not without reason that Richard refers to World War II: it was then that the American army realized the crucial asset of the Cajuns’ linguistic abilities. In the last decades, scholars have shown a growing interest in the role of Cajun GIs in World War II. They served in France, Belgium, North Africa, and Southeast Asia; others joined the resistance movement against Germany. As Cajun historian Carl Brasseaux observes: “Cajun translators were as important to the American war effort as the much-acclaimed Native American Code Talkers” (Brasseaux qtd. in Engelbrecht). Similarly, Télesphore’s abilities as interpreter—he knows both the animal and human languages—are crucial to the tale’s positive outcome, and identify him as the tales’ code talker. Thus, Richard highlights bilingualism as the Cajuns’ consequential resource and as important identity marker.

Other allusions situate the tales in a postcolonial context. The very promising “A suivre...” at the end of the third tale indicates that this is not ‘Tit Edvard’s and Télésphore’s last adventure. The crawfish and the two friends pine for their home in Louisiana, but the return trip via ship in winter would prove too hazardous. It is Jacques Cocorichaud who presents them with a solution: the ringdoves are getting ready for their migration to Africa and they are willing to take the company with them. Will there be a forth tale set in Africa, exploring the African influence in Cajun culture? In any case, the African trajectory already exists subliminally in the trilogy, but the postcolonial context is most apparent in the last tale. Indeed, ‘Tit Edward’s and Télesphore’s wanderings from America to Europe, and for that matter the Cajuns’ wanderings between Europe and America, are portrayals of, to use Paul Gilroy’s term, transatlantic routes. More specifically, the crawfish company’s passage to France on the ship does not only revisit the Acadian deportation: the scene of the animals jammed in the bilge of the ship is reminiscent of the middle passage of the slave trade:

On the bottom of the metal cage, they [the crawfish] are on top of each other. As to Télesphore, he is stuck, his shell immobilized because the ceiling of the cage is so low. The silence is incommensurable. Only the breathing sound of the crawfish is to be heard. This little, almost inaudible noise amplifies until it becomes immense, the sound echoes from the metallic walls of the cage and finally transforms itself into an enormous cacophony like the fracas of a stone avalanche.

Additionally, the cruel treatment, the heat, and the lack of fresh air contribute to the parallel. Regarding the Acadians and the African slaves, the circumstances of the capture, the transitional state during the passage, as well as their subsequent mistreatment suggest a comparison. In the tale, then, there is two-way traffic between the past—the Grand Dérangement and the middle passage—and the present—the capture of Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard. Furthermore, when the company of crawfish escapes prison in La Rochelle and takes to the woods, they start to live a “vie marron”. Marron, Maroon in English, comes from cimarròn, a Spanish expression for “feral animal,” a domestic animal which has returned to the wild. By extension, it was used to refer to fugitive slaves during the colonial period in the American South. Today, the French expression means “to live like a vagabond” . As a matter of fact, Richard aligns himself with postcolonial writers such as Aimé Césaire. During his years of militancy in the 1970s, he and other young Cajuns advocated what was calledCadienitude, in the style of Césaire’s term négritude.

On the one hand,Cadienitude stood for the preservation of the history, language, and culture of the Cajuns and the sharing of the heritage of the Acadian diaspora. On the other hand, it was a protest against the stereotyping and discrimination the Cajuns had been subjected to since the end of the Civil War. The concept aimed at rehabilitating the Cajuns’ self-image and advocated the self-affirmation of the Cajuns in order to develop a Cajun identity. The postcolonial background serves, then, to assert Cajun identity with its francophone heritage in the midst of a dominant Anglo-American society. Considering the third tale’s ending, one thing seems certain: the Cajun-Acadian-French connection will be complemented by the African connection, offering an even more comprehensive picture of Cajun culture. ‘Tit Edvard and Télesphore will discover a new country with francophone cultures and continue to spread their knowledge about Cajun culture in their function as cultural ambassadors.

Conclusion

It has been stated that

[t]he most consistent element in Cajun County may well be an uncanny ability to swim in the mainstream. The Cajuns seem to have an innate understanding that culture is an ongoing process, and appear willing constantly to reinvent and renegotiate their cultural affairs on their own terms.

This malleability of Cajun culture is clearly visible in Richard’s three tales. Each tale reinvents the expulsion story and re-enacts the Grand Dérangement, and the multiple migrations and transgressions of national boundaries show the circular dynamics of both literature and memory. Considering the characters’ own displacements and the references to, or mise en abîme of, an event which bears a striking resemblance to the Grand Dérangement, there is no doubt that the tales allegorize the Acadians’ expulsion and that they are a good example of “palimpsestic itineraries of migration”. With Télesphore and ‘Tit Edvard, the reader travels both to different places—from Louisiana, to Canada, to France—and also back in time—from the contemporary setting to the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries. In reenacting the past, Richard’s three tales portray a geo-cultural space where the cultures of the Cajuns, the French-Canadians, and the French meet and display “regional writing’s strategy of protecting local identities by preserving them in literature”. In this imaginary Acadian triangle of Acadiana-Acadia-France, the Acadian diaspora is reunited. Considering that “[r]egions are not so much places themselves but ways of describing relationships among places”, the concept of “migrating literature,” as explored in Zachary Richard’s three tales, highlights the contemporary interplay of the regional and transnational.

It becomes clear that Richard’s notion of Francophonie is more than just the preservation of the French language and francophone culture. Richard propounds a universal, humanist ideology, allowing for solving today’s social problems. This transnational humanism is also present in his Cajun tales and was most recently officially acknowledged by the Cercle Senghor Richelieu which awarded Richard the annual Prix du Cercle Senghor Richelieu de Paris in March 2014 (“Le Prix du Cercle”). The tales express the necessity of turning towards the wider francophone world for the preservation of Cajun culture, as the links established with Canada and France show. Even if the connection to the local is never lost, the transnational becomes more apparent with each tale.

As the tales progress, there is a certain realignment, a shift away from southwest Louisiana to other places which turn out to be important because of their historical and cultural connections to Cajun culture. In reinventing the tragedy of the Acadians from a Cajun perspective and including the lobster-turned-crawfish legend, Richard participates in the dissemination and preservation of the Acadian memory, and thus in the endurance of imaginary Acadia. In crossing multiple boundaries, Zachary Richard not only strengthens the link between the two Acadias, l’Acadie du nord and l’Acadie du sud, and France; he also creates a francophone Cajun prose narrative: the echo of the tales, coming from the allegedly silent voice of francophone Cajun Country, bounces off Canada back to Louisiana. In Richard’s eyes, dislocation and foreign influences are not purely unfavorable; they also entail a gain of other cultural traditions. Indeed, Cajun culture can only benefit from preserving its transnational outlook.

This article was originally published in the European Journal of American Studies under a CC-BY licence. You can read the original, with footnotes and references, at the EJAS website.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews