What happens when people are seen as things?

In Donald Trump’s 2005 hot mic conversation with entertainment reporter Billy Bush, he confessed to kissing women and grabbing their genitals without their consent.

What happens when people are seen as things?

In Donald Trump’s 2005 hot mic conversation with entertainment reporter Billy Bush, he confessed to kissing women and grabbing their genitals without their consent.

I’ve previously noted how Trump, on the campaign trail, will often use the rhetorical strategy of reification (which comes from the Latin word for thing, res, and in this context means “to thingify”) as a way to trivialize the humanity, dignity, needs or opinions of those with whom he disagrees.

As the tape shows, he clearly talks this way in private, too. In a campaign that has epitomized the danger of this rhetoric, women are merely the latest to fall victim to this sort of “thingification.”

Silencing opponents

The history of American political discourse is riddled with the “thingification” of people. We have traditionally treated women, workers, immigrants and people with disabilities as less than human, as objects rather than as people. Doing so enables those with power and privilege to retain their status, since there’s the general understanding that people should be privileged over objects.

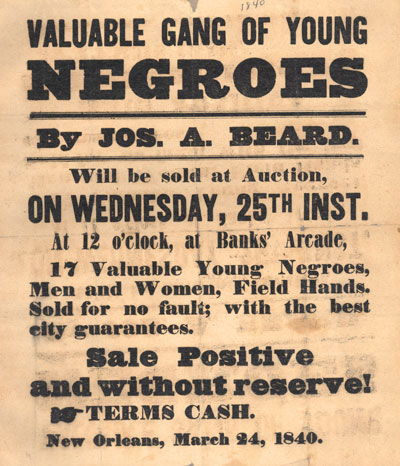

In other words, who counts as people has always been political, so this sort of rhetoric is nothing new. Consider how Americans treated slaves as objects – as property to be bought and sold – rather than as human beings. Slaveholders wouldn’t have been able to own people if we had recognized that slaves were, in fact, people, rather than things.

We even see the “thingification” of enemies in Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address. Much like our current election, the election of 1800 was nasty. In the speech, Jefferson attempted to unify the nation, but he also sought to render his critics as objects, as “monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated, where reason is left free to combat it.”

In other words, he hoped to cast his Federalist enemies as silent monuments, relegated to history.

Jefferson’s belief in Enlightenment rationality meant that he thought even those who held differing opinions from him ought to be tolerated.

Nonetheless, a silent monument can neither criticize nor consent.

Defending the indefensible

Fast forward 200 years, and we don’t have a founding father attempting to unite a bitterly divided nation but Donald Trump being recorded bragging about his power over women.

“I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait,” Trump sneered on the tape. “And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” Trump then looked out of the bus window at actress Arianne Zucker and said, “Oh, it looks good.”

“It,” of course, is a thing, not a person. A thing that he might kiss or grab, even without its consent. A thing can’t give its consent, after all. The comments on the tape suggest that he might, at times, not wait for any at all.

When Anderson Cooper asked Trump about the comments about women at the second presidential debate, Trump’s ensuing apologia – a speech of self-defense – was riddled with rhetorical devices meant to minimize the seriousness of his “thingifying” women.

He responded that he had “great respect for women. Nobody has more respect for women than I do… But I have tremendous respect for women… And women have respect for me.”

If you look at Trump’s words, it’s clear he hoped he could persuade the audience merely by repeating positive terms about women. Meanwhile, the core argument of his defense was simple: Present his remarks as innocuous. To do so he used a combination of denial (“I didn’t say that [I sexually assaulted women] at all”); bolstering, a strategy speakers use to associate themselves with something or someone that the audience views positively (“I respect women and women respect me”); differentiation, which speakers use to reframe what the audience already understands (It was just “locker room talk”); and transcendence, or arguing that the issue isn’t really that big of a deal (We need to “get on to much more important things and much bigger things”).

When everyone’s a ‘thing,’ who’s left?

From a rhetorical standpoint, Trump’s self-defense was a textbook example of apologia, but it wasn’t convincing.

His denial that he had admitted to sexually assaulting women would ring false to people who had heard him on the tape, the repetition of his respect for women is disproved by his own words on the tape, while the attempt to reframe his reification as “locker room talk” has been rejected by folks who actually talk in locker rooms. Meanwhile, his attempt to minimize what he said about women and refocus the nation’s attention on his campaign seems only to reaffirm that he views women as trivial.

He could have perhaps been more convincing if he hadn’t resorted to reification in so many other contexts. As Hillary Clinton pointed out in the second presidential debate, “…it’s not only women, and it’s not only this video … he has also targeted immigrants, African-Americans, Latinos, people with disabilities, POWs, Muslims and so many others.”

The lens of reification can help us to understand what happened between the Gold Star Khan family and Trump at the Democratic National Convention in July. Khizr and Ghazala Khan appeared at the DNC and declared that “Donald Trump consistently smears the character of Muslims.” They asked Trump to stop treating them as objects and to recognize them as people – specifically as Muslims and as American patriots. He refused, instead characterizing them as irrational aggressors.

“I was viciously attacked by Mr. Khan at the Democratic Convention,” he tweeted. “Am I not allowed to respond? Hillary voted for the Iraq war, not me!” To Trump, Khan’s speech at the DNC was a vicious attack. Khan, therefore, could not be a loyal and patriotic American Muslim, as he claimed, but rather – as Trump has argued – all Muslims are aggressors.

The problem for Trump’s targets and opponents, of course, is that the rhetoric of reification allows Trump to deny legitimate criticism. Because objects can neither consent nor criticize, the use of reification can be seen as an expression of power.

“I am running against the Washington insiders, just like I did in the Republican Primaries,” he tweeted during the summer. “These are the people that have made U.S. a mess!”

Washington insiders are people “that” have made the nation a mess, not “who.”

Even as Trump acknowledges his enemies’ personhood, he also negates it. Trump is a person and his enemies are objects. Just as the “thingification” of women denies them the power to consent to what happens to their bodies, when Trump “thingifies” his critics he denies them the ability to speak and rebut his accusations.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews