1 Understanding children’s mental health

In a similar way to our physical health, our mental health can go through sub-optimal periods and will not be as good as we would like. We can go through periods of time when we seem to get ‘every cold going’, stomach bugs or simply feel ‘off colour’. In a similar way, our mental health can be good, not so good or downright bad.

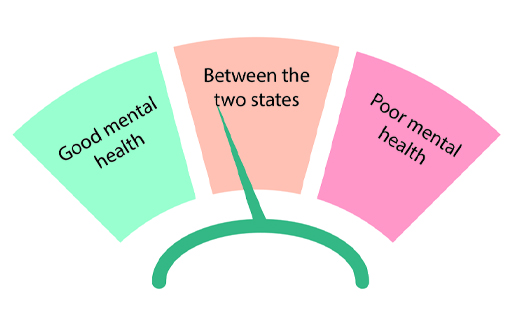

It may be helpful to think of mental health as being like a windscreen wiper: on one side mental health can be good, but it can move across to the opposite side where it is bad. There is a great deal that we can do to keep our mental health on the good side of the spectrum.

Figure 2 represents mental health as a spectrum, with good mental health on one end and poor on the other. In a similar way to a windscreen wiper, mental health is not static and it can move from one end of the spectrum to the other.

In a similar way, there can be variability in children’s mental health, meaning that it can vary between being ‘good’ (or ideal) or ‘bad’ (or compromised). However, there are significant differences between adults and children. For instance, very young children are likely to have less understanding about their feelings: they can find it difficult to clearly identify their emotions and they will not have the same vocabulary to describe their emotional state using words. For example, a young child’s anxiety may manifest in physical form, whereby they have a ‘funny feeling in their tummy’ about a situation they are in (or anticipate they will soon be in). An adult is more likely to recognise the physical sensation they are experiencing (e.g. ‘butterflies in your stomach’) as a feature of an anxious state.

However, for a young child in an anxiety-inducing situation, it may be a challenge to understand the feelings they are experiencing, and to regulate their emotions so that they do not become overly distressed. For instance, for a very young child, the thought of being separated from a loved adult can cause ‘a funny tummy feeling’. Also, it is likely that very young children will not have the vocabulary and language development to be able to articulate their thoughts and feelings. Very young children, in particular around the age of two, are likely to demonstrate their emotions, including anxiety, by displays of high emotion including crying, shouting and kicking; in other words, by having a tantrum straight after being separated from a loved one (also known as an attachment figure). These responses are not usually seen as majorly concerning for very young children, but the same sort of response in older children is usually a sign that could mean issues in terms of their mental health. If a child is frequently experiencing situations that cause anxiety which seems disproportionate to the event (e.g. a Year 5 student having a ‘tantrum’ every time they are dropped off at school), this is usually a sign that a ‘problem is a problem’ which is impacting on their general wellbeing. This older child is more likely to have compromised mental health and be at risk of developing a mental health condition which will require a professional assessment. Therefore, understanding children’s behaviour for their age and stage of development is extremely important for all adults involved in the care and education of young children.