1.2 A short history of digital humanities

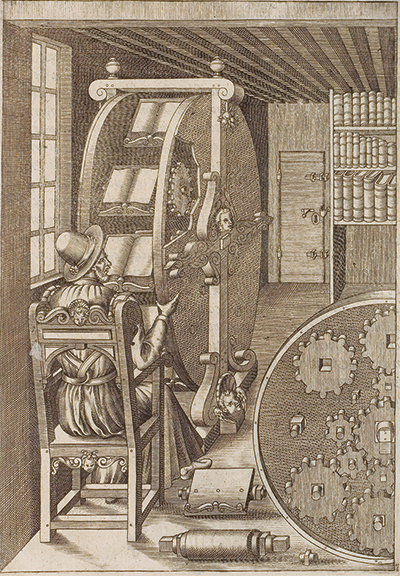

The arrival of digital media is not the first time that the Humanities have faced a fundamental change of medium. The rise of print in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries led to profound transformations in scholarly work, for example by lowering the price of books and increasing the speed of their production, making it easier to assemble personal libraries and to communicate with a wider public. It also led to anxieties about how to manage the increasing amount of books, resulting in ingenious solutions, such as Agostino Ramelli’s ‘book wheel’, a rotating bookshelf and desk.

The arrival of a new medium, however, did not mean that previous ones were abandoned. Humanities research methods are still developed for the analysis of both print and manuscript sources. The increasing availability of computers opened new research methods and questions from the middle of the twentieth century.

In his visionary study ‘As We May Think’, Vannevar Bush theorised in 1945 about a ‘memex’, ‘a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanised so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility’. Superficially, the memex may resemble Ramelli’s book wheel, but for Bush the memex had the potential to become ‘an enlarged intimate supplement to [the user’s] memory’ which would allow users to build ‘trails’, permanently joining items into patterns of their own choosing (Bush, 1945, p. 6).

Father Roberto Busa worked in 1949 with IBM on the creation of the Index Thomisticus, a concordance of all the words present in the works of the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas. The method of concordancing (taking a given word and finding its context) was well established in the Humanities before the advent of computers, dating back to medieval times. Computers enabled the deployment of this technique on a larger scale, including the 11 million words written by Aquinas. Other scholars also began to employ computers to count and measure information, giving rise to the first studies in ‘humanities computing’.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw the rise of a further digital technology, the internet, enabling computers to connect across the globe and transmit information at high speeds and low costs. Scholars were quick to realise its potential and the 1990s saw the rise of several prominent projects which took library and archives holdings and made them digitally accessible, a process known as digitisation (as you will learn in Session 2).

The rise of the internet also provided scholars with new objects of study that had no material equivalent, the so-called ‘born-digital data’ (see Session 4). From the early 2000s, scholars engaged in the processes of creating and studying digital texts, images and sounds began to define their work as ‘digital humanities’. In the last decade, scholars have come to argue that the digital humanities form an integral part of Humanities research, ‘widening the scope of the humanities, opening access to sources, and broadening definitions of scholarly activity’ (Thomas, 2016, p. 524). In the rest of this course, you will discover how these new opportunities can develop.

Activity 2 What can you do with digital documents?

What tasks do digital documents (texts, images, sounds, etc.) allow you to do more easily or quickly than print or manuscript?

Write down why you think the following properties of digital resources can be useful to a researcher.

Discussion

Digital documents can be read by either printing them out on paper or on screens. They are portable and usable on a variety of devices.

Discussion

Digital documents can be copied an infinite amount of times without damaging the original and without loss of quality to the copies. By contrast, copying material documents is either damaging to the original or produces lower-quality copies, or both.

Discussion

Digital documents can be searched quickly through online catalogues and archives. But the abundance of certain types of digital documents requires careful search strategies and metadata.

Discussion

Digital documents can be stored on your computer or mobile device (if copyright permits; see section 6) and organised into portable collections. Researchers can work even when they are far away from a library.

Discussion

Digital documents can be examined through a variety of approaches, from counting word frequencies to visualising networks.

Discussion

Digital documents can be analysed on both small and large scales, from in-depth analysis of a few texts or images to the study of millions of words or images.

Discussion

Digital documents and your analyses of them can be shared easily with other researchers (if copyright permits) through digital platforms.

(Activity adapted from Spiro, 2008)