Implementing CBT in practice

The implementation of CBT in practice involves three key stages: assessment; intervention and evaluation (Zandt and Barrett, 2017).

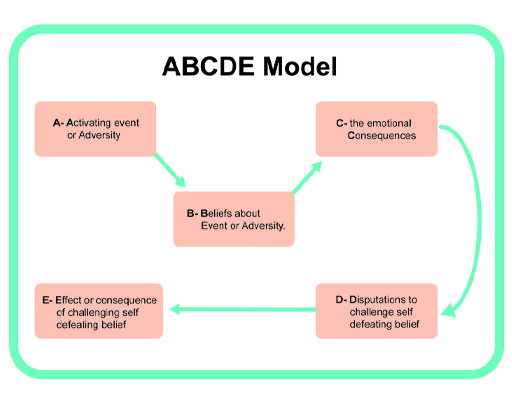

The ABC model is often used at the initial assessment stage as a means to make sense of the presenting issues.

- A being the activating event (i.e. what seems to trigger the behaviours/responses)

- B being the individual’s belief system or attitude in relation to the event

- C being the consequences as reflected in behavioural or emotional reactions.

The key idea behind CBT is that when faced with any external event we can change our thoughts, feelings and behaviours, although this is not always easy to do, and that is why so many people have benefited from CBT as a form of therapy. As a result, we can challenge how we perceive events and look at alternative and potentially more helpful ways to view our experiences.

As part of intervention, steps D and E are included (as shown in Figure 3):

- D being the challenges/questions around the more negative, self-defeating belief

- E being the effect of challenging previous attitudes and beliefs.

To help illustrate how CBT can be applied in practice, you will first be asked to think about a case study of an adult before thinking about psychotherapy with children. Any new ways of dealing with the problem that have been put into place and practised are evaluated to see how effective they have been. For example, this will include whether there have been changes in any interactions, how the person is now feeling and how they currently see themselves.

Activity _unit8.2.1 Activity 1 The ABCDE model in practice in adults

Sam has been having problems at work over a number of months (Activating event) and things feel like they are getting worse. As a result he is feeling very low, tired and irritable (Physical and Emotional Consequences). As a result he has been avoiding people, especially his usually supportive family (Behavioural Consequences) who tend to be ‘stiff upper lip’ sorts. He comes home one day, after a tough day at work, when he is feeling especially low and tries to talk to his wife, Amy, about what has been going on for him.

Amy seems preoccupied and Sam gets angry (Emotional Consequence). He thinks ‘No one ever cares about me or has time for me’ (‘All or nothing’ self-defeating/negative Belief).

How do you think Sam might start to challenge his negative thinking (step D)? What questions could he start to ask himself?

How might any of the responses to his questions help him to change his initial thinking (Step E)?

Discussion

You might have thought of some of the following in relation to questions and the ABCDE model:

- When did the issues at work begin? Was there a particular trigger or event?

- What appears to make things better or worse? Has Sam noticed improvements in his mood on, say, a Friday night (i.e. leaving work for the weekend)?

- Carefully consider the evidence. Who are the people that Sam cares about? How likely is it that none of these people care about him?

- How does he know that Amy was ‘preoccupied’, and how has their relationship been more generally since he has been avoiding family members?

- Who has he tried talking to about his problems so far and how does he usually go about communicating his feelings to others?

- Why might Amy be preoccupied and what has helped him and Amy to communicate about important matters in the past?

If we delve more deeply into our own negative thinking and the automatic responses and conclusions we can reach, we are more likely to find alternative ways to solve our problems. We can gently interrogate ourselves to see if our original thinking holds true.

CBT techniques can work in a similar way with older children and adolescents, using worksheets or other resources to help them to make sense of the problems they are encountering. They can talk and draw diagrams to help explain what is happening for them in different contexts and begin to understand more about how and why they react to certain triggers. They can then learn to find alternative ways to think about their problems and create their own solutions with the adult guiding them along the way.

However, how is such a focus on the way feelings, thoughts and behaviours are linked together possible with young children, who are perhaps not able to express their thoughts or feelings verbally?

In adaptations of CBT for use with children, play is used in various activities to help explain some of the issues in a simpler and more meaningful way. For example, through an activity such as using a pair of coloured glasses to look at different objects, a child can begin to understand how we might ‘distort’ things ourselves when we experience certain situations.