1 Reading aloud

Reading aloud to children from their earliest years matters. Inviting their playful engagement and attention though the use of actions, sounds, words, chants and props, and participating in connected book chat helps to enrich their narrative understanding and pleasure. In later years, retaining time in school for reading aloud remains crucial to nurturing the habit of free reading. However, while it is often recognised in policy and practice, and teachers value this time with their class, the pressure of curriculum coverage tends to reduce opportunities to engage in this shared reading experience (Merga and Ledger, 2018).

Some studies into reading aloud focus on its value for developing literacy skills by tracking gains in vocabulary, comprehension and decontextualised language. For example, Zucker et al. (2013) show that reading aloud with ‘extratextual talk’ is associated with vocabulary gains in early years. Other studies identify that children must not only hear, but be prompted to use the new words in order to sustain long term gains (Wasik and Hindman, 2014). The latter study highlights the value of teachers using contextualized text talk (in the book) and decontextualised text talk (beyond the book), as part of read-alouds. Although in many cases the claimed benefits are modest (Hall and Williams, 2010), the work of Kalb and van Ours (2014) in Australia does indicate that reading aloud recurrently to 4-5-year-olds enhances their reading, mathematics and cognitive skills at age 8-9.

Other studies undertaken in classrooms tend to examine reading aloud as it happens and focus on affective and behavioural consequences, such as developing a sense of belonging. This, Wiseman (2011) observes, can be particularly valuable for children from marginalised groups, such as those speaking English as a second language and struggling readers. Read alouds are often pitched at a level above what most children could access alone. Whilst cognitively challenging, hearing engaging texts places few literacy demands upon children, which enables them to experience increased autonomy and fluency, and focus on comprehension (Kuhn et al., 2010).

Watch the following video of Ellie, a teacher at Elmshurst Primary School, London reading to 9-10-year-olds in her class.

Transcript: Video 1

[TEXT ON SCREEN: Reading aloud brings the narrative to life]

[TEXT ON SCREEN: Reading aloud helps children to make connections]

[TEXT ON SCREEN: Reading aloud prompts discussion and interaction]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[TEXT ON SCREEN: Reading aloud encourages deeper engagement]

[TEXT ON SCREEN: Reading aloud is a shared, social experience]

Activity _unit6.1.1 Activity 1 Considering the value of reading aloud

Take a moment to think about why educators read aloud to young people.

Drawing on your experience of reading aloud to children, make a bulleted list of as many different kinds of knowledge, skills, understanding and attitudes that you think may be fostered by regularly reading aloud to 3-11-year-olds.

Comment

Reading aloud to children is valued and valuable. When effective it helps to develop children’s:

- vocabulary

- curiosity and desire

- knowledge and understanding of the world

- capacity to process challenging content beyond their reading ability

- capacity to respond to texts informally

- listening skills, concentration and attention span

- internal models of fluent reading, based on this externalised model

- openness to the music and drama of language

- narrative knowledge (e.g. how stories begin and end, plot, characters)

- reading repertoires

- reading miles (i.e. the amount of reading)

- reading for pleasure

- sense of belonging to a community.

There are many benefits of hearing stories and other texts read aloud regularly. Listening to rich engaging texts offers a foundation for later understanding and helps sustain a love of reading throughout education. It enriches children’s inner treasure chests of words (Sullivan and Brown, 2015): in fact, the word ‘vocabulary’ in German ‘wortschatz’, literally means ‘word treasure’.

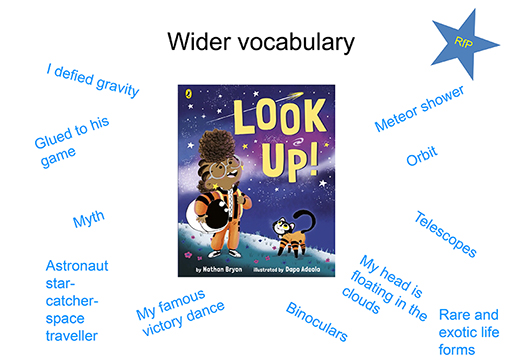

Look at Figure 2, which shows the range of language used in Look Up! by Nathan Byron and Dapo Adeola. Brilliant books are packed with new vocabulary, so hearing and reading such books can enhance children’s prior knowledge and understanding, and enrich their capacity to access the curriculum.

As well as fiction, non-fiction texts also introduce children to subject-specific higher-level vocabulary, which they are unlikely to come across in everyday life (Beck, 2002). Teachers who read aloud to inspire and motivate choice-led independent reading are also introducing the young to the grammar of written language and building something known as ‘books in common’, which you will learn about in the next section.