4 Supporting multiliterate children’s reading at home

Approximately one fifth of children in British primary schools are described as being speakers of English as an additional language, and so when considering children’s Reading for Pleasure at home, it is important to consider those children who are bilingual/multilingual (speakers of two or more languages) and biliterate/multiliterate (readers and writers in two or more languages ).

However, these children are far from a homogenous group and there is no one-size-fits-all approach to understanding or supporting multilingual children as readers. Much of the research on multiliteracy focuses on newly arrived immigrants and those children in the very early stages of learning English, yet there is some evidence to show that by upper primary years, many multiliterate children in the UK have switched to reading predominantly in the language of the school (Worthy, Nuñez and Espinoza, 2016). One element of promoting children’s multiliteracy is to foster and enable Reading for Pleasure in their heritage language.

Research carried out by Little (2021) took an in-depth look at the reading lives of seven children aged 8–13, across six multilingual families in England over nearly a year. This study illustrated that children expressed very different perceptions of and preferences for reading in English or in their heritage language. Little (2021) explains that most of the children ‘mentioned at least some frustration, at some point, in their multilingual reading journey’ (p.11). However, children with personal migration histories showed strong emotional connections to heritage language books, particularly those books that had journeyed with them. Two of the children explained that they might choose to read a book in heritage language if they had firstly read and enjoyed it in English.

Many multilingual children, however, experience issues of access to heritage language reading materials and the role of supporting multiliteracy and facilitating Reading for Pleasure in heritage language tends to fall to parents.

Whilst it may not be possible to offer an extensive collection of books and reading materials in every child’s heritage language, there are ways in which schools can support multiliterate children. Working in partnership with parents and the local community can help to build a bank of resources, and companies such as Mantra Lingua and Letterbox Library offer a collection of dual language books and eBooks. Most importantly, by using and adapting strategies to find out about children’s home reading practices (see Session 4), you can celebrate children’s multilingual reading and community languages and support multiliterate children’s reader identities.

Box _unit8.4.1 Optional resource

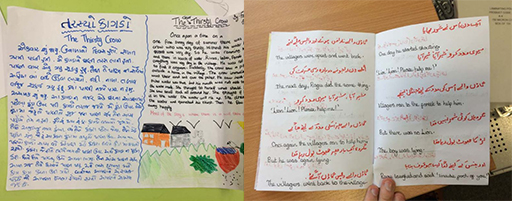

In this example of practice [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , Jonny Walker, Assistant Headteacher at Park Primary school in East London, describes how children, staff, parents and the local community co-created a shared library of homemade bilingual books of stories that the children’s older relatives had passed down in their first language. The enthusiasm and enjoyment that the project engendered among children and their families was inspiring.