3.4 Secular II: Icons in the market

It should be clear by now that icons are the most important religious aid for Orthodox Christians. The possession of icons, however, was/is not only the privilege of the Orthodox faithful. There is strong evidence that icons were in demand in Catholic Europe.

Following the Fall of Constantinople in 1204 to the troops of the Fourth Crusade (see Appendix 1 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ), the Byzantine Empire was fractured. A number of former Byzantine territories came under Latin rule, where Greek Orthodox and western Roman Catholic faithful were forced into coexistence. In some places this lasted for a short period, in others for much longer. One of the best examples of such prolonged and prolific symbiosis is the island of Crete, where Venetians ruled between 1211 and 1669. The stable and prolonged rule of the Serenissima (as Venice is traditionally known) led to the establishment of a hybrid society, perfectly reflected in the creation of the Cretan hybrid icon. Cretan icons became popular in the years following the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottomans.

Following the capture of the Empire’s capital, a number of Greeks fled the city and relocated in Italy. The peninsula witnessed an influx of icons, which is not surprising as the Orthodox brought with them beloved and sacred objects (Lymberopoulou, 2007b). It is not a coincidence that icon collecting is evident from the fifteenth century.

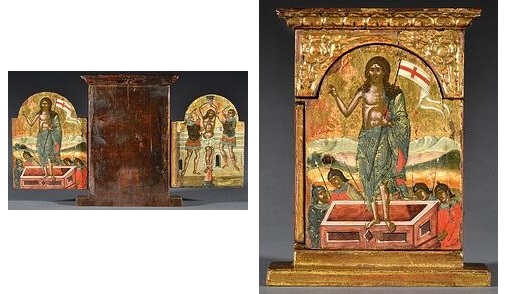

The Cretan hybrid icons in particular combine characteristics of both Byzantine and western art, which accounts for their popularity among both Orthodox and Catholic. An illustrative example is offered by the portable triptych depicted in Figure 8: while the triptych is painted in the Byzantine style, three out of its five scenes are drawn from western iconography. The Crucifixion and the Carrying of the Cross can be found both in Byzantine and western art; however, the iconography of the Pieta (especially in the white headscarf underneath the Virgin’s chin), the Flagellation (rarely depicted in Byzantine art) and the Resurrection (with Christ emerging from his tomb) are popular in western art.