3 Telling our stories to others

Inevitably there will be moments where you want to introduce your inquiry to others. This may be as part of a reporting process during our inquiries, as a way of bringing others into our inquiry practices or to share the project as part of a ‘completion’ process (although, as we have argued, an appreciative stance to inquiry is difficult to contain within a specific timeframe as inevitably inquiries will continue through our practices and thinking). When we want to share our stories of inquiry, we are inevitably starting from a potentially very different place from those who may be reading or listening to us. So, our abilities to tell a compelling, exciting and inviting story to others about the ongoing potential of our inquiries is vital.

Throughout this course, we have shown how the processes of immersing, imagining and innovating brings different images, metaphors and languages into our thinking and practices (Scott and Armstrong, 2019). These vocabularies in themselves create new ways of expressing the issue, new ways of describing it, and new language to help others engage with it in a way that pushes them ‘beyond the orthodox imagining’ (Dey and Mason, 2018, p. 89).

These different images, metaphors and languages form a new way of storying our inquiry to help others envision the future with us. As Zandee (2013) argues, using these new languages in ‘stor[ies] and other forms of poetic language can [be] insightful, create connection, and open our imaginative eye’ (p. 76), whereby we can help others think about future practices in a different way. Composing a written expression of the story of our inquiry (which in other situations is often presented as a report) acts as a vehicle to coalesce others around. In doing so, we can invite others to share in the story and and become partners with us in ensuring that actions and decisions work towards the identified future (Watkins, Mohr and Keely, 2011).

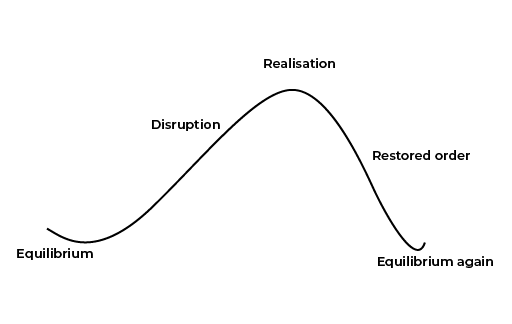

Session 2 introduced you to Todorov’s narrative arc (1969) as a way of structuring how you think about the stories you were collecting and writing. This next activity revisits that arc as a way of structuring a story about inquiry.

As a reminder, there are five stages of the narrative:

- Equilibrium exists at the start of the story.

- Disruption occurs when an action or a character disrupts the equilibrium.

- Realisation occurs when the characters acknowledge the problem and undertake a quest to solve it. The narrative builds to a climax.

- Restored order develops as the damage is gradually repaired.

- Equilibrium again occurs when the problem is fully solved and some form of (new) reality is possible.

Activity 6 Emerging stories of the future

Spend time individually or collectively thinking about the story of your inquiry using this arc as a basis. You may find that there are multiple points you want to make under the heading ‘disruption’, or multiple ways in which ‘restored order’ happened. You may also begin to question whether the final title, ‘equilibrium again’, is suitable for your story, or whether you feel that, as a result of restoring order, you have set in motion a new disequilibrium.

Begin to write your story, considering:

- Where do you need to start from to bring others with you who may not have been as involved in the processes of inquiry?

- Who or what are the main characters and what role do they play in your story?

- What metaphors, images or questions you can use in your story to help the reader/listener begin to ‘see’ practices or issues differently?

- What form could your story take? What evidence might you use (e.g. stories, quotes, pictures, videos, personal reflections) to create a persuasive case for thinking and doing differently?

- What messages do you want the reader/listener to carry with them from the story into their own practices?

Note: You may feel that a report is not the best format. You might consider a video, a podcast, a blog, a cartoon strip or a poem. But, we don’t always have the luxury of deciding our format. If you have a reporting form that you are asked to complete, you may need to either adapt this storying to fit within the prescribed template or find an innovative way to attach it or make small changes to the form to allow you to tell the story as you want. This isn’t always easy. Sometimes we have to work within other people’s boundaries, but, having an engaging, inviting story before completing a template can still create a better account of what has occurred than starting from the boxes on a form.

Comment

As with any writing, and particularly story writing which can be complex and have many layers of characters and different sequences of actions, we as authors can sometimes get too close to the text. It is useful to have someone else read your story, seeing if it makes sense without knowing the details of the project or sequences of action. As well as sense-checking, it may be helpful to ask them what aspects they found interesting and engaging, what they wanted to know more about, and whether anything strikes them as missing from the story.

Having considered how to share our inquiries with others, the next section returns to considering your own inquiring stance.