9 Revisiting adaptive management

The adaptive management approach to doing development has a strong evaluative seam running through it. It is a methodology where ‘trial and error’ is considered the most effective way to achieve desired outcomes and impact. With adaptive management, actions are regarded as experiments and the results of these experiments are used to continually learn about a system in situations where knowledge is incomplete and uncertainty is high. Thus, the adaptive management approach is based on learning by doing (Cundill et al., 2011, p. 14). As such, regular and frequent evaluation is a fundamental component of the approach.

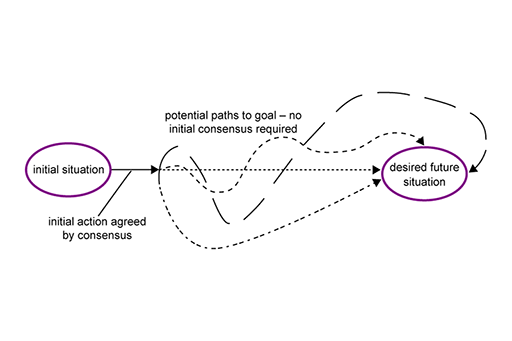

While the goal or objective that is being targeted is clearly defined, the means employed to get there are flexible. The right-hand end of the results chain would be clearly defined, but the left-hand end would deliberately be left a bit unclear as shown in Figure 6 above. As such, it is more a project management approach than an evaluation method but fits focus on ongoing and persistent evaluation is worthy of note here.

A key element of the approach is ongoing monitoring, so that the results of different actions can be tracked and reviewed. Actions found to be unsuccessful can be dropped, successful ones rolled out, and unpredictable events and accidents better negotiated.

Thus, it takes an experimental approach, which allows the cultural, contextual environment of the project to be better understood as it progresses, challenging assumptions in real time, while there is still the opportunity to re-orientate project activities and develop new ones if necessary. This iterative approach allows the project to take better account of prevailing systems and actors. It encourages learning throughout the project as new evidence emerges, challenging development actors’ thinking, avoiding rigidity, and an over-reliance on tools such as the logframe. It also holds out the promise of fewer failed projects.

In terms of the results chain, its very attractiveness of being dynamic is also its major drawback: it is demanding, requiring flexibility, ongoing adaptation, and the embracing of uncertainty. So adaptive management requires a very particular management skill set, which can both work with constant evolution (and occasional revolution). Many current development actors have worked with RBM for decades and would find this more contested and chaotic approach difficult to negotiate. It also requires policy makers and donors to live with greater uncertainty. Most donors demand clear interventions, reports that talk to those same interventions in terms of specific outcomes, not unexpected and surprising ones, and actions that are completed within a particular time frame.