1 Conventional evaluation critiqued

Project planners tend to select planning and implementation approaches favoured by donors rather than those they may feel contribute most to ‘good’ development management. When it comes to evaluation, the same applies.

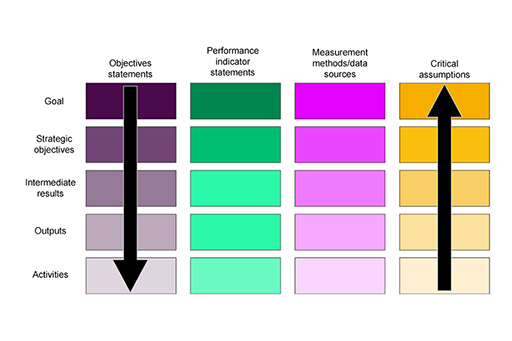

As you saw in Week 2, Results-based management (RBM) is the dominant orthodoxy for development management today. This approach assumes that impacts will be achieved within a given time frame based on an established plan (e.g. a logframe, a template for which is shown in Figure 1 above) with inputs producing outputs that result in outcomes and impacts. The effects of this are:

- the focus is on measurable and objective technical change, rather than shifting power and engaging with the systems and structures that keep poor people poor and maintain inequality

- the focus on achieving targets against a plan may mean that opportunities for achieving change in unexpected ways are missed.

Conventional evaluation approaches miss much of the complexity of development because they fail to take account of:

- the multiple interested parties involved (e.g. public, private, civil society, organisations and individuals)

- the many fields in which development happens (e.g. social, economic, employment, health, education, environment)

- the different levels (e.g. local, national, regional, global)

- the different interests, values, agendas, cultures and power differentials involved

- the dynamic and emergent nature of development, where there is uncertainty, unintended consequences and unevenness in development outcomes and impacts.

Consequently, conventional evaluation can be overly rigid, narrow in its focus and inadvertently blind.

For the following activity, you will reflect on your own experience of carrying out an evaluation.

Activity 1

Take a moment to consider the following questions: (Note: Your experience may be of a project (not necessarily development related), an individual’s performance, a piece of writing or something else.)

- How empirically based was your evaluation, and how much did you feel judgement played a part?

- Do you feel an empirically based evaluation is fairer than one that includes a high degree of judgement, and why?

- What would be necessary to ensure the exercise of judgement was robust and well grounded?

Note your answers in the box below.

Discussion

However empirically robust you may think an evaluation is, there is likely to be an element of judgment. This comes in when you interpret and analyse because data does not speak for itself. Numbers can only ever tell you a partial story.

A further challenge when working with project data is whether there is a causal relationship between the observed change and the intervention. Just because an intervention has been put in place, and appears to be successful, doesn't mean it was the intervention, alone or at all, which caused the change. Moreover, change around values and norms takes far longer to evidence than a one off, snapshot RBM evaluation would show.

In order to make the exercise of judgment robust the reasoning needs to be clear, fully explained and grounded in the data evidence. Such reasoning, however, does not exclude the possibility that someone else might make a different judgment based on the same data. This acknowledges that interpretation and analysis is about making a case which inevitably pivots on judgment.