4 Transforming your capabilities for managing change with STiP

Critical Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice are only two of the multiple traditions of systems thinking. There is not a formula or dogma regarding when to use one tradition or another, but different traditions may be more suitable than others for different situations and tend to encourage certain framings. Generally, a CSLS encourages collaboration to seek systemic improvements to some messy complex situation that multiple stakeholders regard as critically problematic.

CSLS challenges participants to critically examine social structures, power dynamics, and inequalities. Meanwhile, communities of practice are set up by groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. CoPs provide a nurturing environment for collaborative learning and reflective dialogue, with members challenging each other's perspectives, and co-creating new understandings through their interactions.

CSLS and CoPs, like many other learning systems associated with STiP, share an orientation towards collective inquiry. A systems practitioner rarely develops their practice alone, instead building on the ideas of others and working with others. In order to start thinking about how you manage change with others in your situation of concern we can once again use the PFMS framework. This framework was introduced in Week 1 of this course, but your perspective about your own PFMS has (hopefully) been transformed after your engagement with STiP concepts such as Learning Systems, CSLS and CoPs. This re-engagement with the PFMS framework also illustrates iteration as a central principle of STiP.

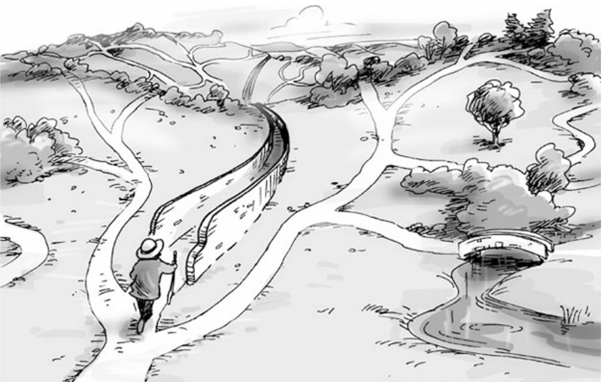

Systemic practice is characterised by iteration – a form of repetition. Iteration involves taking the output of a process and using it as an input for the same process. Applied to learning about practice, this means that you repeat a process of learning on top of the result of prior learning processes, and this deepens your learning. As it deepens it becomes appropriate to add more elements because these now make sense – they have something to adhere to. In practical terms this means going over the same sorts of processes but each time entering the material with the understanding you had achieved in your previous look, and hence seeing it with new eyes.

Activity 3 The people of the PFMS heuristic and its potential for learning

Complete the following grid regarding using your own PFMS with others for some sort of collective activity relating to a shared situation of concern which could be vocational, community or interest based. This may be based on a shared practice or a critical engagement with a situation considered problematic with you and others, even if your inquiry was not formally designed as a CSLS or a CoP.

| Practitioners (P) | Which other practitioners do you work with? | |

| Framework of ideas (F) | What ideas are informing your practice? Do you have a shared set of ideas or are you all working with different ideas? Are there particular ideas you have heard about that you would like to explore further? | |

| Methods (M) | What methods and tools are you using? | |

| Situations of concern (S) | Do you have a shared situation of concern? If so, what is it? |

Comment

As outlined earlier, this course is about managing change with STiP. The question of where change occurs and what constitutes change is a vexed one. This is particularly true if one wants to engage in managing change systemically. Changes can of course occur in any of the elements F, M, S and/or P. But in managing change, when practice is understood as a relational dynamic, you are likely to be most concerned with the changes that you personally engage with because you perceive them to be a part of your system of interest. Changes that occur in us as practitioners, coupled or in a relational dynamic with the material world around us brings into focus how practitioners:

- understand and interact with the material world

- choose which theories or frameworks they use to interpret situations

- become aware of whether their choices are explicit or implicit

- understand situations and employ techniques, methods, tools or methodologies.

Combine all of these elements together in ways that are context sensitive and, where possible, practitioners both learn and change things for the better.

This final section introduces another short iteration around your inquiry process aimed at strengthening your STiP.

As discussed earlier, preparing a systems map encourages moving from the systematic to the systemic. However, creating a systems map may not be sufficient to trigger a shift in thinking from the systematic to the systemic so that you can hold both in creative tension through systems practice.

Firstly, it’s not the tools that you use but how you use them that lead you to systems thinking in practice. A shift to fully-fledged systems thinking in practice would also need careful consideration of where boundaries might most appropriately be placed. You would need to consider each element in relation to others in the context of a system of interest as a whole. In other words systems literacy – your ability to follow the rules of using systems maps – must be underpinned by your systemic sensibility – your capacity to think and act relationally.

Recollect the image of the woman depicted in the animation in Activity 2 in Week 1 of this course, who was interested in the pond as a source of fish. In that particular example an assumption, or articulation, of purpose – to be a source of fish – carries with it the implication that the pond must contain the necessary ingredients, processes, and possibly be supplied with necessary resources, to produce the fish. If it is on the wrong side of a chemical plant, too shaded or too small to contain sufficient variety of life it may not function as she wishes. Therefore her identification of the pond as a ‘system to provide fish’ implies certain necessities that the pond must provide if she is going to receive any fish.

In situations such as this there are no right answers, someone else might see the pond as ‘a system to provide bathing facilities’ for example. The pond perhaps can be both but the choice of purpose is that of someone (a person or group) and it follows that the requirements to maintain each of these systems of interest are not the same, and may clash. Importantly, such clashes may happen inadvertently and people may work at cross-purposes when they have different ideas about what the system is meant to achieve and about the most suitable means for achieving the intended outcomes. Checkland coined his PQR ‘formula’ to make such assumptions explicit and facilitate agreement and reflection on the nature of a system. Checkland’s advice is to formulate a description of a system of interest in the form:

A system to do (what, P), by (hows, Q) because of (why, R), referred to as a PQR statement in the tradition of Soft Systems Methods. (As an interesting aside, this was originally called the ‘XYZ’ formula, but it was quickly renamed as it became clear that this tended to result in confusion because of the similar sounds of ‘Y’ and ‘why’. More background on that can be gleaned from pages 164–5 in Ison (2017).

In Activity 4 you are going to consider what might be in the box, if you were to consider this course as a system. An answer to this activity could be typically drawn as a diagram, with:

- inputs flowing into a set of processes or activities identified as a rough ring – a process boundary which distinguishes the system of interest from the environment of your system, and

- outputs flowing out from the set of processes.

Activity 4 Expressing your understanding of this course as a system of interest

From your own perspective, write down how you now view this course. What transformations would be appropriate? Write your answer in a sentence that starts:

A system to...

In doing this think firstly about what you have gained from the course – this would be the output of the system as a result of a transformation process. Secondly think about what processes or activities need to take place in your system in order to achieve the outputs you have identified. Lastly think about what inputs you need to ‘feed’ or deliver the processes you have identified.

Try to capture your answers to this activity in a diagram.

Discussion

There is no single ‘right’ answer to this activity, because what is in this short course as a system depends on your perceived purpose of it and on the perspective taken. Take a look at the answer below, by one of the module authors in relation to the Open University module. After you’ve completed your diagram, compare and contrast this with your own answer. Note: some of the notes in the diagram are specific to the module, such as ‘engage in forum’ and ‘feedback on TMAs’ and don’t relate specifically to this OpenLearn course.