2 Does income inequality drive or hamper economic growth?

Addressing economic inequality is an important concern for many policy makers, as economic and social inequalities, such as health inequity and gender or racial inequality, oftentimes intersect. For example, health outcomes such as life expectancy or child mortality are worse for people living in less affluent households (Pickett and Wilkinson, 2010). Similarly, in the US, 71.7 percent of White households own their own houses compared to only 41.7 percent of Black households (Hermann, 2023).

Nonetheless, while the correlation between economic inequality and social inequalities is quite well established, the link between economic inequality and economic growth is less clear. Within economics the question of whether or not we need a degree of income inequality to grow our national incomes remains a topic of contestation.

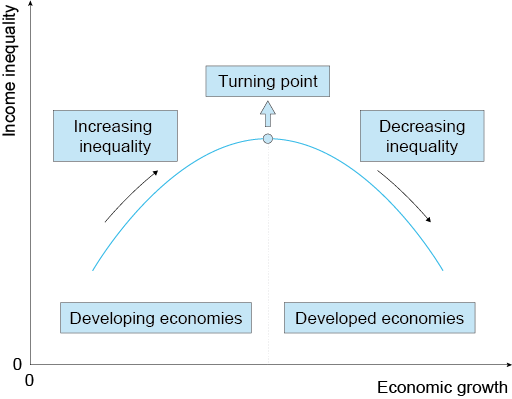

Historically, many economists believed that an unequal distribution of wealth and income was the price to pay for higher economic growth. Most famously, Simon Kuznets, a Belarusian-born US American neoclassical economist suggested that as a country undergoes economic development, income inequality will increase at first and then decrease again over time, as workers could organise themselves and put pressure on policymakers and employers to pay them higher wages (Kuznets, 1955). As illustrated in Figure 3, this relationship between economic growth or development and a country’s income distribution is captured in the Kuznets curve, represented as an inverted U-shape.

Since its appearance, the Kuznets curve has oftentimes been used to push-forward the idea that economies grow when firms do well and have spare capital available in the form of savings that they can re-invest into the production process (Galenson and Leibenstein, 1955). This is because the more profit capitalists make, the more savings they have available to re-invest into the production of goods and services, which in turn will foster innovation and technological advancements.

Proponents of ‘trickle-down economics’ draw on this logic to argue in favour of tax cuts for the wealthy (as this will incentivise them to invest more) and a reduction in government regulation (as this will make it easier for entrepreneurs to expand their production). The additional wealth created at the top of the income distribution is then expected to ‘trickle down’ to the rest of the population, based on the assumption that the rich will put their additional wealth to good use and re-invest their extra capital in businesses that will generate new jobs for workers, while also paying a good amount of taxes to the government. However, other economists, such as French economist Thomas Piketty, have challenged the validity of the Kuznets curve (Piketty, 2006).

Activity 3: The Kuznets curve in practice

Figure 4 shows the link between economic growth and income inequality estimated by a team around the French economist Thomas Piketty. Describe the relation they found. Does it provide evidence in favour of the Kuznets curve?

Discussion

Piketty and his team found a U-shaped curve rather than an inverted U-shape curve for groups of countries. The empirical observations of him and his team show that inequality across several advanced capitalist societies was high at the beginning of the 20th century, but then slowly decreased to become particularly low during the post-war years. Since the 1980s, income distribution has become more unequal again.

Also other recent studies have come to the conclusion that economic inequality hampers economic growth and is associated with a phenomenon called secular stagnation – slow average economic growth (Shen and Zhao, 2023).This is because economic growth started to ‘stagnate’ from the 1970s onwards across many countries of the Global North, and has been much less stable since then, compared to the period of 1950-1970 (see Figure 5) (Madsen, 2010). Yet, whether or not we can conclude unambiguously that a skewed income distribution has a negative effect on economic growth remains contested.