1 Neoclassical economics: a very brief introduction

The emergence of neoclassical economics is often called the marginalist revolution because of the importance of concepts such as marginal utility or marginal revenue. Jevons (1871) argued that the utility or pleasure we get from an object depends on how many similar objects we already have. Marginal utility often decreases as we get more of a good. Increasing consumption can, beyond a certain point, even decrease our overall utility and well-being. He illustrated this with a famous example about water:

Water, for instance, may be roughly described as the most useful of all substances. A quarter of water per day has the high utility of saving a person from dying in a most distressing manner. Several gallons a day may possess much utility for such purposes as cooking and washing; but after an adequate supply is secured for these uses, any additional quantity is a matter of indifference. All that we can say, then, is, that water, up to a certain quantity, is indispensable; that further quantities will have various degrees of utility; but that beyond a certain point the utility appears to cease.

(Jevons, 1871, pp. 52–53)

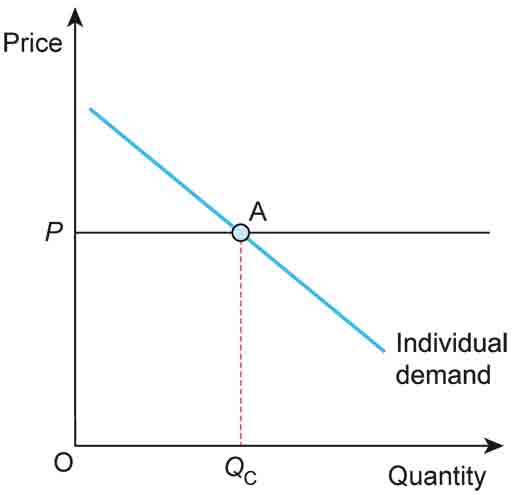

In neoclassical models explaining the behaviour of single agents, such as a firm or a consumer, the main assumption is that they make choices by comparing marginal benefits with marginal costs. So, for instance, to find out a consumer’s demand for a good or service, we compare the additional utility they get from an extra unit with how much this additional unit would cost them, its price. In a diagram, this would look like Figure 2.

Returning to Jevons’ description of the additional benefit of an extra unit as the amount already held increases: the marginal benefit is decreasing as quantity increases. So if price is constant and provided by the market, outside the consumer’s control, the optimal individual demand for a good or service is decreasing too, reflecting the decreasing marginal utility. You can interpret the Individual demand curve as both the consumer’s demand at different prices and as the consumer’s marginal benefit from an extra unit, which determines the price they are willing to pay for it.

Activity 1: Interpreting the individual demand curve

Let’s try to do the same for a firm when market price is beyond its control. This happens in a neoclassical model called perfect competition.

Assuming firms operate in the short run where at least one input to production is fixed, which means that the cost of the other inputs or factors of production rises as more are deployed, sketch a diagram of a firm’s supply curve where optimal quantity produced is set where marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

Hints:

- The firm being a price taker in a perfectly competitive market means the marginal revenue from each product is the market price.

- Assume that the marginal cost, the cost of making an additional unit, rises as more is produced. (In the short run, not all inputs of production can change, and there is no possibility to incorporate gains from innovation and technological progress.)

Comment

Figure 3 shows a firm’s supply in a competitive market where it is a price taker and must supply its output at the market price. Apart from an initial range of output in which increasing production improves efficiency and, therefore, marginal cost falls, the firm’s marginal cost curve is upward sloping. The horizontal line at price P also represents the marginal revenue curve, This is also the firm’s average revenue, as the price doesn’t change when it raises or lowers output.

The firm maximises profit at point B, producing quantity QF. If production is below QF, price (the firm’s marginal revenue in perfect competition) is higher than marginal cost, so the firm can earn more profit by expanding production until marginal cost and marginal revenue (price) are equal. If production is above QF, price is lower than marginal cost, and the firm incurs a loss for the last unit produced; so it should reduce production until marginal cost and marginal revenue (price) are equal. The marginal cost curve is also the firm’s supply curve when operating in perfect competition.

While this activity used a short run model of the firm, the long run model would be very similar. Even though in the long run all inputs of production can change, the most common assumption is that marginal costs increase, and increase by more the higher the quantity due to physical and mental limits of machines, workers, and inputs in general.