5 Dynamic efficiency and competition

So far, we have analysed the economy through a static snapshot. But as you might have noticed from real life, firms have more to decide than price and quantity. To analyse this level of complexity, economists think about dynamic efficiency. Firms analysed through dynamic efficiency focus on innovation and change as they strive to improve their processes or products through research and development (R&D) or by adopting new technology. This means that firms create new products, improve existing ones, develop more efficient production methods or embrace technology to increase their competitive advantage.

Innovation is important for economies as it allows markets to change and adapt to the changing population. R&D investment lets firms adapt to market changes, consumer preferences and competitive pressures. It also encourages new firms to enter the markets, as it creates spaces for new innovative firms to develop while older firms exit the market.

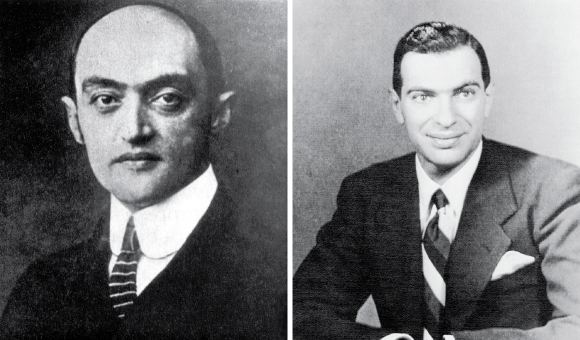

As with other topics, economists have different points of view on how competition affects innovation. Joseph Schumpeter and Kenneth Arrow are the main headliners on this debate, where they try to explain competition and innovation. Welfare economics bases part of its dynamic analysis on the ideas of Kenneth Arrow. At the same time, both the evolutionary and institutional schools of thought use Schumpeter’s ideas.

Kenneth Arrow (1921-2017) explains how a firm in a monopoly does not have any encouragement to innovate and will maintain the same technology (Arrow, 1962). Arrow’s model found that a firm in a monopoly will have a greater risk than a firm in perfect competition. The monopolist has been able to profit from the old technology therefore investing in the new one would be riskier. For the firm in perfect competition, however, its lack of profit makes it more willing to invest in the technology as it can earn more.

In contrast, Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) explained how in a competitive capitalist economy the firm with higher market power will be the one to innovate as it will have better resources to sustain it (Schumpeter, 1942). Because of this assumption, he argues that perfect competition is not the best way for an economy to develop. Firms in perfect competition cannot invest in innovation as all their revenue is spent on the costs of production, even when maximising their profit. Instead it is firms that are shielded from competition, making some additional profit, that have the resources to invest in innovation. They also have the incentive to innovate - to earn temporary monopoly profits. These continue until another firm innovates and makes the previous innovations obsolete. Schumpeter labelled this process “creative destruction”, and saw it as the real source of dynamism in market-driven economies.

The debate on whether perfect competition, monopolies or oligopolies are better to incentivise technology bears directly on how much regulatory intervention a competition policy requires. Thus far, the balance of this debate moves towards Arrow as most Competition Policy enforcers maintain the necessity of competition to incentivise innovation. In the case of the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA 2023) states how competitive markets incentivise competition while monopolies dull this need to innovate.

However, in the model, Arrow mentions the need for firms to protect their innovations to profit and therefore incentivise their development. He mentions how if the firm is unable to benefit from the increased innovation without someone copying their incentive will decrease as the risk is too high. For firms in competition, intellectual property protection is an important incentive to create knowledge as it grants their ability to profit from an invention for a certain time. Nonetheless, it has also created the possibility for firms to abuse their dominance by withholding knowledge.