4.1 Arnstein’s ladder of participation

One much-cited approach to understanding empowerment is Arnstein’s ladder of participation (Arnstein, 1969), which highlights the different forms that empowerment can take. Although originally designed to describe a wider form of participation than empowering service users in organisations, it can still be applied in this context. Box 1 contains an extract from an article in which Arnstein describes how the ladder of participation works.

Box 1 Extract from ‘A ladder of participation in the USA’ by S. Arnstein

2 Types of participation and “nonparticipation”

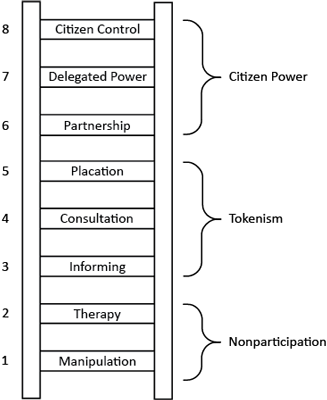

A typology of eight levels of participation may help in analysis of this confused issue. For illustrative purposes the eight types are arranged in a ladder pattern with each rung corresponding to the extent of citizens’ power in determining the end product. (See Figure 2.)

The bottom rungs of the ladder are (1) Manipulation and (2) Therapy. These two rungs describe levels of “non-participation” that have been contrived by some to substitute for genuine participation. Their real objective is not to enable people to participate in planning or conducting programs, but to enable powerholders to “educate” or “cure” the participants. Rungs 3 and 4 progress to levels of “tokenism” that allow the have-nots to hear and to have a voice: (3) Informing and (4) Consultation. When they are proffered by powerholders as the total extent of participation, citizens may indeed hear and be heard. But under these conditions they lack the power to insure that their views will be heeded by the powerful. When participation is restricted to these levels, there is no follow-through, no “muscle,” hence no assurance of changing the status quo. Rung (5) Placation is simply a higher level tokenism because the ground rules allow have-nots to advise, but retain for the powerholders the continued right to decide.

Further up the ladder are levels of citizen power with increasing degrees of decision-making clout. Citizens can enter into a (6) Partnership that enables them to negotiate and engage in trade-offs with traditional power holders. At the topmost rungs, (7) Delegated Power and (8) Citizen Control, have-not citizens obtain the majority of decision-making seats, or full managerial power.

Obviously, the eight-rung ladder is a simplification, but it helps to illustrate the point that so many have missed – that there are significant gradations of citizen participation. Knowing these gradations makes it possible to cut through the hyperbole to understand the increasingly strident demands for participation from the have-nots as well as the gamut of confusing responses from the powerholders.

Though the typology uses examples from federal programs such as urban renewal, anti-poverty, and Model Cities, it could just as easily be illustrated in the church, currently facing demands for power from priests and laymen who seek to change its mission; colleges and universities which in some cases have become literal battlegrounds over the issue of student power; or public schools, city halls, and police departments (or big business which is likely to be next on the expanding list of targets). The underlying issues are essentially the same – “nobodies” in several arenas are trying to become “somebodies” with enough power to make the target institutions responsive to their views, aspirations, and needs.

2.1. Limitations of the Typology

The ladder juxtaposes powerless citizens with the powerful in order to highlight the fundamental divisions between them. In actuality, neither the have-nots nor the powerholders are homogeneous blocs. Each group encompasses a host of divergent points of view, significant cleavages, competing vested interests, and splintered subgroups. The justification for using such simplistic abstractions is that in most cases the have-nots really do perceive the powerful as a monolithic “system,” and powerholders actually do view the have-nots as a sea of “those people,” with little comprehension of the class and caste differences among them.

It should be noted that the typology does not include an analysis of the most significant roadblocks to achieving genuine levels of participation. These roadblocks lie on both sides of the simplistic fence. On the powerholders’ side, they include racism, paternalism, and resistance to power redistribution. On the have-nots’ side, they include inadequacies of the poor community’s political socioeconomic infrastructure and knowledge-base, plus difficulties of organizing a representative and accountable citizens’ group in the face of futility, alienation, and distrust.

Another caution about the eight separate rungs on the ladder: In the real world of people and programs, there might be 150 rungs with less sharp and “pure” distinctions among them. Furthermore, some of the characteristics used to illustrate each of the eight types might be applicable to other rungs. For example, employment of the have-nots in a program or on a planning staff could occur at any of the eight rungs and could represent either a legitimate or illegitimate characteristic of citizen participation. Depending on their motives, powerholders can hire poor people to co-opt them, to placate them, or to utilize the have-nots’ special skills and insights. Some mayors, in private, actually boast of their strategy in hiring militant black leaders to muzzle them while destroying their credibility in the black community.

Activity 6 Ladder of participation

Bearing in mind what you have just read about Arnstein’s ladder of participation, make notes on how this relates to the ‘methods’ of empowerment used by an organisation you are familiar with and how useful you found the model.

Comment

The ladder is, of course, a relatively straightforward framework for understanding empowerment and participation but it can be a useful starting point for thinking about how your organisation works with service users. One useful distinction to consider is between passive and active methods of involvement rather than a linear/ladder model. Methods such as attendance at meetings, consultation, monitoring, evaluation and so on are often regarded as ‘passive’ and may not lead to full empowerment. However, much depends on whether or not the consultee, for example, makes a contribution to meetings. Furthermore, if the consultee makes comments that are not acted upon, this is also not passive.